3D printing: From racing cars to dresses to human tissue

- Published

Print it: About 5% of the Strakka Dome is 3D printed. Within the next five to 10 years Strakka's Dan Walmsley thinks that's likely to be closer to 70-80%.

"It's a very exciting technology, it gives us the benefit of reduced lead times, reduced costs and really increases the flexibility for our engineers to be creative.

"Concept to final product used to be a minimum of maybe four weeks, whereas now it can be the next day."

Strakka Racing's Dan Walmsley is talking about their new prototype car, the Strakka Dome S103.

It's a racer that has to be hardy; it's designed for the World Endurance championship, external, a series that includes the Le Mans 24 hour. In that one race it will travel further than a F1 vehicle does in an entire season.

"[3D printing] enables us to try things, to test things, sometimes we're right, sometimes we're wrong, but it gives us a clear direction, it enables us to extract the best performance from the car."

We're not chatting by the racetrack at Silverstone (which is where the Strakka team is based) - we're at the 3D Print show, in the heart of the City of London.

Strakka have been working with one of the major players in the industry, Stratasys, to develop components for their cars, external.

They'd previously used the technology for rapid prototyping.

The dash panel on the car is 3D printed - it's cheaper than manufacturing small runs of components

Under the bonnet lie other components - like this printed brake duct. The car has a top speed of 200mph plus, and will make its debut in Brazil in October

Strakka's Dan Walmsley says although other race teams use 3D printing for rapid prototyping, he believes the Dome is the first race car to have a substantial quantity of printed parts

"We had to go though a bit of a mindset shift, because our experience of 3D printing in the past ... was quite powdery," says Mr Walmsley.

"But as soon as we saw these components - they're strong enough, they're light enough, they really can compete against cutting edge technologies in terms of materials.

"Whilst we've probably underutilised it on this car, in the future you're going to see cars with a much higher proportion of it."

The car has 3D printed brake ducts, air intake, dive planes and dash panel, among other things.

The technology has come a long way from rough novelty plastic objects made from coloured filament (although consumer versions are likely to rely on this for some time to come).

While Gartner says mainstream consumer adoption of the technology, external is probably five to 10 years away, uptake for business and medical purposes is far faster.

Canalys meanwhile sees the market reaching US$16.2bn in 2018, external - growing at a rate of nearly 46% a year.

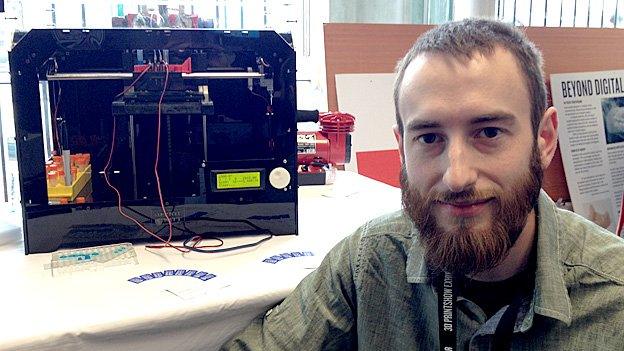

3D printing works by gradually building the object you want to print as a three dimensional matrix, layer by layer, as this Makerbot Replicator is doing

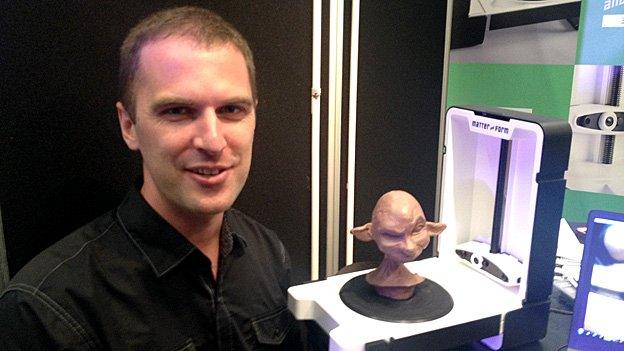

Scanning the room: How do you get your object into a CAD file? Use a scanner of course. Toronto-based Drew Cox's low-cost scanner Matter and Form started life on IndieGoGo and costs $579

My3Dtwin can take a full body scan of you and turn you into your favourite super hero - in miniature

