Tax avoidance: What are the rules?

- Published

The case has left many people wondering how to avoid tax avoidance

Gary Barlow and some of his band members will now have a very large tax bill dropping through their letter boxes.

But as far as the law is concerned, they have not done anything wrong in a criminal sense.

Yet even though tax avoidance is normally legal, it can quite easily turn into tax evasion.

And tax evasion - a deliberate plan to cheat the taxman - is most definitely an offence.

So what is the difference between avoidance and evasion, and how can you still go wrong with avoidance?

While the judge in this case took 147 pages to explain what these men had done wrong, there are some simple rules to follow.

Avoidance

Of course everyone is allowed to avoid paying tax if they possibly can. It is perfectly legitimate - indeed the government encourages us - to save in a tax-free Individual Savings Account (Isa), for example.

That means you do not pay any income tax on the interest you receive, or capital gains tax when you come to sell.

There are also tax-saving advantages to putting money into a pension scheme, donating to charity via the gift aid scheme, or claiming capital allowances on things used for business purposes.

But tax reliefs and rules are open to abuse.

"Tax avoidance is bending the rules of the tax system to gain a tax advantage that Parliament never intended," said a spokesman for Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs (HMRC).

"It often involves contrived, artificial transactions that serve little or no purpose other than to produce a tax advantage. It involves operating within the letter - but not the spirit - of the law," he said.

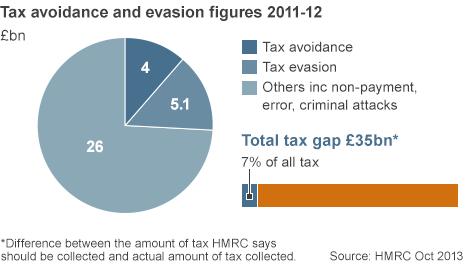

Tax avoidance currently costs the taxpayer £4bn a year, according to the latest figures from HMRC.

That is very nearly as much as illegal tax evasion, which costs £5.1bn.

Together, they account for about a quarter of the £35bn that is lost to the Treasury every year, otherwise known as the "tax gap".

Aggressive

In typical cases, those involved in tax avoidance will pay others to help minimise their tax bills.

If HMRC disagrees with your tax return, you can take them to a tax tribunal, as happened in Gary Barlow's case.

But the judge rejected his claim that the business was making actual losses.

In essence, the court will be looking to decide whether there is any real business going on in such cases, or whether the business is just a means to make a loss, and so reduce a tax bill.

"Don't be taken in by someone trying to interest you in a tax avoidance scheme which promises a result that sounds too good to be true," advises HMRC.

If you do get involved in such "aggressive" tax avoidance schemes, you may end up in a protracted dispute with HMRC, and if you lose, you risk having to pay the tax, the interest and penalties as well.

In some cases, avoidance can quickly turn into evasion.

If you conceal facts, or lie about them, you can be judged to be breaking the law, which could result in a fine, or even a prison sentence.

Rules

To help taxpayers, HMRC advises UK residents to look out for the following warning signs:

it sounds too good to be true and cannot have been intended when Parliament made the relevant tax law (for example, some schemes promise to get rid of your tax liability for little or no real cost, and without you having to do much more than pay the promoter and sign some papers)

the tax benefits or returns are out of proportion to any real economic activity, expense or investment risk

the scheme involves arrangements which seem very complex, given what you want to do

the scheme involves artificial or contrived arrangements

the scheme involves money going around in a circle, back to where it started

the scheme promoter either provides any funding needed to make the scheme work or arranges for it to be made available by another party

offshore companies or trusts are involved for no sound commercial reason

a tax haven or banking secrecy country is involved

the scheme contains exit arrangements designed to side-step tax consequences

there are secrecy or confidentiality agreements

upfront fees are payable or the arrangement is on a "no win, no fee" basis

the scheme has been allocated a Scheme Reference Number (SRN) by HMRC under the Disclosure of Tax Avoidance Schemes (DOTAS) regime.