The Spanish miners’ fight for survival

- Published

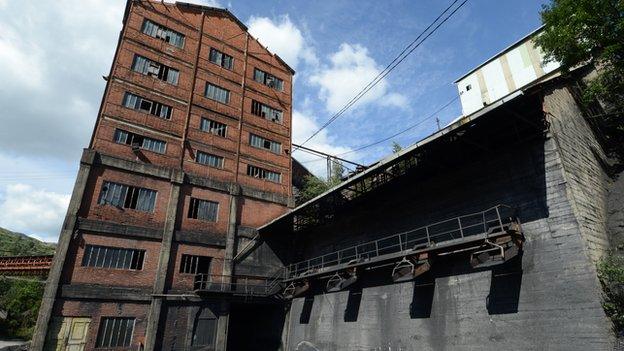

The landscape of northern Spain's Turon Valley is littered with abandoned mines. As the industry which once sustained them dwindles, locals are concerned about what will become of their culture and way of life.

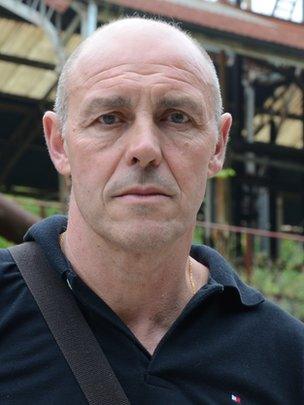

Felipe Buron cuts a lone figure as he walks the worn woodland paths that wind past the old pits.

"You need to realise that coal mining goes back many generations," the former miner says.

"The rivers were black... the sky was black with coal powder. That was life. We didn't know anything else."

Coal dust no longer blackens the Turon countryside - and what was once a way of life is now a rapidly receding memory.

Over the past 20 years, the number of miners in Spain has dropped from 45,000 to just over 3,000 - and it is set to fall even further.

The European Union says state subsidies to mining should end by 2018.

It is estimated that for the last two decades an average of 1bn euros (£800m) a year has been given in economic aid to mining areas like Turon.

That kind of support is hard to maintain in tough economic times - and for such a small number of miners.

Felipe Buron lost his mining job 20 years ago

The government insists that it can no longer afford to subsidise such an uncompetitive industry.

In 2012 it announced plans to slash mining subsidies by 64% - from 300m euros to 110m euros.

Fighting and striking

In the 1980s the town of Mieres in Asturias saw ugly clashes as striking miners took to the streets and fought running battles with the police.

Felipe Buron says it has always been something that came with the territory.

"It was always fighting, always fighting... Striking for safety, striking for wages, for solidarity with other sectors.

"It was always like that. That was our working life."

When the mines started closing in the 1990s, Buron and many others were offered pre-pensions - a portion of their salaries, paid for by a special government budget, until they reached retirement age.

It was an offer that could not be refused.

Buron now spends his time running the Santa Barbara Association, named after the patron saint of the miners. It is dedicated to preserving their history and culture.

Singing their troubles

Another group of former miners try to keep traditions alive in El Coro Minero de Turon - the miner's choir of Turon.

The men dress as if they were still heading down into the bowels of the earth - in blue overalls, with white hard hats hanging from their belts.

But instead of their hands, they now use their voices.

The miners' choir of Turon sing the miners' anthem which is often sung during strikes and protests in Spain

The hardened men sing softly of their patron saint Santa Barbara, a song about blood, sweat, tears and a mining tragedy.

It is the anthem of all Spanish miners.

Francisco Lombardia sang it as he took part in the last big miners' strike in 2012.

"The song fills me with emotion. I have sung it with my colleagues in many marches and celebrations.

"It's our flag. It's like the magic word that brings you together - like the chants of a football team or the 'oles' of the bullfighters."

Lombardia lives in Villablino, in Leon - another area with a history of mining.

Miners fire handmade rockets at riot police in the 2012 mining strike

The Black March

When the Spanish government threatened to slash subsidies for the mining sector two years ago, Lombardia and others took to the streets and hills and clashed heavily with the police.

He says: "When they don't listen to you and bring hunger to your doorstep you have to choose: you fight or you starve."

The violence lasted for weeks and culminated in what became known as the Black March - which saw thousands of striking miners walk 300 miles to Madrid to try to confront the government face to face. After this show of force, union leaders told them to go home rather than continue protesting in the streets.

Lombardia felt this was a betrayal, and for him it was the beginning of the end.

"I came back home, I sat with my wife and my daughter and told them, 'We will not live off mining any more.'"

Local people say it is hard to accept that an agreement with the EU is forcing the closure of their pits - especially when they hear about new mines being opened in other countries like Germany.

Another miner, Carlos, fears they will not even make it to 2018 - when the EU wants Spanish mining subsidies to end.

There are only 3,000 miners left in Spain

He says: "It looks like they will fire us. They will fire us soon, because it doesn't look like anything is going to get fixed.

"Only the pensioners will remain here. The rest will have to leave."

Carlos is an independent contractor who will not get the generous pre-pension payments offered to miners who lost their jobs 20 years ago.

People have no food

His family rely solely on £500 a month in child benefit payments.

"You can be without food, but before my daughter starves I will look for money wherever I can.

"It is painful to say that five of our colleagues are eating in soup kitchens. Not even their children have food. It is terrible that we've reached this point where people have no food."

Some former miners are managing to make a living away from the pits.

Lombardia has started his own business making wood pellets to use as fuel in stoves and boilers.

It has made him more optimistic about the future, but he blames the previous generation of miners for making life harder for people like him.

"When they started to wind down the coal industry, people were bought off with the pre-pensions and everyone was happy," Lombardia says.

"But they didn't realise that they were getting good salaries for themselves but mortgaging their children's lives. That's what happened."

Back in the Turon Valley, Felipe Buron says his generation were put in an impossible position.

"We are all responsible. But one thing is clear: we didn't ask for the pre-pensions, we didn't ask for the mines to close down.

"The government came and said: 'There's this on offer.' I don't feel guilty at all. Many people point the finger, but if they were in the same position they would take the deal."

A Song For Spanish Miners is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 11:00 BST on Thursday, 4 September and will be available on BBC iPlayer.

- Published3 August 2012

- Published15 June 2012

- Published14 June 2012