Pharmaceutical industry gets high on fat profits

- Published

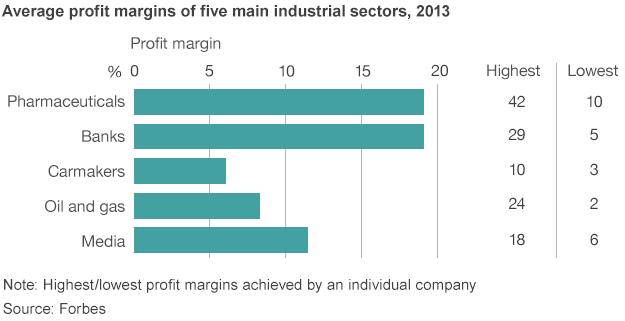

Imagine an industry that generates higher profit margins than any other and is no stranger to multi-billion dollar fines for malpractice.

Throw in widespread accusations of collusion and over-charging, and banking no doubt springs to mind.

In fact, the industry described above is responsible for the development of medicines to save lives and alleviate suffering, not the generation of profit for its own sake.

Pharmaceutical companies have developed the vast majority of medicines known to humankind, but they have profited handsomely from doing so, and not always by legitimate means.

Last year, US giant Pfizer, the world's largest drug company by pharmaceutical revenue, made an eye-watering 42% profit margin. As one industry veteran understandably says: "I wouldn't be able to justify [those kinds of margins]."

Stripping out the one-off $10bn (£6.2bn) the company made from spinning off its animal health business leaves a margin of 24%, still pretty spectacular by any standard.

In the UK, for example, there was widespread anger when the industry regulator predicted energy companies' profit margins would grow from 4% to 8% this year.

Last year, five pharmaceutical companies made a profit margin of 20% or more - Pfizer, Hoffmann-La Roche, AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Eli Lilly.

'Profiteering'

With some drugs costing upwards of $100,000 for a full course, and with the cost of manufacturing just a tiny fraction of this, it's not hard to see why.

Last year, 100 leading oncologists from around the world wrote an open letter in the journal Blood calling for a reduction in the price of cancer drugs, external.

Dr Brian Druker, director of the Knight Cancer Institute and one of the signatories, has asked: "If you are making $3bn a year on [cancer drug] Gleevec, could you get by with $2bn? When do you cross the line from essential profits to profiteering?"

And it's not just cancer drugs - between April and June this year, drug company Gilead clocked sales of $3.5bn for its latest blockbuster hepatitis C drug Sovaldi.

Drug companies justify the high prices they charge by arguing that their research and development (R&D) costs are huge. On average, only three in 10 drugs launched are profitable, with one of those going on to be a blockbuster with $1bn-plus revenues a year. Many more do not even make it to market.

But as the table below shows, drug companies spend far more on marketing drugs - in some cases twice as much - than on developing them. And besides, profit margins take into account R&D costs.

The industry also argues that the wider value of the drug needs to be considered.

"Drugs do save money over the longer term," says Stephen Whitehead, chief executive of the Association of the British Pharmaceuticals Industry (ABPI).

"Take hepatitis C, a shocking virus that kills people and used to require a liver transplant. At £35,000 [to £70,000] for a 12-week course, 90% of people are now cured, will never need surgery or looking after, and can continue to support their families.

"The amount of money saved is huge."

True, but just because you can charge a high price for something does not necessarily mean you should, especially when it comes to health, critics such as Dr Druker might say. Shareholders, who big pharma companies ultimately have to answer to, would have little time for such an argument.

No loyalty

Big pharma companies also say they only have a limited time in which to make profits. Patents are generally awarded for 20 years, but 10-12 of those are typically spent developing the drug at a cost of about $1.5bn-$2.5bn.

This leaves eight to 10 years to make money before the formula can be taken up by generic drug companies, which sell the medicines for a fraction of the price.

Once this happens, sales fall by 90%-plus. As Joshua Owide, director of healthcare industry dynamics at research company GlobalData, explains, "Unlike other sectors, brand loyalty goes out the window when patents expire."

This is why pharma companies go to such extraordinary lengths to extend their patents - a process known as evergreening - employing "floors full of lawyers" for this express purpose, one industry insider says.

For a drug raking in $3bn a quarter, even a one-month extension can be worth huge sums of money.

New formulations, combining two existing drugs to give a wider use, and enantiomers - a mirror image of the same compound - are some of the legal ways to eke out patents. But some drug companies, including the UK's GSK, have been accused of more underhand tactics, such as paying generics to delay the release of their cheaper alternatives.

As the loss of sales at the big pharma companies far outweighs the revenue made by the generics, this can be an attractive arrangement for both parties.

Courting doctors

But drug companies have been accused of, and admitted to, far worse.

Until recently, paying bribes to doctors to prescribe their drugs was commonplace at big pharmas, although the practice is now generally frowned upon and illegal in many places. GSK was fined $490m in China in September for bribery and has been accused of similar practices in Poland and the Middle East.

The rules on gifts, educational grants and sponsoring lectures, for example, are less clear cut, and these practices remain commonplace in the US.

Indeed a recent study, external found that doctors in the US receiving payments from pharma companies were twice as likely to prescribe their drugs.

This may well exacerbate the problem of overspending on drugs by governments. A recent study by Prescribing Analytics suggested that the UK's National Health Service could save up to £1bn a year by doctors switching from branded to equally effective generic versions of the drugs.

Big pharmaceutical fines

$3bn

Glaxo SmithKline, 2012, over promoting Paxil for depression to under-18s

$2.3bn

Pfizer, 2009, over misbranding painkiller Bextra

-

$2.2bn Johnson & Johnson, 2013, for promoting drugs not approved as safe

-

$1.5bn Abbott, 2012, over illegal promotion of antipsychotic drug Depakote

-

$1.42bn Eli Lilley, 2009, for wrongly promoting antipsychotic drug Zyprexa

-

$950m Merck, 2011, for illegally promoting painkiller Vioxx

This all may change when new rules in the US and UK will force doctors to disclose all gifts and payments made by the industry.

Drug companies have also been accused of colluding with chemists, external to overcharge for their medicines and of publishing trial data that highlight the positive at the expense of the negative.

They have also been found guilty of mis-branding and wrongly promoting various drugs, and have been fined billions as a result.

The rewards are so great, it would seem, that pharma companies have continually been prepared to push the boundaries of legality.

'Undue influence'

No wonder, then, that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has talked of the "inherent conflict" between the legitimate business goals of the drug companies and the medical and social needs of the wider public.

Indeed the Council of Europe is launching an investigation into "protecting patients and public health against the undue influence of the pharmaceutical industry".

It will look at "particular practices such as sponsoring health professionals by the industry... or recourse by public health institutions to the knowledge of highly specialised researchers on the pay-rolls of industry".

No matter what the outcome of such investigations, however, the pharmaceutical industry is facing fundamental change, as the traditional model of developing drugs breaks down due to rising costs and scientific advances.

The cosy world of big pharmaceuticals is under threat like never before.

This is the first in a two-part series on pharmaceutical companies. The second looks at how and why fundamental change will take place in the industry.

- Published2 July 2014

- Published4 June 2014

- Published27 May 2014

- Published14 May 2014

- Published14 May 2014

- Published4 November 2013