Joining up Ghana's healthcare to save lives

- Published

The Motech platform follows mother and baby from conception through the early years

Giving birth in Sub-Saharan Africa is a risky business.

It kills more mothers and babies than anywhere else in the world, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), external.

Some progress is being made. In Ghana, for example, the Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) declined by 49% between 1990 and 2013 to 380 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2013 - but this still leaves some way to go to reach the United Nations Millennium Development Goal, external of 185.

Call me

On the veranda of the small, squat bungalow that is the Ahentia Community Based Planning and Service (CHPs) clinic sits a group of women. Some are pregnant, some nursing babies, they are waiting patiently to see the community health officer.

The Ahentia Community Based Planning and Service (CHPs) clinic lies at the end of a dusty road on the edge of a small village

Waiting for their appointments, Alice Hanson (left), Sophia Pabie, Joycelyn Yawson and Cynthia Larbie catch up on the gossip

What makes this situation a little different is that each of them has been reminded about their appointment by messages sent to a mobile phone, through a system called Mobile Midwife.

They also receive regular messages with individually-tailored information on everything from eating properly to when to give up manual labour to important treatment and vaccination advice.

Cynthia Larbie is pregnant with her second child.

Alice Grant-Yamoah talks about mobile health technology in Ghana.

"When I was pregnant for the first time I would have enemas, which are supposed to be good for you and the baby. But listening to messages from Mobile Midwife, I learnt they can cause your baby to be aborted," she says.

"The reminders really help, too. Because I wasn't sure when my first baby would arrive, I gave birth at home, but this time being told that I'm close to delivery means that I'm prepared and ready to give birth at the clinic."

Getting women in rural areas to attend antenatal appointments regularly isn't easy, says community health officer Alice Grant-Yamoah.

Convincing women to come for regular antenatal appointments has been difficult

"Most of the mothers are illiterate, so when we wrote the date [down], they forgot about it," she says.

"[Mobile midwife] saves mothers' lives. Because in this community we believe … superstitions. For example you go and meet a mother at home, telling [her] to come for antenatal care.

"[They say] If I come the evil eye will look at me and I will lose my baby. That's what I did with my previous babies and I lost the babies."

Mobile midwife is part of the Ghana mobile technology for community health (Motech Ghana) initiative - a collaboration between the non-profit organisation Grameen Foundation and the Ghana Health Service.

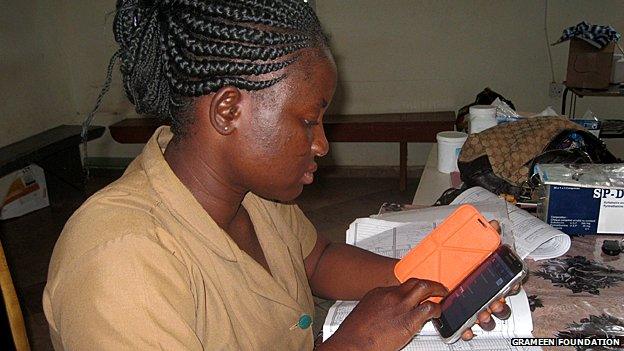

A community health worker uses the new Android-based MOTECH app

In a country where there are more active mobile phone lines than people (although using several Sim cards is common, so this doesn't mean that everyone has a mobile phone), using the technology to reach women and connect healthcare facilities makes sense.

When a woman signs up for the service, she is assigned a unique number.

After each appointment, the nurse updates her medical records electronically using a mobile phone. By reviewing a digitally-generated monthly report, she can see who has had the correct vaccinations, for example. It also means that the health service can gather centralised data on maternal health in the region.

The platform is now used in seven districts across Ghana. A desk-top nurse application has been developed to make it easier to enter large amounts of data, as well as an app for android smartphones.

Patricia Antwi: "We've seen an increase in antenatal care coverage as compared to the years when we didn't have the Mobile Midwife service"

"We've also seen an increase in immunisation coverage, because the messages are around from pregnancy to the start of life. We've seen an increase in the number of mothers coming to the facility to deliver. And also we've seen that many more of the mothers are very knowledgeable about health issues," says Patricia Antwi, district director of health services for Awutu-Senya district.

Challenges remain, however - in rural areas network coverage can be patchy, and communities are often off the national grid, with no way to charge a mobile. And mobile phone ownership is lowest amongst poor, rural women, according to Eddie Ademozoya, Grameen's head of implementation for the Motech Platform.

"Mobile literacy has [also] been an issue in a developing country like this," he says.

"We have piloted a system of equipping Mobile Midwife agents with a solar charging device so that they can charge the mobile phones of women in the communities for a fee. It's designed in the form of a business-in-a-box."