Dress it up

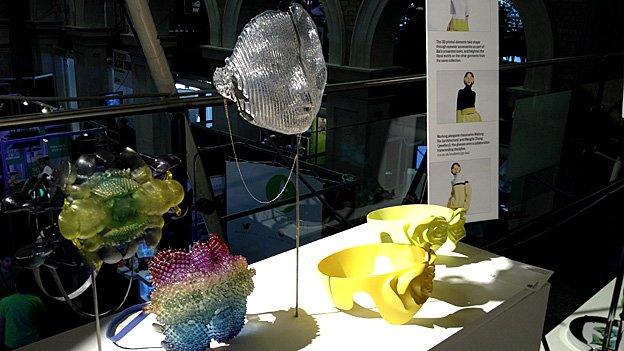

Dutch designer Iris Van Herpen, external has used 3D printing since 2010, Australian XYZ Workshop created the InBloom Dress, external in 2014, and Pringle of Scotland used it, external in their Autumn/Winter ready to wear 2014/15 collection. Fashion likes 3D printing.

Pringle of Scotland used 3D printed fabric created by material scientist Richard Beckett to create these garments

Don't lose your head: 3D printed millinery by designer Gabriela Ligenza

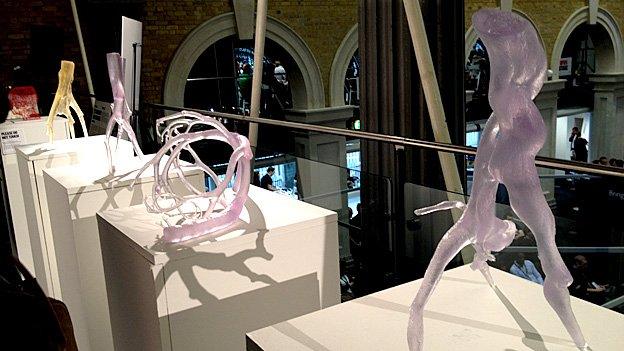

The 3D printed dress by Israeli designer Noa Raviv is part of her graduate collection

Noa Raviv is a young Israeli designer. She worked with Stratasys to develop a collection of garments featuring intricate, spidery ruffles and flounces created on a printer.

She says the technology offered exciting possibilities to create unique garments, but as yet has no plans to sell the pieces.

"I got many offers, but for the moment it would be really complicated to make more copies of this collection, as the process is at the moment quite expensive, and the other pieces are hand stitched."

But she points out that, while fabrics have yet to make it to the mainstream, 3D printed accessories are far more accessible.

Wonderluk rings 3D printed in gold - the company is also experimenting with titanium

Andre Schober (r) and Wonderluk co-founder Roberta Lucca have been trading for four months

Andre Schober is co-founder of online jewellery and accessories start-up Wonderluk.

Customers choose items and customise them. Pieces are then printed and delivered within two weeks.

"I think we exist because of 3D printing. 3D printing allows us to do what we do. But I wouldn't say that 3D printing is for us [the selling point]." he says.

"We mention that we 3D print, but our products need to stand up in their own right. The designs need to convince."

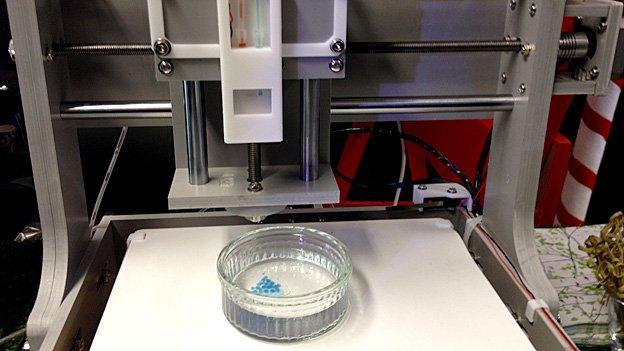

Cambridge-based design studio Dovetailed says their printer creates bespoke 'fruit' using spherification

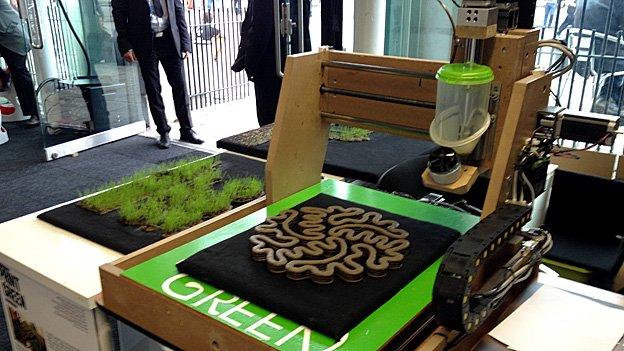

Print Green is a project that prints soil, designed at the University of Maribor, Slovenia

Lights, action

The film industry uses 3D printing in the creation of costumes and props.

