Dublin's housing boom fuels surge in homelessness

- Published

Dublin is undergoing a simultaneous increase in homelessness and a mini property boom. It might seem a contradiction but at the heart of both is Ireland's economic crash of 2008, from which the country is still trying to recover.

Rising homelessness and property prices have been driven by a housing shortage for a young and growing population. Building virtually stopped in Ireland's crash of six years ago, and austerity has meant a slump in state-funded housebuilding as well as social welfare cuts.

The shortage of accommodation has seen Dublin rents rise - meaning investors are now buying up property, driving the mini-boom.

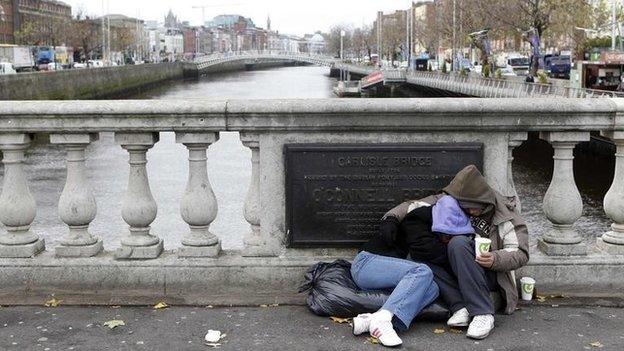

About 2,700 people are officially homeless in Ireland. The state provides emergency accommodation but some - a minority - end up sleeping on the streets. Charity is a lifeline for many.

The number of people coming through the doors of the Capuchin Day Centre in the centre of Dublin is up six-fold. Volunteers and staff serve free meals to anyone in need.

"Ten years ago it was around 160 meals a day - now it's 600," says one of the chefs. "People have no idea, until they come in here, to see the children coming in here in their school uniforms, they go home with nothing to eat until the next day sometimes.

"But now they are looking after them here and they give them a goody bag going home."

Protesters have called for swift action to be taken on homebuilding

'Closest thing to prison'

Many of these people had never expected to become homeless, says Angela Skuce, a doctor working in the centre.

"A lot of them are entitled to rent allowance as part of their benefits but rents in Dublin have gone up so their rent allowance doesn't pay for that."

Lynn Claxton dines with her four children - a break from their small, single room in emergency accommodation.

"I've never been to Mountjoy Jail but as far as I can see it's the closest thing to prison. The children can't go outside the room and can't play," she says.

"I never thought in my wildest dreams that I'd end up in this situation like the other people here. They're normal everyday people that are trying to make ends meet, with nowhere to go - people with children just trying to survive."

'Unprecedented' demand

Many landlords now prefer to take higher cash rents from private tenants, instead of the rent allowance offered by those on benefits.

Another young woman at the table says soaring rents made her family of four recently homeless for the first time, despite being able to offer 950 euros (£760) a month for rent.

But the high rents have been driving a mini property boom with investors flocking to Dublin, says Robert Hoban of Allsop Space auctioneers.

"There's unprecedented demand for suburban family homes, for young couples to buy, to grow families in. Not enough properties have been constructed," he says.

"What's selling very, very well are tenanted commercial properties - almost of any size - anything with income at the moment, there's a lot of interest from investors because they see it as a long-term investment."

Property consultant Colin Horan sees plenty of demand for Dublin property from Russian buyers

Property prices in Dublin in April were 18% higher than a year ago, according to the Central Statistics Office.

While Irish citizens still make up the majority of buyers, Colin Horan of Extra Sales property consultants says Russian, Chinese, American, British and European investors are also in competition. His firm even has Russian-speaking staff to help buyers from the east.

"There are two different types of Russians buying - one is the very wealthy Russian, then there's average Russians buying second homes here in Ireland as well for investment.

"It is [also] very buoyant from the Chinese perspective. Even the auctions that are happening in Dublin - there are major investors at those and they are bringing the prices up. The type of properties they're buying is like family homes that are from 400,000 euros up to one million," he says.

Ghost estates

Ireland's Housing Minister, Jan O'Sullivan, has unveiled plans to restart some building and restore disused state properties.

These houses in North County Dublin have been sold before they are even finished

But what of Ireland's so-called ghost estates - empty houses from the boom?

Many are in remote areas far from Dublin and its hinterland where about a third of Ireland's population live, so the empty houses remain far from the people needing a roof over their heads. Ms O'Sullivan says there is no easy match.

"There is an element of a solution in those unfinished estates but the quantity really is not huge. But we will identify those that we can use and have identified a number already.

"They are part of the solution but some of them are in places where there isn't a housing demand so they are not suitable in some cases for social housing. But there are others in the greater Dublin area and around our cities that will be suitable," she says.

Homeless capital of Europe?

Meanwhile, the homeless have taken to Dublin's streets to protest against their plight, which has hit the headlines here.

Many have been seeking to raise awareness of the plight of the homeless

Jesuit priest Father Peter McVerry, who has been a champion of Dublin's homeless, says it is the worst housing crisis in his 40 years working with the city's poorest - but he fears greater disaster ahead.

"We need urgently to get back to building social housing. That's expensive but if we don't do it, we are going to have a city here full of homeless people and homeless families living on the street.

"We've 100,000 households on the social housing waiting list. Five thousand social houses every year would cost one billion euros - we don't have one billion euros to spend on housing over the next 20 years. The failure to do that will make us the homeless capital of Europe," he warns.

Ireland has been praised by its international lenders for following the course of austerity medicine. But for those without a place to live, there is little feeling of economic recovery.

For more on this story, listen to Diarmaid Fleming's report on the The World Tonight on BBC Radio Four.

- Published28 November 2013

- Published27 November 2013

- Published12 December 2013