The importance of early cancer diagnosis

- Published

- comments

Lung cancer gets a relatively smaller share of research funding

I am doing something slightly different from my normal routine later today, and something a bit uncomfortable, which is that I am chairing a session at a conference on "National Cancer Outcomes", organised by the National Cancer Intelligence Network, external.

And before that, at 12:15, I will be on Shelagh Fogarty's 5 Live show, interviewing experts on why mortality rates for cancer sufferers are higher in the UK than for comparable rich countries - and how to improve sufferers' life expectancy by diagnosing cancers much earlier.

You may be aware that this is an issue of considerable importance to me, because my darling wife, the writer Sian Busby, died of lung cancer in September 2012.

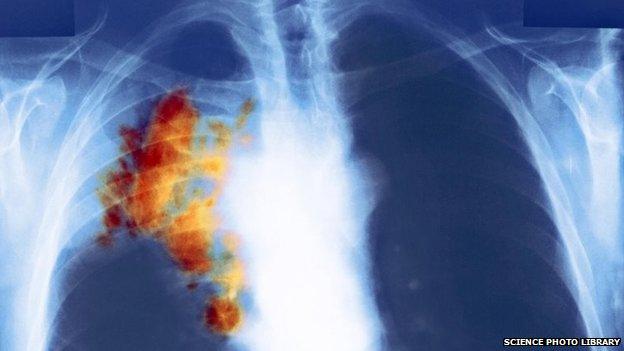

One of the issues in cancer care I have subsequently been highlighting has been the relatively small resources devoted to research into lung cancer - which is by far the biggest cancer killer, and is a massive killer not only of smokers but of lifelong non-smokers like Sian.

Here is something I wrote last year about the apparent underfunding of research.

Catch it early

My concern was, and is, that there is a general and insidious prejudice against lung cancer sufferers, that leads to underfunding of research, based on the idea that somehow they have brought it on themselves by smoking.

And as a result, the breakthroughs we are seeing in genetic-based research, which is generating drugs that are significantly extending lives of other cancer sufferers, may be arriving slower in lung cancer.

That said, the best way to treat lung cancer - and indeed many cancers - is to cut it out early, when it is still small, before the malignant cells have the opportunity to spread.

Surgeons are still life savers for many cancers, but they are most effective when what they need to remove is contained.

So spotting the disease early really matters.

Surgery

In the case of Sian, I do periodically have to fight back my frustration that Sian was not X-rayed in March of 2007, when she went to an NHS walk-in clinic struggling to breathe. The clinic put her on a nebuliser, to open her airways, without apparently wondering why an apparently fit and healthy 46-year-old woman should be wheezing so badly.

It would be three months before she returned to our GP, still feeling under the weather and complaining of a pain in her back. He then very sensibly sent her to be X-rayed in our local hospital.

Only 11% of lung cancer patients who were diagnosed during an emergency were alive after 12 months

And thank goodness he did. Because as a result of the surgery that followed, Sian lived for another five years - wonderful precious time for which I will always be profoundly grateful.

Even so, although our brilliant surgeon removed most of the cancer, he didn't get all of it. Which is why my unbelievably courageous wife had years of hideous treatment as the cancer spread - to her brain initially, then to spine and liver (though as I've said before, Sian was never disheartened, and lived on the basis that she would get better).

GP luck

For the avoidance of doubt, those five years of life meant Sian beat the odds - because only 35.4% of women in England live a year after being diagnosed with lung cancer, according to the latest official statistics (and the survival rate is just 31% for men).

But I find it hard to suppress the heartbreaking notion that Sian could still be alive today, if she had been diagnosed those few months earlier.

On the other hand, I also recognise that Sian was lucky to have such an astute GP who sent her off for tests.

New research by the National Clinical Intelligence Network and Public Health England show that only 11% of lung cancer patients who were diagnosed when they were so ill that they were classified as an emergency - so the diagnosis was usually in a hospital's A & E unit - were alive after 12 months.

Slow improvement

And what is tragic - and perhaps scandalous - is that 38% of all diagnoses were such an emergency.

Here is the big point: when GPs initiate the diagnosis before the patient is suffering extreme symptoms, the 12-month survival rate rises very markedly, to 38%.

Now for all cancers, 22% of cancers were diagnosed in an emergency setting from 2006-2010, a very small improvement on the previous four years.

But many would probably say the improvement was not fast enough, given the link between catching the cancer early and survival.

And compared with some other rich countries, the UK is relatively poor at early diagnosis - which of courses is grounds for optimism that the NHS can do better.

Non-smokers

I hope to learn more about what is being done to improve diagnosis in the course of the day.

But the big explanations for why we can do better appear to be - for lung cancer in particular - that it is not always easy to spot the symptoms, that there is ignorance about the symptoms among public and also among GPS, that even among medical professionals there is not enough awareness of the prevalence of lung cancer among non-smokers, and the head-in-sand factor, or horrible sweat-inducing fear.

One reason why so many people don't have a health check for possible lung cancer, for example, is that they fear the cancer is always a death sentence and so they don't want to know about it, especially if they smoke.

But if it is identified early enough, even lung cancer does not have to be the end.