Purer-than-pure silicon solves problem for quantum tech

- Published

The silicon is very hot and glows when it is collected inside a vacuum chamber

In a quantum computer, pure silicon is not enough - only one specific type of silicon atom will do.

The good stuff is silicon-28, and physicists in the US have worked out how to produce it with 40 times greater purity than ever before.

Even better, they can do it in the lab instead of relying on samples made ten years ago in a huge, repurposed plutonium plant in St Petersburg.

This promises to solve a serious supply problem in quantum computing research.

Several of the most promising schemes for building a quantum computer are based in silicon. One that has received much attention stores "qubits" in atoms of another element, like phosphorous, embedded in a tiny layer of ultra-pure silicon-28.

Qubits are the quantum replacement for bits - the ones and zeros that represent information inside a conventional computer. They promise to usher in a new era of computing because they can simultaneously encode a one and a zero, enabling incredibly fast and complex calculations.

The difficulty for silicon-based designs is that normal silicon contains quite a lot of atoms that aren't silicon-28. Almost 8% of a commercial silicon wafer is made up of other isotopes like silicon-29, which would cause interference in a quantum chip.

"It leads to decoherence, which is sort of like ADD in computers," explained Dr Joshua Pomeroy, one of the physicists behind the new work, from the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Maryland.

Researchers in this field, like Dr Pomeroy, have been relying on off-cuts of enriched silicon-28 that all started out in Russia.

The St Petersburg facility is a repurposed plutonium enrichment plant, housing industrial-scale gas centrifuges which were commissioned in 2004, by German scientists, to produce a sample of silicon-28 with 99.99% purity.

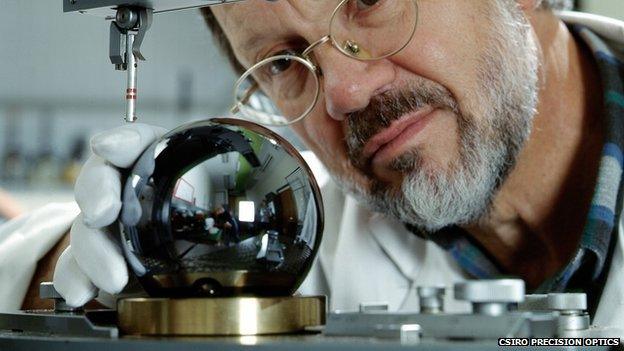

That sample was used to crystallise 5kg of the stuff, at a cost of around one million euros, for an international effort to calculate Avogadro's number, external from 1kg, perfect spheres of silicon-28.

Waste material from this project has been almost the only global source of this high-quality silicon ever since.

Most of the world's purest silicon-28 was used to make perfect 1kg spheres as part of the Avogadro project

Dr Pomeroy explained that the quantum community "can't command the resources" to commission that type of production. "It's fortuitous that the Avogadro project existed," he told the BBC.

"So there's sort of a nervousness - when they wrap up finally, and they're not buying any more of it, what are we going to do?"

But Dr Pomeroy and his colleagues have now shown that small amounts of silicon-28, enriched to an unprecedented 99.9998%, can be produced using equipment already found in many labs.

Small but perfectly formed

They managed the feat with kit that is normally used for mass spectrometry - a technique for identifying a substance based on the weight of the different atoms it contains. By pumping ions of silicon through a big magnetic field, the different isotopes (atoms of silicon with different weights) can be separated from each other, because heavier atoms are diverted less by the magnet than lighter ones.

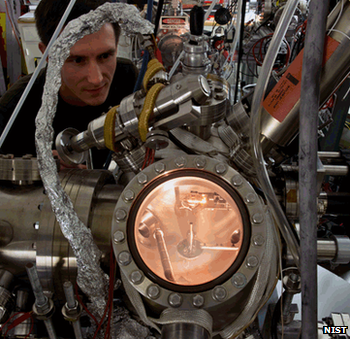

The equipment is normally used in mass spectrometry, which identifies substances based on their molecular weight

Dr Pomeroy said this was an unexpectedly simple solution. "We had what often happens in science, which is that we had an apparatus whose purpose had come to an end. And we had a problem that needed solving, and we married them up."

The thin films of silicon-28 that his team can produce are very, very pure - but also very small.

"It's much more difficult to produce large quantities," Dr Pomeroy concedes, "but particularly in the research phase, those quantities are largely unnecessary."

Despite some controversial commercial initiatives, quantum computers primarily remain a field of research. And according to Dr Pomeroy, the new approach is more than capable of delivering enough of the purer-than-pure silicon for scientists to test out their designs.

Importantly, researchers around the world could potentially make it in their own labs.

"We're recognising that we don't need to produce an entire wafer's worth of silicon-28 that's enriched," he said. "We only really need to make enough to insulate the computer from the rest of the wafer."

The team's research was published in the Journal of Physics D, external.

- Published2 August 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published15 November 2013