How many Greek legends were really true?

- Published

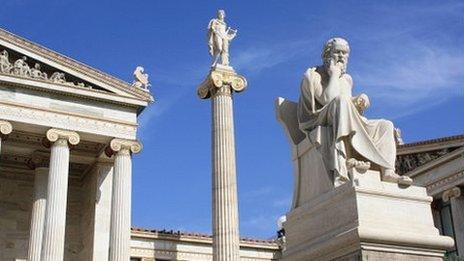

The culture and legends of ancient Greece have a remarkably long legacy in the modern language of education, politics, philosophy, art and science. Classical references from thousands of years ago continue to appear. But what was the origin of some of these ideas?

1. Was there ever really a Trojan Horse?

The story of the Trojan Horse is first mentioned in Homer's Odyssey, an epic song committed to writing around 750BC, describing the aftermath of a war at Troy that purportedly took place around 500 years earlier.

After besieging Troy (modern-day Hisarlik in Turkey) for 10 years without success, the Greek army encamped outside the city walls made as if to sail home, leaving behind them a giant wooden horse as an offering to the goddess Athena.

The Trojans triumphantly dragged the horse within Troy, and when night fell the Greek warriors concealed inside it climbed out and destroyed the city. Archaeological evidence shows that Troy was indeed burned down; but the wooden horse is an imaginative fable, perhaps inspired by the way ancient siege-engines were clothed with damp horse-hides to stop them being set alight by fire-arrows.

.jpg)

2. Homer is one of the great poets of ancient Greek legends. Did he actually exist?

Not only is the Trojan Horse a colourful fiction, the existence of Homer himself has sometimes been doubted. It's generally supposed that the great epics which go under Homer's name, the Iliad and Odyssey, were composed orally, without the aid of writing, some time in the 8th Century BC, the fruit of a tradition of oral minstrelsy stretching back for centuries.

While the ancients had no doubt that Homer was a real bard who composed the monumental epics, nothing certain is known about him. All we do know is that, even if the poems were composed without writing and orally transmitted, at some stage they were written down in Greek, because that is how they have survived.

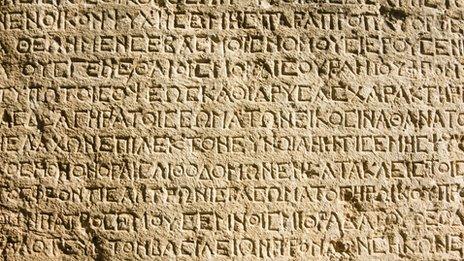

3. Was there an individual inventor of the alphabet?

The date attributed to the writing down of the Homeric epics is connected to the earliest evidence for the existence of Greek script in the 8th Century BC.

The Greeks knew that their alphabet (later borrowed by the Romans to become the western alphabet) was adapted from that of the Phoenicians, a near-eastern nation whose letter-sequence began "aleph bet".

The fact that the adaptation was uniform throughout Greece has suggested that there was a single adapter rather than many. Greek tradition named the adapter Palamedes, which may just mean "clever man of old". Palamedes was also said to have invented counting, currency, and board games.

The Greek letter-shapes came to differ visually from their Phoenician progenitors - with the current geometrical letter-shapes credited to the 6th Century mathematician Pythagoras.

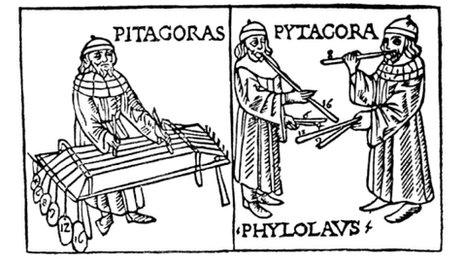

4. Did Pythagoras invent Pythagoras' theorem? Or did he copy his homework from someone else?

It is doubtful whether Pythagoras (c. 570-495BC) was really a mathematician as we understand the word. Schoolchildren still learn his so-called theorem about the square on the hypotenuse (a2+b2 =c2). But the Babylonians knew this equation centuries earlier, and there is no evidence that Pythagoras either discovered or proved it.

In fact, although genuine mathematical investigations were undertaken by later Pythagoreans, the evidence suggests that Pythagoras was a mystic who believed that numbers underlie everything. He worked out, for instance, that perfect musical intervals could be expressed by simple ratios.

5. What made the Greeks begin using money? Was it trade or their "psyche"?

It may seem obvious to us that commercial imperatives would have driven the invention of money. But human beings conducted trade for millennia without coinage, and it's not certain that the first monetised economy in the world arose in ancient Greece simply in order to facilitate such transactions.

The classicist Richard Seaford has argued that the invention of money emerged from deep in the Greek psyche. It is tied to notions of reciprocal exchange and obligation which pervaded their societies; it reflects philosophical distinctions between face-value and intrinsic value; and it is a political instrument, since the state is required to act as guarantor of monetary value.

