Business jargon: Squaring the circle

- Published

- comments

"Cost efficiency savings" sounds more positive than "sacking people to save money"

"Putting together the pipelines," was how Pfizer chief executive Ian Read explained his proposed takeover of British drugmaking rival AstraZeneca.

"Let's make sure we get good capital allocation... build a culture of ownership... flexible use of financial assets... productive science... opportunity to domicile... putting together the headcount," were among his phrases as he faced MPs last month, much to the frustration of committee members.

"I asked a simple question," committee chairman Adrian Bailey said at one point.

Use of jargon is not a new phenomenon, but businesses are leaving their customers and even their own staff scratching their heads about where their firms are going and where they themselves stand.

"This jargon is tribal and reinforces belonging," says Alan Stevens, director of Vector Consultants, which advises companies on culture. "It's part of the psyche. But it's not useful."

The current buzzword is "alignment", which Mr Stevens admits he uses too. It describes looking at things from the customer's perspective, which ironically would involve using a lot less jargon, because it is introspective and alienates people, he says.

Pfizer boss Ian Read questioned by MPs on its AstraZeneca bid

Another reason for the rise of business-speak is its defensive qualities.

"We sometimes use jargon to avoid dealing with problems head on," says Prof Joe Nellis, director of Cranfield School of Management.

But is it a problem? Yes, says Rory Sutherland, vice-chairman of advertising agency Ogilvy and Mather UK.

"It's become uglier and uglier," he says.

Some technical terms are difficult to replace, he adds. But the danger emerges when a fashionable word becomes an uncontested good.

The word "downsizing" made swapping a large, expensive house for a small, cheaper one easier to stomach

Sometimes this can work well: "downsizing" made it normal for those with expensive mortgages to move to a smaller home. There was a word for it, so conceiving of it became easier.

But an example of the less useful, says Mr Sutherland, is the proliferation of the words "outsourcing" and "offshoring". That is, sending jobs overseas, where workers are often cheaper.

Its overuse is shown by a trend now for the reverse: "onshoring". Jobs in call centres are returning to the UK because sending them abroad didn't work.

Where businesses wanted to save money, offshoring became the norm, and people were less prone to question it because of its fashionable business jargon status.

What was ignored was the fact that sacking experienced staff and hiring fresh faces with no experience of the company has a cost of its own. So as well as being jarring, these words can be destructive.

"If employees don't get better with time then you are doing something very banal," Mr Sutherland says.

Military language used by economists has crept into business-speak

Another problem is a word or phrase without a definition.

"Market advantage," says Davide Sola, associate professor of strategy at ESCP Europe Business School. "Is it having a bigger market share? Having the ability to charge a premium price? Access to more markets across the globe?"

Everyone may use the phrase for their own purpose, he says.

A lot of jargon in economics has been borrowed from the military, says Prof Nellis. Words and phrases like campaign, rally the troops, follow the leader, keep your powder dry, even recruitment.

The problem, though, is military language is not designed to brook dissent or new ideas, but for obedience.

The military itself isn't immune. BBC journalist Alistair Cooke, broadcaster of Letter from America, remembered a choice phrase from World War Two, during a meeting of commanders in General Eisenhower's headquarters in London.

An American colonel said: "How many ICPs have been counted?"

"What," asked Winston Churchill, "are ICPs?"

"Impaired combatant personnel, sir."

"Never let me hear that detestable phrase again. If you're talking about British troops, you will refer to them as wounded soldiers."

Alistair Cooke concluded: "Muddy language proceeds from muddy minds."

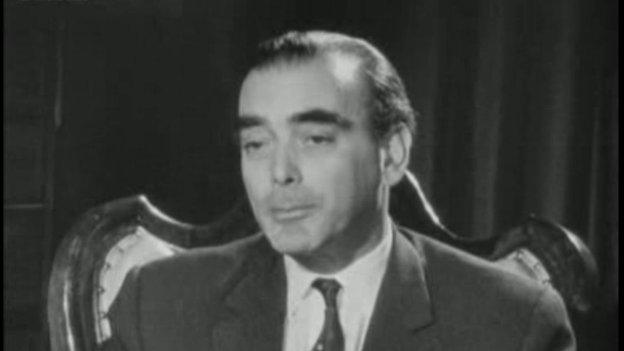

Winston Churchill found certain jargon "detestable"

But perceptions may have changed over time.

Consider this BBC documentary from 50 years ago, where various leaders were interviewed from the most bumf-ridden business of all, finance.

The narrator complains: "Some of the wizards of finance are suave, consultant gentlemen. Some of them have the air of astrologers. Many of them talk a private language."

But jargon in the programme itself is hard to find.

AG Ellinger, an investment adviser, explains his use of charts to predict stock price performance: "People think stocks and shares go up and down because of obscure reasons about companies. They really go up and down because people buy and sell them."

Nicholas Stacey, chairman of Chesham Amalgamations and Investments, talks about the advice he gives to businesses planning to merge.

"Even after we have put in anything like six, or seven, or nine months' work, sometimes all our efforts and all our diplomacy and all our knowledge has been for nowt," he says, "for the very simple reason that at the final clinch at the negotiation, something, somehow goes wrong."

Would a banker today say something like that?

Nine months' advice can be "for nowt", says the candid Nicholas Stacey

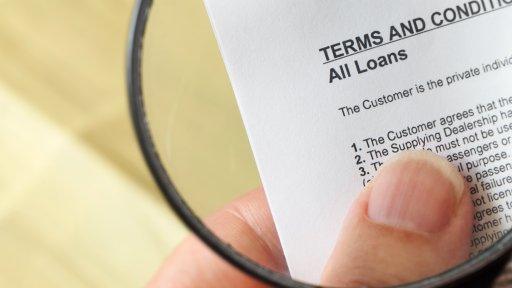

Part of the backlash from business watchers, including investors and regulators, is due to more study of what this jargon means, says David Larcker, accounting professor at Stanford Business School.

"The linguistic patterns for business communication are fascinating," he says. Nearly every business conference call held with market analysts and investors is now transcribed and is searchable, he says. They can be put in a computer, analysed and tested.

"The media is more brutal than before," adds Richard Hytner, deputy chairman of Saatchi and Saatchi. "People are watching every word spoken."

Business leaders such as Pfizer's Mr Read need to drop jargon quickly or risk making it a permanent fixture, says Steve Jenner, spokesman for the Plain English Campaign.

"If everyone in that company is used to this sort of nonsense being bandied about by management, they soon get the idea that this is the key to advancement within the company.

"And so business jargon becomes self-perpetuating and its use can accelerate alarmingly until some brave person stands up and says: 'This is nonsense. Stop it.'"

- Published13 January 2014

- Published19 May 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published16 April 2014