Is streaming technology saving the music industry?

- Published

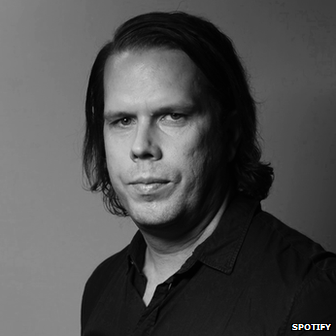

Founders Daniel Ek (left) and Martin Lorentzon launched the music streaming service in 2008

Digital technology, once accused of nearly destroying the music industry, is now being hailed as its saviour.

Online streaming services, from the likes of Spotify, Deezer and MixRadio, have flourished along with the rise of the connected smartphone and tablet computers.

In the UK, about 7.4 billion tracks were streamed on audio services in 2013, twice the total recorded in 2012, says BPI, the music industry trade body.

While digital accounted for 50% of UK record industry trade revenues last year, streaming brought in 10%, and this figure is rising fast.

As a sign of streaming's maturity, listening data will now be incorporated in the UK's official singles charts for the first time from July, the Official Charts Company announced this week.

"Last year we saw some growth in music industry revenues - the first time in ages," says Gennaro Castaldo, spokesman for the BPI. "We're pointing forward again and streaming is helping with that recovery."

Royalties row

Paul Pacifico says the Featured Artists Coalition is broadly supportive of music streaming

Streaming has its critics, not least those artists and labels who believe the service providers do not pay enough in royalties. Despite this, support is growing from within the industry.

"There are still a lot of things that need to be worked out around revenue sharing," says Jon Webster, chief executive of Music Managers Forum (MMF), which has about 400 members in the UK representing more than 1,000 artists worldwide.

"But any artist has to be on a streaming service now - it's what consumers want," he says. "It's part of the future. And if you're successful, you can still make a considerable amount of money from it."

The Featured Artists Coalition (FAC) is an organisation campaigning for fairness and equality for artists in the music industry.

It includes well-known figures on its board such as Billy Bragg, Dave Rowntree from Blur, Nick Mason from Pink Floyd, and Annie Lennox.

It is also broadly supportive.

"Technology has had a disruptive effect on the music industry without doubt, but artists can now have a dialogue with fans that they never had before," says FAC board member Paul Pacifico.

"Streaming is a model that promotes the discovery of new music. Just how the money is divided is still up for further discussion."

One of the largest streaming services, Swedish company Spotify, says about 70% of its revenues from advertising and subscriptions goes back to rights holders - the record labels, collecting societies and publishing companies.

It says it has paid out more than $1bn (£587m; 735m euros) in royalties since its launch in 2008 to the end of 2013.

Music on demand

Spotify's launch came not long after Apple unleashed its first smartphone on the world. The two technologies have gone hand in hand ever since.

Spotify's Fredric Vinna says streaming is all about connecting fans with artists

Spotify now has 40 million active users worldwide, 10 million of which pay about £9.99 a month for ad-free premium content and services.

"Streaming is about access versus ownership," says Fredric Vinna, Spotify's vice-president of product. "Now you can have up to 30 million songs in your pocket."

"We want to connect fans and artists, fans and brands, fans with fellow fans," he says.

Complex machine learning algorithms and big data analytics can guess and learn users' musical tastes - based on their previous listening preferences; age, gender and location; the playlists they create; even what time of day it is.

This kind of personalisation is key to streaming services, argues Andy Gaitskell-Kendrick, head of global product marketing for entertainment at Microsoft, which owns streaming service Nokia Mix Radio.

"Every time you log in we understand a little bit more about your tastes and how they change throughout the week," he says.

"We will even have movement sensors in Windows phones that will help us match a song list to the cadence of your exercise routine."

But Mr Vinna is also keen to stress the human element of Spotify's service.

"It's not all about algorithms," he says. "We have a big staff of music experts creating hand-picked playlists and making sure all the data behind the recommendations is correct - a lot of the work is manual and human.

"We don't want every aspect of the app to be personalised - we want users to step out of the bubble sometimes."

Microsoft's Andy Gaitskell-Kendrick thinks personalisation is key to streaming's success

Mr Gaitskell-Kendrick agrees, saying: "We think of people as listeners - we want to help them find stuff they've not heard before."

Musical disruption

When digital downloads took off in the late Nineties, file-sharing services like Napster blossomed, too.

The industry went into a tailspin as music sales virtually halved over the next decade.

"In 1999 it looked like the Napsters of this world and pirate networks were in the process of dismantling the industry," says Mr Gaitskell-Kendrick. "Consumers were ahead of the game."

One 2007 study by the Institute for Policy Innovation, external estimated that illegal downloading was costing the US economy $12.5bn (£7.3bn; 9.2bn euros) a year.

"The industry didn't know how to respond to technology at the start," says MMF's Mr Webster.

"Record labels were used to being in control. But you always have to let people consume music in the way they want to consume it. Trying to control this doesn't work," he says.

Labels have had to adapt or die, he believes, especially given the rise of companies such as BMG Rights Management and Kobalt offering record label services without insisting on owning the rights to the music.

"Artists are no longer subservient to record labels - technology has been incredibly empowering for them, giving them access to new fans from Ethiopia to Brazil," he says.

Former artists are also finding they can find new audiences, argues Mr Pacifico.

"For example, technology has been a massive enabler for Maceo Parker, James Brown's band leader in the seventies," he says.

And a spokesman for global rights agency Merlin, which represents major independent record labels, says: "Streaming drives digital growth - for one-in-five Merlin members, it accounts for more than 50% of their digital income."

Indies rising

Streaming is also playing an increasingly important part in the business of Big Scary Monsters, a small Oxford-based independent record label run by 30-year-old Kevin Douch.

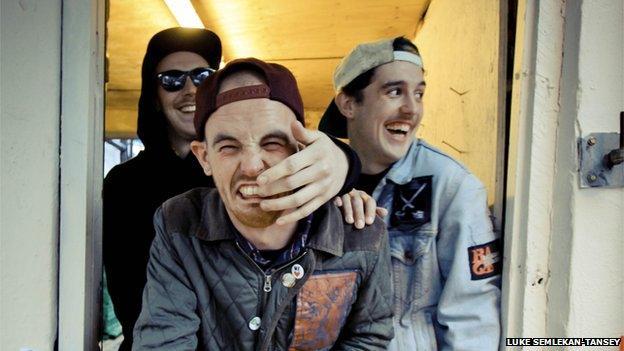

His label represents about 10-to-15 bands at any one time, including the up-and-coming punk band Gnarwolves.

"Although the internet has always been massively important for my business, allowing me to sell direct to fans, I've always viewed streaming as a promotional tool rather than a revenue generator," he says.

Streaming is helping punk band Gnarwolves gain new fans, says Kevin Douch of label Big Scary Monsters

"But next year Spotify will probably be responsible for the biggest slice of our digital sales as fans switch from iTunes downloads.

Some of his artists are "getting hundreds of thousands of streams through Spotify", he says, with the added bonus that they can link to merchandising on their own websites without Spotify wanting a cut of the revenue.

"Spotify could soon be that one page we point fans towards to get all the information they need about their favourite bands," he concludes.

But in Mr Douch's view, there's still nothing better than an old-fashioned vinyl record collection you can show off to your friends.