Financial instruments and institutions - coinage, mints, contracts, banking, credit and debt - were being developed in many Greek cities by the 5th Century BC, with Athens at the forefront. But one ancient state held the notion of money in deep suspicion and resisted its introduction: Sparta.

6. How spartan were the Spartans?

The legendary Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus decreed that the Spartans should use only iron as currency, making it so cumbersome that even a small amount would have to be carried by a yoke of oxen.

This story may be part of the idealisation of the ancient Spartans as a warrior society dedicated to military pre-eminence. While classical Sparta did not mint its own coins, it used foreign silver, and some Spartan leaders were notoriously prone to bribery.

However, laws may have been passed to prevent Spartans importing luxuries that might threaten to undermine their hardiness. When the Athenian playboy general Alcibiades defected to Sparta during its war with Athens in the late 5th Century, he adopted their meagre diet, tough training routines, coarse clothing, and Laconic expressions.

But eventually his passion for all things Spartan extended to the king's wife Timaea, who became pregnant. Alcibiades returned to Athens, whence he had fled eight years earlier to avoid charges of shocking sacrilege, one of which was that he had subjected Athens' holy Mysteries to mockery.

7. What were the secrets of the Greek Mystery Cults?

If I told you, I'd have to kill you. The secrets were fiercely guarded, and severe penalties were prescribed for anyone who divulged them or who, like Alcibiades, were thought to have profaned them. Initiates were required to undergo initiation rites which may have included transvestism and centred on secret objects (perhaps phalluses) and passwords being revealed.

The aim was to give devotees a glimpse of the "other side", so that they could return to their lives blessed in the knowledge that when their turn came to die they could ensure the survival of their soul in the Underworld.

Excavations have uncovered tombs containing passwords and instructions written on thin gold sheets as an aide-memoire for deceased devotees. The principal Greek Mystery Cults were those of Demeter, goddess of agriculture, and of Dionysus (also known as Bacchus), god of wine, ecstasy - and of theatre.

8. Who first made a drama out of a crisis? How did theatres begin?

In 5th Century Athens, theatre was closely connected to the cult of Dionysus, in whose theatre on the southern slopes of the Acropolis tragedies and comedies were staged at an annual festival.

But the origin of theatre is a much-debated issue. One tradition tells of the actor Thespis (hence "thespian") standing on a cart and playing a dramatic role for the first time around 532BC; another claims that drama began with ritual choruses and gradually introduced actors' parts.

Aristotle (384-322BC) supposed that the choruses of tragedy were originally ritual songs (dithyrambs) sung and danced in Dionysus' honour, while comedy emerged out of ribald performances involving model phalluses.

As a god associated with shifting roles and appearances, Dionysus seems an apt choice of god to give rise to drama. But from the earliest extant tragedy, Aeschylus' Persians of 472BC, few surviving tragedies have anything to do with Dionysus.

Comic drama was largely devoted to making fun of contemporary figures - including in several plays (most famously in Aristophanes' Clouds) the philosopher Socrates.

9. What made Socrates think about becoming a philosopher?

Socrates (469-399BC) may have had his head in the clouds, and was portrayed in Aristophanes' comedy as entertaining ideas ranging from the scientifically absurd ("How do you measure a flea's jump?") to the socially subversive ("I can teach anyone to win any argument, even if they're in the wrong").

This picture is at odds with the main sources of biographical data on Socrates, the writings of his pupils Plato and Xenophon. Both the latter treat him with great respect as a moral questioner and guide, but they say almost nothing of Socrates' earlier activities.

In fact our first description of Socrates, dating to his thirties, show him as a man of action. He served in a military campaign in northern Greece in 432BC, and during a brutal battle he saved the life of his beloved young friend Alcibiades. Subsequently he never left Athens, and spent his time trying to get his fellow Athenians to examine their own lives and thoughts.

We might speculate that Socrates had toyed with science and politics in his youth, until a life-and-death experience in battle turned him to devoting the remainder of his life to the search for wisdom and truth.

As he wrote nothing himself, our strongest image of Socrates as a philosopher comes from the dialogues of his devoted pupil Plato, whose own pupil Aristotle was tutor of Alexander, prince of Macedon.

10. Was Alexander the Great really that great?

Alexander (356-323BC) was to become one the greatest soldier-generals the world had ever seen.

According to ancient sources, however, he was physically unprepossessing. Short and stocky, he was a hard drinker with a ruddy complexion, a rasping voice, and an impulsive temper which on one occasion led him to kill his companion Cleitus in a violent rage.

As his years progressed he became paranoid and megalomaniacal. However, in 10 short years from the age of 20 he forged a vast empire stretching from Egypt to India. Never defeated in battle, he made use of innovative siege engines every bit as as effective as the fabled Trojan Horse, and founded 20 cities that bore his name, including Alexandria in Egypt.

His military success was little short of miraculous, and in the eyes of an ancient world devoted to warfare and conquest it was only right to accord him the title of "Great".

Dr Armand D'Angour is associate professor of classics at the University of Oxford