Grameen Foundation's Eddie Ademozoya

For the Grameen Foundation, the time has come to hand over the running of the platform in Ghana to the Ghana Health Service. But that doesn't mean that their involvement is over.

"We've re-engineered [the Motech platform] to make it more robust, to make it scale, so it can serve the whole nation instead of just districts," says Grameen's director of technology innovation David Hutchful.

The suite is now being offered as an open source download, external, and is being used elsewhere in Africa, Asia and South America not only for maternal health but as an HIV medication reminder service and for general health management among other things.

Make a claim

Several worlds away from rural Ghana lies the capital, Accra. It's a bustling, booming, often gridlocked city with budding aspirations to rival Africa's technology hubs Nairobi and neighbouring Lagos.

Like much of west Africa, many of the clinics and other healthcare facilities servicing the city still rely on time-consuming paper and print to coordinate operations - meaning there's often (if not usually) a large backlog of paperwork and insurance documents waiting to be dealt with.

"A few months ago, I walked into a hospital that we are engaging and I found a notice that says, if you are from a particular insurance company, services have been suspended," says Seth Akumani, chief executive and co-founder of start-up ClaimSync.

"So, if you are, for instance, a patient who is returning for a follow-up visit you basically have to pay cash or you will be turned away."

ClaimSync started life at the Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology (MEST) in Accra.

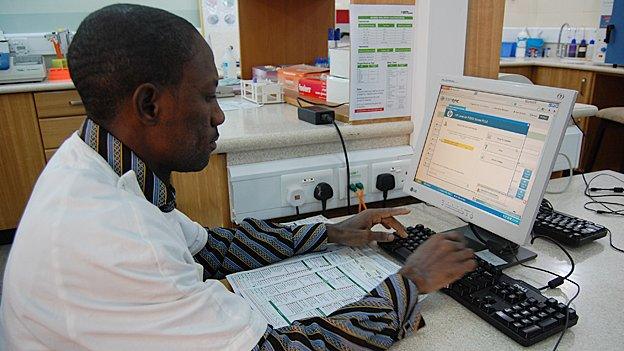

Some clinics in Ghana are moving to digital health records to improve efficiency.

"Our initial idea was to build a platform to make it easy for patients to access their records," says Mr Akumani. "We went out and talked to a lot of hospitals, the insurance companies, to try and understand the main points. Then we found out there is actually a gap between the hospitals and insurance companies."

The software creates an integrated electronic medical records system that aims to link every department in a healthcare facility to a central database, integrating the process so that everyone from the receptionist to the doctor to the lab to the pharmacy can track a patient's progress.

This means that not only should there be no chance of mistakes being made because different departments don't speak to each other, but the paperless system should save time and increase efficiency.

ClaimSync's Seth Akumani

Insurance claim documents can be generated automatically and sent off. And if the insurer is also using ClaimSync software it can be received almost immediately.

"Insurance companies can log on to our online platform and receive the claims in batches," says Mr Akumani. "They can drill down and see the details of a single paper claim. They can accept or reject items on these claims and import them into the internal system for further processing."

The platform is currently being used at the Danpong Clinic in Accra.

Osei Antobre is the Medical Services Manager at the facility, and says that the software has improved confidentiality and increased efficiency.

Now clients give permissions and personal details once only, rather every time they visit.

"Since the introduction of the software....we just visit the database that we have there, their information, and then we process them right from there. The speed of the process is top for us."

The ClaimSync platform aims to be almost completely paperless

Laboratory tests can be tracked through the software, and billed for

ClaimSync's integrated approach has won fans - the startup has been snapped up by Dutch biometric identity management company GenKey.

According to Mr Akumani this means that they will be able to add GenKey's technology to the platform, which uses fingerprints and other biometric data to identify claimants accurately. This should help weed out fraudulent insurance claims and open up an international market, he believes.

Healthcare facilities where paperwork gets in the way of patient care, and where a lack of properly integrated technology means mistakes are more likely to happen, are not unique to Ghana.

They're not even unique to the developing world. And the appetite for technology to plug these gaps is massive.

But having answers to these problems provided by Ghanaians for Ghanaians is important, according to Grameen's David Hutchful.

"It's important that a platform like Motech was first sort of thought of in Ghana, because there are a lot of unique problems and issues that affect Ghana and other developing countries.

"Motech initially was developed with Kenyan developers and then it was opened up to the rest of the world. We have Indians working on it, we have people in Poland working on it, people in the US working on it.

"But having it start from here was very important - to have that sort of local understanding of the problem feed into the actual code that ends up this being this whole platform."