Do quantum computers threaten global encryption systems?

- Published

The modern world is a house of cards built upon encryption.

Make a mobile phone call and encryption is there to stop eavesdroppers listening in.

Spend money online and encryption ensures your card number and identity cannot be scooped up and used elsewhere.

And the money that keeps global banking systems lubricated only does so thanks to cryptographic software that turns a stream of data into unintelligible nonsense.

Remove all that encryption and the whole lot comes tumbling down.

If that happens we might return to an era when commerce was mostly done face-to-face and based around who you know.

Scrambled

Yet quantum computers - another modern marvel - are threatening to make this doomsday scenario a reality.

Why?

"Because of the possibilities for massive parallelism," says Prof Mark Manulis, a cryptographic expert from the University of Surrey's department of computing.

In other words, because of a quantum computer's potential ability to do trillions of calculations a second.

When a message is scrambled with a modern encryption system, the keys used to lock it are typically very large numbers - tens, if not hundreds, of digits long.

Finding that key means using a computer to carry out lots of sums and then trying each answer to see if it unlocks a message an attacker is interested in.

If encryption fails then we might return to a very different type of commerce

The sheer number of possible answers lends protection because it would take centuries, or longer, to find the right key.

Unless large-scale quantum computers are commonplace, says Prof Manulis.

Quantum computers can crank through those sums so fast because their basic building blocks, known as qubits, can be used to represent both a zero and a one at the same time.

By contrast the computational elements, bits, of the classical computers under our desks and on our laps represent either a zero or a one. Not both.

The curious properties of the quantum realm mean that when those qubits work together you get a vast rise in computational power - hence the potential they have to speed things up, find keys and crack codes.

Number crunching

Most significantly affected by the arrival of quantum computers are the public key infrastructure (PKI) systems we use to establish secure channels of communication online.

Typically, when you turn up at a website it is PKI that sets up the initial connection. With that secure channel created, different encryption systems that are much less susceptible to attack by quantum computers are used to protect data shuttling back and forth.

"Public key cryptography is based on problems from number theory, integer factorisation and discrete logarithms, that will be broken once we have powerful quantum computers," said Prof Manulis.

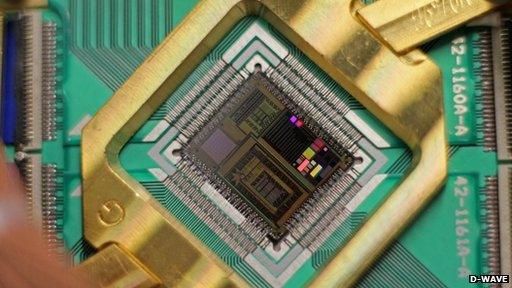

Canadian firm D-Wave sells a working quantum computer

The key word here is "once".

But that once might be a long time coming, believes Dr Stephan Ritter, who studies quantum computers at the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics in Garching, Germany.

"Quantum computers are not very powerful at the moment but they have this potential, and that's what this is about," he told the BBC.

"Experimentally I would say that we are at the stage where it's not even clear which physical elements they will be made of."

Researchers have yet to agree on the best way to build these qubits and how to link them together. So far, Dr Ritter says, only quantum computers with a small handful of qubits have been made - a long way from the hundreds and thousands needed to make it able to do useful work and do it quickly.

"There are proofs of concept of these building blocks but they all have advantages or disadvantages, so it's unclear which will be the best as we go forward," he says.

Controversial

Despite what Dr Ritter sees as a lack of progress, Canadian firm D-Wave will sell you a working quantum computer if you have $15m (£8.9m) to spare.

The way it operates is controversial and its price suggests it will not be the widely available device that can crack all our codes.

Even when they are available, says Dr Ritter, we should not think of them as wonder machines that speed up any and every batch processing job or database search.

US scientists have created a very pure form of silicon-28, an essential component of a quantum computer

"They are good for very specific tasks," he says, "but not everything is faster with a quantum computer and there will be many tasks you will not use one for at all."

As a result we should have a few years yet to update and improve our encryption systems as research and development work on quantum computers continues.

'Badly broken'

That's just as well, says Dr Tanja Lange, a coding theory and cryptology expert from the Technical University of Eindhoven, as it can take a long time for older encryption systems to be swapped out in favour of more secure alternatives.

For instance, she says, it took five to six years to swap out the widely used MD5 data scrambling system once its weakness was demonstrated through a viable attack. Timescales can stretch for systems already used widely in the field, such as those found in cash machines, smart cards and mobile phones.

"However, if a system is absolutely badly broken, roll-out can be faster," she says. "RSA sent new tokens promptly after they had a break-in and credit card companies are used to replacing cards if there is a risk that they were compromised."

Encryption ensures that no-one can listen in to you while you walk and talk

What will be harder, she says, is migrating everyone to the software systems that can resist attack by quantum computer. At the very least such systems require much bigger encryption keys and that means they are much less efficient - for which read, slower.

"We hope that with another three to five years of research we can design systems that are smaller, but we're not there yet," she says.

"Currently we can give you a tank with concrete enforcement - it's secure but big.

"We hope to find a way to give you a secure sports car with airbags, ABS and all that neatly hidden away in a sleek design."