When firms get together: The secret of success

- Published

How can chief executives ensure a deal is successful?

When two people decide to get married, they vow to stick together - "for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer".

Basically, as those vows acknowledge, marriage is tough and it takes two to make a partnership work. When it comes to company mergers it's no different.

At the moment there's lots of activity in this area. US drugs giant Pfizer is currently trying to buy AstraZeneca, while French engineering company Alstom is attracting interest from both Siemens and General Electric (GE).

So what's the secret to a successful merger?

When UK fund manager Newton bought its smaller rival Capital House from RBS in 1995, the experience was so bad it almost led to divorce.

Capital House had a different culture, a different way of investing and different views on how to add value for clients. All this led to clashes between the two firms.

While the deal was ultimately successful, the difficulty of assimilating it into the group made Newton determined that in the future it would focus on growing its existing operations, rather than making any further acquisitions.

"It was a good experience to learn that at that stage, and that we'd just rather go the slow, maybe slightly longer-term, route," says chief executive Helena Morrissey.

While Ms Morrissey admits she is "very one-sided" - and mergers in the fund management industry are particularly tricky because each firm typically has its own strong investment philosophy - her experience is not unusual.

EBay sold Skype just four years after buying it

Many mergers are not profitable, and corporate history is littered with high-profile failures.

In 2007, German carmaker Daimler had to sell off a majority stake in US firm Chrysler, external, which it had merged with almost 10 years earlier, after losses of billions of dollars.

Similarly, in 2005 eBay paid $2.6bn (£1.4bn at the time) for Skype, external, only to sell it four years later for around $2bn, external saying it had "limited synergies" with the internet phone firm.

"In deals and mergers, there's an 80-20 rule - 80% don't work, 20% are spectacular successes," says leadership expert Steve Tappin.

But when it comes to corporate marriage, there's more than one way to say "I do".

Alliance Unichem merged with High Street chain Boots in 2006

Stefano Pessina, executive chairman of giant pharmacy chain and drugs wholesaler Alliance Boots, has steered the firm through several deals.

He led the 2006 merger of Alliance Unichem with High Street chain Boots, external, and was at the helm in 2012 when US drug chain Walgreens bought a 45% stake in Alliance Boots.

Mr Pessina says successful mergers depend on a long courtship and not rushing the relationship.

For example, in 2015 Walgreens will have the right to buy the rest of Alliance Boots, three years after the initial deal was struck, giving the executives and employees from both firms time to get used to working together.

"A merger is always a shock for the companies. If you have some time, you have the time to develop certain synergies and show that the merger is the right thing to do. When you arrive at the final step the merger is already being consumed," he says.

Assuming a firm has found the right partner, which already shares similar values and is willing to give up its own individual culture to create a shared one, Mr Pessina believes that acquisitions or mergers will create more value than a stock exchange flotation.

Stefano Pessina says mergers provide a platform for growth

Throughout his career, Mr Pessina has sought to grow by merging with larger firms.

Alliance Unichem itself was a result of a merger, between the pharmaceutical wholesale group he'd inherited from his father and rival firm Unichem.

"The other company which is bigger can leverage what we have done and so we create value. Having a wider platform we can see other opportunities, other services and so we start the cycle again."

But securing the right partner is just one part of the equation. Once a deal has been struck, a chief executive has to act decisively and quickly to ensure its success, says former Diageo chief executive Paul Walsh.

The global drinks firm has grown rapidly via acquisitions, including some big ones under his leadership such as wine and spirits brand Seagram, and Mr Walsh says the experience has taught him that in the corporate world there is no such thing as a honeymoon.

"When you acquire something, you take control. You've got a very clear view, because you've been analysing the assets on where the value drivers will be. Prosecute them with rigour."

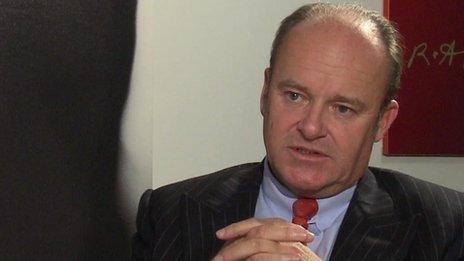

Paul Walsh says firms should change staff rapidly if they don't fit

Mr Walsh advises changing staff rapidly if they do not fit with the firm's aims on how to drive the business forward, and also believes the acquirer bringing in its own finance team always pays off.

But mergers are not always the right way for a company to grow. Mr Walsh says a lot of Diageo's acquisitions were driven by its desire to get particular brands, or access new distribution networks for its drinks. In cases where it felt it was better to build its own brand, it did so, despite it taking longer.

"It does take more patience, but as long as your investors understand the impact that's fine," he says.

As in marriage, it's best to know why you're getting together in the first place, and it lessens the risk of a high-profile divorce.

This feature is based on interviews by leadership expert Steve Tappin for the BBC's CEO Guru series, produced by Neil Koenig and Evy Barry.

- Published29 April 2014