"Part of what 3D printing is letting us doing is working with designers on the other side of the Atlantic," says Grant Pearmain, director of costume and props specialists FBFX.

His company has worked on an impressive list of Hollywood blockbusters, including Marvel franchise films like Captain America and Thor: Darkworld, which were filmed in the UK. The most recent was Guardians of the Galaxy.

"We've got concept designers in Los Angeles who will send us concept models in 3D, that we can then take over finish off, and.... print off what was started in America effectively."

The cast for the Star Lord helmet worn by Chris Pratt in Guardians of the Galaxy was printed. The actual prop (pictured) has 3D printed detailing

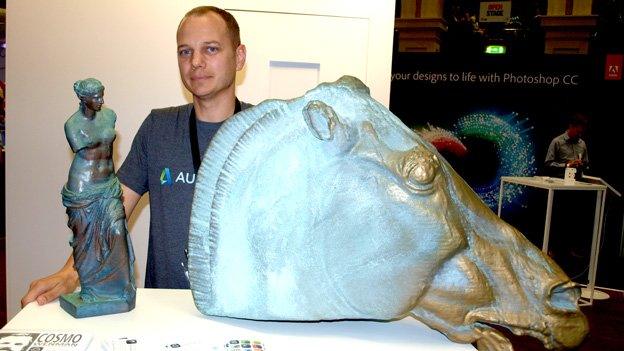

Design giant Autodesk is the company behind thousands of CAD (computer assisted design) files - which tell the printer what to print. So heavily invested are they in 3D printing the company has announced their own open source printer.

"I think verbally it's made the leap to mainstream," says the Autodesk's Jesse Harrington. "I think manufacturing wise we're really close. If you walk around here you see a lot of metals, there's a lot of ceramics, people are doing really interesting stuff with casting, carbon fibre, there's a lot of that stuff coming out."

"The consumer side - the cost is driven down for... printers, so now we have take the big next step and teach those things.

"Until we really get to that point where we can really tell people what to make, or companies like Hasbro, Disney, Marvell, start releasing some of these files so that kids can make their own toys, I think that's when you'll see the big adoption happen."

Autodesk's Jesse Harrington with 3D printed sculptures by artist Cosmo Wenman made on a Makerbot printer

Printed anatomy

Healthcare is a rapidly growing market. Dentistry has used 3D printing for some time to creature dentures, and it's now used in maxillo facial surgery to help repair parts of the jaw.

It's been used to create prosthetic devices, including ears and robotic arms.

At the (sometimes literally) bleeding edge it starts to sound more like the replicator from Star Trek, like printed blood vessels, kidneys and other organs.

Alan Faulkner-Jones is a PhD researcher at Herriot Watt University who has built his own 3D bio printer.

"Bio materials are traditionally cultured in two dimensions in biology, but cells in the body are in three dimensions," he says.

"So if you want cells to do everything that they're meant to do in the body, then they have to be arranged in three dimension in the lab, just as they are in the body.

Alan Faulkner-Jones with the bio printer he built himself. He says printing functional human liver tissue for drug testing is probably some way off

"This machine enables you to deposit cells inside a three dimensional structure as you print it. In the same way that standard 3D printing works, it works on a layer by layer process, it uses two different liquids that when put together form a gel matrix [which can hold cells]."

The aim eventually is to print a 3D liver micro-tissue - an organ on a chip, external.

This would respond in the same way as a whole liver, but on a much smaller scale for testing drugs.

Ideally, a model system of an entire human body is the goal - a human body on a chip. The purpose of this would be to reduce reliance on and possibly ultimately replace animal testing.

This all lies some way off.

But even if we never really take to the idea of having 3D printers sitting at home, or if it fails to change the face of manufacturing as some are predicting, technology that could potentially produce a functioning kidney built from your own cells - or help reconstruct the face of a car crash victim - isn't going anywhere anytime soon.

An adjustable - and beautiful - brace for scoliosis by US company 3D Systems. Deenie would have approved.

3D printing lets artists create unique pieces - that can be replicated if need be

3D printed fashion accessories

Printed mask