Wine fraud: How easy is it to fake a 50-year-old bottle?

- Published

With vintage wines fetching prices in excess of $200,000, wine fraud has become a lucrative business

Rudy Kurniawan was sentenced to 10 years in jail for committing wine fraud. But just how easy is it to fake a fancy bottle of Burgundy?

Wine fraud was a problem in classical Rome and it continues to be one now. Some estimate that over 5% of wine consigned and sold at auction is fake.

But even though it is a very big problem, it is a very difficult thing to do.

"There is a distinctive taste in aged wine," says wine chemist Andrew Waterhouse, of the University of California, Davis.

That taste?

"Canned asparagus," he says.

Old wines - mostly those from the Burgundy and Bordeaux regions of France - have lost the majority of their tannins, giving them a softer taste reminiscent of the spring vegetable.

But taste is only one part of the equation. "It is the experience of drinking something that's quite rare that's appealing," explains Prof Waterhouse.

Counterfeit kitchen

So how to do it? Mr Kurniawan's case provides a good road map.

Mr Kurniawan managed to sell over $20m (£11.9m) worth of fake wine for more than a decade before he was caught.

A courtroom sketch of Mr Kurniawan, who was sentenced to 10 years in jail and ordered to pay $23.8m

Geoffrey Troy is a wine merchant in New York who became suspicious when Mr Kurniawan bought bottles of 1974 Domaine de la Romanee-Conti. It was a good, but not great, vintage of French Burgundy.

"A serious collector wouldn't be buying off-vintages," says Mr Troy.

"He was so eager to buy these bottles that I suspected that he could possibly be using them to change the vintage at some point and sell them for a lot more money."

Five ways to spot a fake vintage wine

Label - Labels that are not on proper paper stock from the period, or do not have the proper font, are a giveaway

Capsule - Some fakes swap wax for foil at the top of the bottle, or use the wrong colour wax

Cork - Often branded with the name of the winery and the vintage, the font and shading can be clues

Wine colour - Old wine has its own colour, some fakes don't

Glass - Very old bottles have distinctive glass

Source: Allan Frischman, external, Hart Davis Hart Wine Auction house

And that's exactly what Mr Kurniawan was doing in his kitchen in Arcadia, California - essentially creating a "better" vintage by mixing old, good-but-not-great wines with some newer, vibrant pinot noirs.

Give it a shake, put it in an old bottle, smack on a vintage label - say, one from 1985 instead of 1982 - and voila.

"He could take a $200 bottle and turn it into over a $1,000 bottle," says Mr Troy.

Mr Troy sold several bottles of wine to Mr Kurniawan, but came to suspect him

Unless you are used to drinking fine vintages regularly - which not that many people are, given that they can cost thousands of dollars - the taste would not necessarily ring any alarm bells.

"By blending the fruitiness of a new wine with the aged character of the old wine he would approximate in some manner a very, very good aged Burgundy," explains Prof Waterhouse.

Label lies

Furthermore, in choosing extremely old vintages to consign to auctions, Mr Kurniawan made a savvy choice.

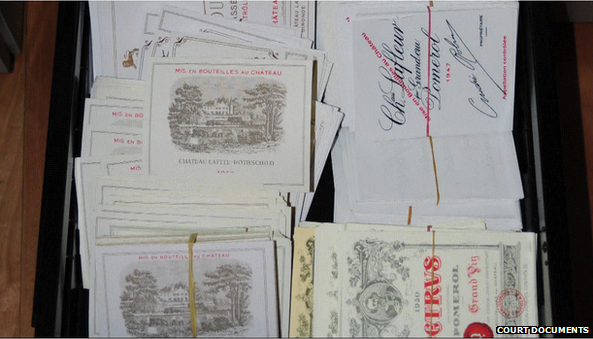

When police raided Mr Kurniawan's house, they found his kitchen filled with wine fraud supplies

"Back in the 1920s and 30s, many of the producers never branded their corks, or used capsules (the foil or wax at the top of a bottle) that were plain," explains Mr Troy.

Those plain markers were easy to forge. What tripped up Mr Kurniawan was the label.

In June 2008, Mr Kurniawan attempted to consign some $2,613,860 of wine to auction house Hart Davis Hart.

Allan Frischman, a vice-president and wine inspector with Hart Davis Hart, rejected the lot.

"It didn't really require a lot of study - most of the wines we were able to tell pretty easily from photographs of the labels that they were not authentic," he says.

Mr Frischman says that less than 2% of the wines he has inspected at Hart Davis Hart have been forgeries, and the labels are often what tip him off to frauds.

To find a fraud

Mr Kurniawan's case has sent shockwaves through the small world of vintage wine collectors, auction houses, and vineyards. Some say it will take years to figure out just how many of his fake bottles are still in the market.

Mr Kurniawan had over 12,000 wine labels in his possession, but they didn't fool experts

That has led for calls to have auction houses examine more carefully the provenance of bottles, as well as for better fraud detection technologies.

Can tech prevent frauds?

Patrick Eischen cites his personal experience with wine fraud as the motivation behind his firm, Selinko, which uses chip technology to help prevent old bottles from being reused.

A part-owner of a vineyard in Italy, he found his wines were being widely counterfeited in China.

So Mr Eischen developed a technology that takes advantage of the same thing in many credit cards - microchips - which are then tagged using an operator's phone.

"We developed a technology which goes on the capsule of the bottles so that when you open them it deactivates the system," he says.

This way, it is not just auction houses and experts who are looking to prevent fraud, but vineyards and consumers as well.

"One big problem is most of the analyses require opening a bottle," explains Prof Waterhouse.

"Given the value of these bottles and the scarcity, most people will say 'maybe not'."

Some have pointed to isotope analysis, external that could better break down the origins of the wine, external in a bottle, and another professor at UC Davis, Matthew Augustine, external, has recently published papers, external on using magnetic resonance imaging to determine if wine has turned into vinegar.

Others have argued for chip technology to be put on all bottles, so that old bottles could not then be re-used to package fake wine.

But for now, those who have been duped can take comfort in joining an elite group that spans the centuries.

"Not even our nobility ever enjoys wines that are genuine," complained Pliny the Elder, back in First Century Rome.

- Published7 August 2014

- Published24 July 2014

- Published21 December 2013