The death of the weekly supermarket shop

- Published

- comments

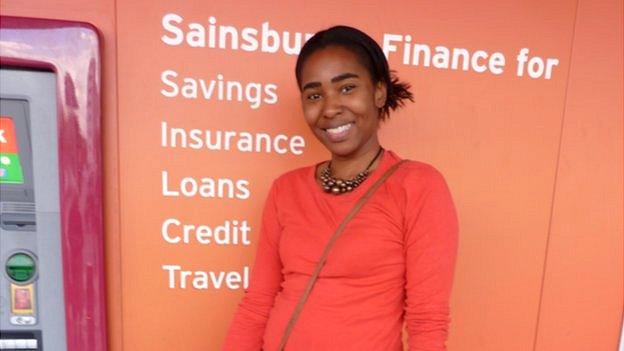

Gaynor Francis says the vast choice in big supermarkets can be overwhelming

"I tend to avoid the big stores as there's so much choice and they're very busy," says Gaynor Francis, a 37-year-old working mum of two.

She does an online shop once a month, which she supplements with weekly top-up shops, typically at convenience stores, for essentials such as fresh fruit and veg and milk.

Today she's doing a rare top-up shop at the Sainsbury's Sydenham superstore, a hypermarket in south-east London, but she hasn't enjoyed it and has ended up spending more than she intended.

"I want to go in and out and I get distracted by the people and the choice, it's just overwhelming," she tells me.

Like many urban areas, competitors to the Sydenham store are not far away. Just five minutes away on foot there's a Lidl, or if you turn the other way a Tesco Express.

It's this kind of proximity to rivals that has helped fuel the dramatic change in shopping habits. New Sainsbury's boss Mike Coupe said the industry had "changed beyond all recognition", with "customers shopping very differently to the way they were shopping even a year ago".

Segmented shopping

These changes, experienced by all the "Big Four" supermarkets, suggest that the era of the once-a-week big shop is nearing an end. People are tending to buy less but are shopping more frequently and have "segmented" their shopping, buying items from different places based on either price or convenience.

Tony Middleton shops around for the best deals

Shoppers now visit four different grocery stores a month on average, external, with almost half of them visiting two stores on the same trip, according to food research firm IGD.

Tony Middleton, a 44-year-old father of one, is a prime example. He's arrived at Sainsbury's via Lidl, where he goes almost daily.

"I go to Lidl first, and then if they haven't got the right stuff I come here," he says. He does a weekly essentials shop at the hypermarket, but says the food in Lidl is "cheaper and tastes better", particularly the bread, fruit and vegetables.

The 2008 financial crisis and consequent recession, which forced "middle England" to change their shopping habits to save money, has driven much of this shift, according to Shore Capital analyst Clive Black.

"People who don't have any money have always shopped week to week, but in the last five years, with wages compressed, middle England has had to find money and that has changed the way they shop."

Despite the economy improving, the habit of shopping little and often has stuck.

Analysts attribute this to a variety of reasons, including the desire to cook fresh food from scratch, the nascent rise in popularity of specialised foods such as artisan breads and craft beers, not wanting to waste food by throwing it away and, of course, time.

While much has been made of the impact of online shopping, it still accounts for just 4.4% of total sales in the year to April, according to IGD, which expects it to reach 8.3% of all sales by 2019.

It's the convenience sector that has been the biggest beneficiary of the change in shopping habits. IGD found shoppers used convenience stores more than any other type of store format, and expects the sector to account for nearly a quarter of all food and grocery sales by 2019.

'Promiscuous behaviour'

"Shoppers now expect grocery retailing to organise itself around their lives rather than building their routines around store opening hours. They expect to buy whatever they want, any time, any place in the most convenient way to them," says IGD chief executive Joanne Denney-Finch.

What's more, this "small promiscuous behaviour at the end of the road" has dramatically changed brand loyalty, says Ben Perkins, head of consumer research at accountancy firm Deloitte. People now shop from a variety of different brands and no longer identify themselves as, say, a "Tesco" or a "Sainsbury's" shopper.

"There's now a whole generation of people who have never shopped in a supermarket on a Saturday, never known a world without the internet. They are the families of tomorrow."

Mr Perkins says there is "little chance" that once this generation reaches a certain age, and has its own children, that its behaviour will change.

But age is not the only demographic at play. There has also been a steady increase in the number of single people, now accounting for 7.7 million households and the second most common type of living arrangement, according to the Office for National Statistics.

'I know where everything is'

Kiran Garcha likes the convenience of Sainsbury's Local during the week

Forty-year-old primary school teacher Kiran Garcha, who lives in London's Hatton Cross, falls into this category.

She does a once-a-month shop at a large Tesco, but then visits her Sainsbury's Local in between.

"I pop in quite often, probably around twice a week, often on my way home from work. It's half a mile down the road, there's free parking right outside and there's never much of a queue. Because it's small I know exactly where everything is and can pick it up easily," she tells me.

The supermarkets have ramped up their expansion of the format accordingly. Both Sainsbury's and Tesco now have more convenience stores than supermarkets, while Morrisons and Asda are also investing significantly in the sector.

Yet it's still only a tiny part of their sales, less than 8% of total sales in the case of Sainsbury's.

Collapse on the cards?

Veteran retailer Bill Grimsey, a former chief executive of DIY store Wickes and Iceland, who has already written a report on how to improve the High Street, believes the prognosis is grim.

"In the next five to 10 years one of the Big Four could disappear. It's not beyond the bounds of possibility," he says, pointing to the demise of the once mighty 800-store Woolworths as an example.

Yet even the most pessimistic analysts believe this is unlikely. IGD predicts that less money will be spent at superstores and hypermarkets by 2019, but still expects them to represent 35% of the total grocery market.

The stores will also help to service the rising shift to online and click-and-collect orders

And as Planet Retail analyst David Gray points out, the supermarkets are still making profits, most of which come from their big stores, just less than previously.

"The headline numbers look bad. But even if sales are going backward, they're still profitable and there's still a value to that."

- Published1 October 2014

- Published1 October 2014

- Published22 April 2015

- Published9 September 2013