Pharmaceuticals industry facing fundamental change

- Published

Pharmaceuticals is an extraordinarily profitable business.

The most profitable, in fact, looking at figures for last year.

But for how much longer is the question occupying the minds not just of big pharma executives, but of health professionals and governments the world over.

There are already signs of trouble ahead - thousands of job losses and widespread consolidation are hardly characteristics of an industry in rude health.

But this is just the beginning of a process that could fundamentally change the pharmaceutical sector forever.

'Little breakthrough'

For a start, big pharmaceutical companies are no longer providing the service they once did.

"The system has served us well in terms of developing good new medicines, but in the past 10-20 years there has been very little breakthrough in innovation," says Dr Kees de Joncheere at the World Health Organisation.

Of the 20 or 30 new drugs brought to the market each year, "many scientists say typically three are genuinely new, with the rest offering only marginal benefits," he says.

This dearth of genuinely new potential blockbuster drugs is a grave problem for big pharmas, and of course society at large, particularly given the industry is falling off a patent cliff the like of which it has never seen.

"Over the past three or four years, we have seen the biggest collection of patent expiries in history," says Stephen Whitehead, chief executive of the Association of the British Pharmaceuticals Industry (ABPI).

"This has cost the industry some £150bn ($240bn)."

Also weighing heavily on pharma companies is the process known as stratification. Scientific advances have led to a far better understanding of both genetics and disease, which means individual drugs can now be targeted far more directly at a much smaller number of patients.

Whereas previously one drug would be used to treat different types of cancer, for example, now different strains can be treated with a specific medicine.

The cost of developing these drugs remains high, typically $1.5bn-$2.5bn (£900m-£1.5bn), but the market for them is tiny - in some cases only 100-150 patients.

Fair price?

This all means drugs are becoming increasingly expensive, and prohibitively so in some cases.

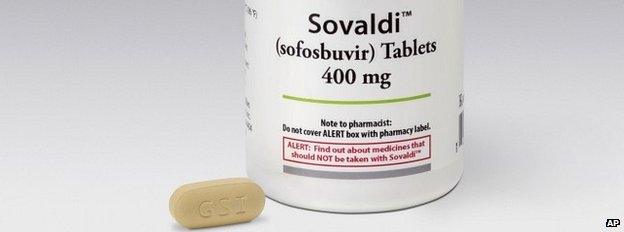

Gilead's new hepatitis C drug Sovaldi - costing upwards of $100,000 for a full course - has caused quite a stir.

"Increasingly questions are being asked," says Dr de Joncheere. "Are we getting a fair price? Are we getting enough transparency in research and development?

"If France were to treat all its hepatitis C patients with Sovaldi, it would add €1.5bn ($1.9bn; £1.2bn) to the country's drugs bill.

"[These kinds of drugs] are just not affordable any more."

And particularly so when fragile economic growth and high debt levels are squeezing government budgets across the world.

Even in the US, where free market pricing rules absolutely, Congress is becoming increasingly concerned about the price of some drugs.

Neglected drugs

And it's not just the cost of the drugs that are being developed that is a big problem, but those that aren't.

Big pharma companies are in the business to make money, so will generally develop those drugs that offer the greatest potential for profit.

This means a number of important drugs are neglected - the current Ebola crisis being a case in point.

Previous outbreaks over the past 30-40 years have been nothing like as serious as that which has claimed thousands of lives in West Africa and threatens to spread to the more developed world.

But the reason why there are so few drugs in the pipeline has more to do with affordability - developing economies do not have the kind of money needed to pay for what would be an expensive vaccine, and no amount of public pressure will override the profit-making incentive of the big pharma companies.

The pharmaceutical industry had been slow to develop an Ebola vaccine before the recent outbreak

Antibiotics is another example. These vital anti-bacterial drugs have been virtually ruined by trigger-happy GPs and patients who don't stay the full course. Resistance has built up to such a degree that, soon enough, these drugs will no longer be fit for purpose.

But new antibiotics would need to be affordable, or restricted to those that truly need them. Either way, there is little incentive for private companies to enter the market.

As Dr Stephen Godwin, senior research director at the Planning Shop International, says, "If you're only using it for seven to 10 days, it's a whole lot more difficult to make a profit than on a medicine people have to take every day."

Radical change

No wonder, then, that "the [current] model has run out of steam" as Dr de Joncheere puts it.

Big pharma companies are facing a huge drop in revenue from blockbuster drugs coming off patent, while those increasingly difficult-to-find replacements are simply becoming too expensive.

And without generating revenues through sales, these companies will struggle to fund the development of new life-saving drugs.

Big pharma facts

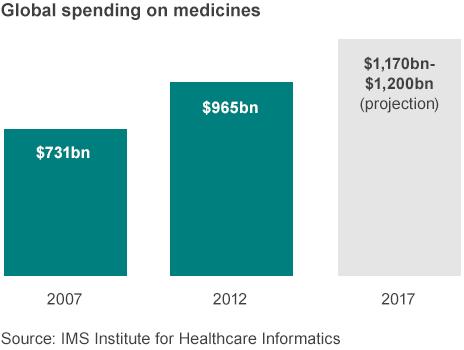

Total global spending on medicines will exceed $1 trillion for the first time in 2014

Global spending on prescription medicines is expected to increase by $205bn-$235bn in the five years to 2017

The US, EU5 (Germany, France, Italy, UK and Spain), Japan and China account for just under 70% of total global medicine spending

In 2012 in developed economies, 72% of all spending was on branded drugs, with 16% on generics

Spending on traditional pharmaceuticals in emerging markets is expected to rise by 69% over the next five years

Source: IMS Health

In the UK, the ABPI negotiates with the government to agree a cap on the National Health Service drugs bill - this year and next there will be no rise.

But longer term, more radical approaches will be needed. One obvious solution, which is already taking hold, is pharma companies working in partnership with government - a great deal of work has already been done to help in the fight against Aids, malaria, meningitis and tuberculosis, for example, while work on developing new antibiotics is under way.

They will also have to work more closely with each other, a process that has begun already with the multi-billion-dollar deal struck earlier this year between Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline.

Raising money on financial markets, for example through long-term bonds, will also be needed to plug funding gaps.

Both national governments and multi-national bodies such as the European Commission will have to devote more resources to fund research and development, rather than relying on the private sector, while third parties such as the Bill Gates Foundation will have a bigger role to play alongside the charitable sector.

Collaboration and partnership, then, may have to take the place of profit and competition as the key words in the development of the medicines of the future.

And that may be no bad thing for all of us.

This is the second in a two-part series on pharmaceutical companies. The first looked at the extraordinary profits made by drug companies.

- Published6 November 2014

- Published29 October 2014

- Published23 October 2014

- Published22 October 2014

- Published2 July 2014