Can drones help tackle Africa's wildlife poaching crisis?

- Published

Drones could play a significant role in anti-poaching and wildlife conservation

An eye in the sky that can help catch wildlife poachers is the dream of many conservationists in Africa.

That dream is closer to becoming a reality thanks to rapid advances in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), or drone, technology.

Ol Pejeta Conservancy, a Kenyan 90,000-acre reserve specialising in protecting white and black rhinos, has teamed up with San Francisco-based tech company Airware, which develops drone autopilot systems.

"With the blessing of the Kenya Wildlife Service we did 10 days of testing," Robert Breare, Ol Pejeta's chief commercial officer, told the BBC.

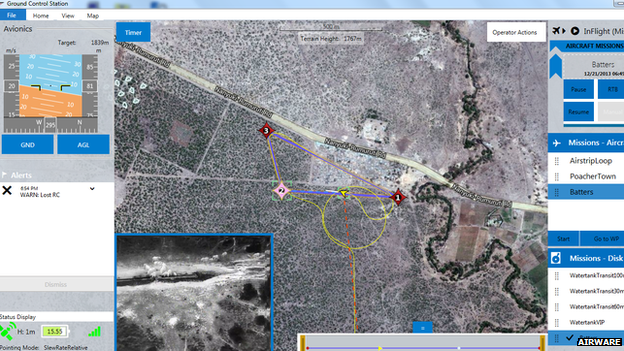

Rangers at the base could operate the drone via two laptops, one showing a map tracking the flight path, the other showing the UAV's point of view through a high-definition camera.

Rangers at base can view the drone's flight path on a map and see what it is looking at simultaneously

The drone can fly a pre-programmed route or be controlled manually

Thermal imaging cameras meant the drone could also fly at night, with the operators clearly differentiating the shapes of animals.

They could even see how the elephants' trunks changed temperature as they sucked up water from a trough.

With a wingspan of less than a metre, the catapult-launched drone flew at an altitude of about 500 feet.

"You hardly see or notice it," he says. "We don't want to startle the wildlife... or the tourists."

Jonathan Downey, Airware's chief executive, says: "At one point during testing a tractor severed the ethernet cable so we lost all communications with the aircraft.

"It was able to work this out then fly back to base. When it didn't receive any further instructions it landed by itself."

A large rhino horn can fetch as much as $250,000 in underground markets

Mr Breare envisages drones complementing, rather than replacing, the sniffer dogs and teams of armed, GPS-tagged rangers connected by a digital radio system.

But while this trial was deemed a success, both parties acknowledge that much more work needs to be done.

"The operating and autopilot systems worked flawlessly and were easy to operate," says Mr Breare, "but finding an airframe that was robust enough for the environment proved difficult."

Lucrative business

Rangers need all the help they can get in the fight against poachers.

Killing elephants for their tusks and rhinos for their horns has become an illicit multi-million dollar business, with demand particularly high in Asia.

And the trade is threatening Africa's lucrative wildlife tourism industry.

"South Africa's Kruger National Park is ground zero for poachers," says Crawford Allan, spokesman for the World Wildlife Fund's (WWF) crime technology project. "There are 12 gangs in there at any time. It's almost like a war zone."

Crawford Allan of the World Wildlife Fund's crime technology project believes drones are only part of the solution

"With a kilo of rhino horn selling for around $60,000 (£35,000), a big specimen can fetch $250,000," says Mr Breare.

"Security is a very significant part of our operating budget and this has escalated over the last two years because of increases in the price of ivory and rhino horn.

"We estimate we've had to spend an additional $2m to protect the rhino that we have," he told the BBC.

'No silver bullet'

But drones are not the whole answer, most experts agree.

"They're not a silver bullet," says Mr Breare. "Trying to find the small shape of a poacher in a 90,000-acre park is still difficult, even with high-spec night time and thermal imaging."

Mr Downey also admits that developing an airframe that is both light and strong enough to withstand Africa's rugged landscapes is still a challenge, especially when cost will be an issue for many game reserves.

While the "brains" of the drone weigh just 100g, the batteries required to power it for long-duration surveillance missions are heavy, meaning the airframe has to be bigger, and therefore more costly.

Smaller, cheaper drones come with a typical battery life of 30-90 minutes, but large game reserves "really need drones that can fly for six to eight hours," says Mr Breare.

Airware's Mr Downey estimates that drones for anti-poaching will ultimately cost $50,000-$70,000.

Higher-specification long-range drones can cost upwards of $250,000.

Larger surveillance drones with longer ranges are far too expensive for most game reserves

There is also further development needed around software that can automatically detect different animal species and count them, Mr Downey says.

'Cyber canopy'

On an African plain in the dead of night, poachers can remain invisible to rangers just 100m away.

So hand-launched drones with night vision can provide a very useful extra pair of eyes, says Scott "LB" Williams, founder and director of the Reserve Protection Agency (RPA), a not-for-profit technology consultancy.

But even when the poachers have been located, GPS-tracked rangers still have the dangerous task of arresting or seeing off the gangs who are often heavily armed and funded by organised crime syndicates.

About 1,000 rangers have been killed over the last 10 years trying to protect wildlife, the Game Rangers Association of Africa estimates.

So the RPA has been experimenting with integrating a range of technologies on the Amakhala game reserve in South Africa's Eastern Cape.

The Reserve Protection Agency's Scott "LB" Williams believes UAVs are only "one layer of the onion"

"We've designed our own tracking tag incorporating RFID [radio-frequency identification] technology and attached it to animals, rangers, vehicles, weapons and trees," says Mr Williams.

"We're putting up three large towers to pick up the tag signals and creating a kind of cyber canopy. The UAV is just one layer of the onion, not the whole solution."

The WWF's crime technology project has also been trying out this approach after receiving $5m (£3m) of funding from technology giant Google.

"Our ultimate finding was that UAVs by themselves were pointless," says WWF's Crawford Allan.

"The first thing you do need on the ground is well-equipped, well-trained rangers to react to the data coming in. Other systems - such as tagging and tracking of animals - used in combination with UAV tech makes much more sense."

The WWF, like the RPA, believes that linking all these ground and air sensors and cameras over a secure radio network is crucial in the fight against poaching.

Rangers in Kruger National Park were given a demonstration of the Skate UAV in November as a way to protect rhinos from poachers

Census taking

As well as spotting, tracking and deterring poachers, drones could also play a wider conservation role.

Mr Williams believes that longer-range drones equipped with multiple sensors and cameras will be used strategically for surveillance, data collection, and flora and fauna censuses.

Ol Pejeta's Robert Breare agrees, saying: "Currently counting animals has to be done manually from the air, which is expensive and not terribly accurate. If this could be done automatically using drones it would save us a lot of time and money."

While image recognition software that can differentiate between species at night is being developed, "we're not there yet," says Airware's Mr Downey.

But the pace of development is rapid and interest in anti-poacher drones is global.

For example, the Wildlife Conservation UAV Challenge, founded by Princess Aliyah Pandolfi of Kashmir-Robotics and supported by the RPA, has received nearly 140 entries for its low-cost drone competition.

The winners, to be announced in November, will see their designs tested in South Africa's Kruger National Park.

So drone technology is likely to play a significant part in the fight against poaching, but only as part of an integrated, ground-to-air tracking and surveillance system.

Until then, as Crawford Allan says: "Nothing beats a real dog."