Beware the Carney premium

- Published

- comments

Why would it matter that the governor of the Bank of England may be behaving like an "unreliable boyfriend" - in the words of Labour MP Pat McFadden - blowing "one day hot, one day cold" on when interest rates will rise?

If interest rates are bound to go up some time, is there any material economic impact from the different signals from the Bank over the past year, and especially in the past few days, about when the end of almost free money will formally begin?

Just to remind you, last summer the Bank's novel "forward guidance" - tying rate rises to improvements in the labour market - implied no rate rises until 2016.

Then, when it became clear that the Bank's forecast of how fast unemployment would fall was far too pessimistic, expectations of the date of the first rate rise were progressively brought forward to various dates in 2015.

Then forward guidance was modified to become less formulaic and more a judgement about slightly nebulous spare capacity in the economy - on the basis that prices are likely to accelerate when slack in the economy has been exhausted, because businesses would be more likely to respond to increased demand by putting up prices.

And because determining spare capacity is more art than science, the governor's pronouncements on it take on much greater significance. If the data can no longer speak for itself, any interpretations of ambiguous economic evidence by the governor are understandably seen as a broad hint of what the Bank of England plans to do.

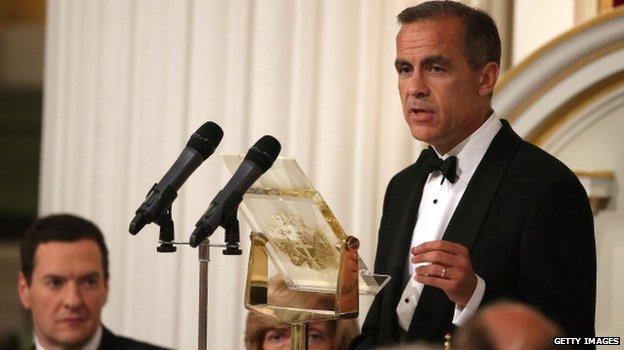

In this oracular incarnation, at the Mansion House last week, the governor nodded to a possible rate rise in the autumn - and as a result sterling rose and the price of financial assets adjusted to discount such an early rise.

But yesterday the tea leaves had apparently changed: Mark Carney seemed to row back again, with remarks suggesting underlying inflationary pressures may yet be too subdued to warrant any kind of rate rise till next year.

The pound fell, and investors started betting again on a rise in interest rates perhaps postponed until next year.

Which probably leaves you feeling a bit confused about when the Bank of England will start to raise the cost of money for the first time since its policy rate or Bank rate was cut to 0.5% in March 2009.

"Who cares?" you might ask.

Surely a bit of uncertainty never did any serious harm - especially since the Bank of England has been consistent in saying that, as and when rates rise, the increases will be small, and that Bank rate over two or three years is unlikely to climb above 3%, thus remaining well below historical norms.

Well I have been talking to bankers and investors who control squillions of pounds and they say the to-ing and fro-ing, the blowing hot and cold in McFadden's words, could come at a cost to the UK.

How so?

Well investors and lenders dislike volatility and unpredictability, they reward predictable borrowers and punish unpredictable borrowers.

And they do this by demanding a higher interest rate, a so-called risk premium, for borrowers who are deemed a bit flaky.

So if Carney were to thoroughly bemuse the markets about the likely path of interest rates, and the yo-yoing of sterling intensified, while the price of interest-rate linked assets also became more volatile, there would be an increase in the risk premium or interest rate paid by anyone borrowing in sterling - including the government.

In other words, if Carney really is an unreliable boyfriend, in respect of monetary policy, then the cost of money for all of us would become more expensive - and that would have a deleterious effect on growth and our prosperity.

The Carney risk premium is not yet being demanded by the UK's creditors yet. But his girlfriends in the markets seem to be increasingly losing patience with him.