Eurozone crisis: Ireland breaks free

- Published

- comments

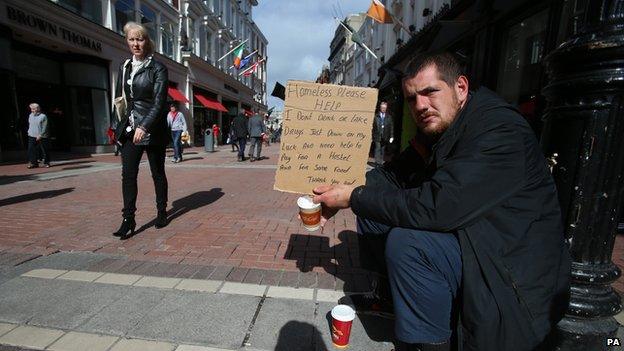

Austerity has caused more hardship, even though the economy has returned to growth

This weekend marks an important milestone for the eurozone. The Republic of Ireland, the second European country to need bailing out, will leave the programme - exiting financial rehab.

There will be no safety net; Ireland will gradually fund itself from the markets. "We are confident we are making a clean exit." says Finance Minister Michael Noonan. "We are not junk. We are doing well."

So Ireland will be the first of the bailed-out countries to step free from its economy being overseen by the troika - the European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund.

There will be quiet satisfaction in the corridors of Brussels and Berlin. They will grasp the moment as providing evidence that the medicine of bailouts, austerity and reforming labour markets can work. In their frequent praise for Ireland they can scarcely disguise their gratitude.

Nation's 'shame'

It is worth recalling the mood in Ireland back in November 2010. The Irish government had rescued reckless banks, taken on their debts, and was struggling to finance itself. Dublin created a "war room" to fight off the humiliation of a bailout. Sunday, 21 November was the reckoning. Ireland accepted an 85bn-euro (£71bn; $117bn) rescue.

With the bailout came a national shudder, with the Irish Times, in its editorial, borrowing a headline from a poem by WB Yeats and asking "Was it for this?" There were many who shared the paper's lament "the shame of it all".

"Having obtained our political independence from Britain to be masters of our own affairs," the lament continued, "we have surrendered our sovereignty to the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund". The Irish finance minister at the time told the BBC that it felt like "hell was at the gates".

That was just over three years ago, but the shamed Celtic Tiger knuckled down. The government cut nearly 30bn euros in spending and raised taxes. Salaries were squeezed by 20% and benefits even for unemployment and disability were reduced.

The country, with its low corporate tax rate, became the hi-tech gateway into Europe for companies like Google, Paypal and Facebook. Gradually Ireland returned to growth. It is expected to hit 1.8% next year. Unemployment, although still at 12.5%, is falling.

Swords, Dublin: Housebuilding is picking up again, in a sector left desolate by the crisis

Social problems

Victory, however, has been bought at some cost.

It is claimed that the poorest have borne the brunt of the cuts. The think-tank Social Justice Ireland claims, external the poorest 10% have lost a fifth of all their income; that is harsher than for other groups in society.

Homelessness has increased by 20% since 2010. In a major survey, Growing up in Ireland, external found that 60% of families were experiencing difficulties in making ends meet - double the number from four years before. And 13% are behind with paying utility bills. A very significant number of homeowners are struggling to pay their mortgages.

And then there is emigration. The writer Fintan O'Toole once said that "mass emigration had always been the index of Ireland's failure". It is back. Last year more than 75,000 left the country. And 200,000 have gone since 2008. Some moved to the UK, but many headed west to Canada and the US as previous generations had done.

Emigration helped disguise the unemployment. Some have even suggested that the government actually encouraged emigration.

Going forward there will have to be another round of cuts and it will take decades to pay back the loans. But investors have rediscovered their faith in Ireland.

It may be that Portugal and eventually Greece will follow Ireland in throwing off the bailout "straitjacket". But for Europe two questions follow: will hundreds of thousands of young people across Europe have to look outside the continent for work? And have the years of austerity weakened Social Europe which, previously, had been one of its defining features?