Belgian comic books turn over a new page

- Published

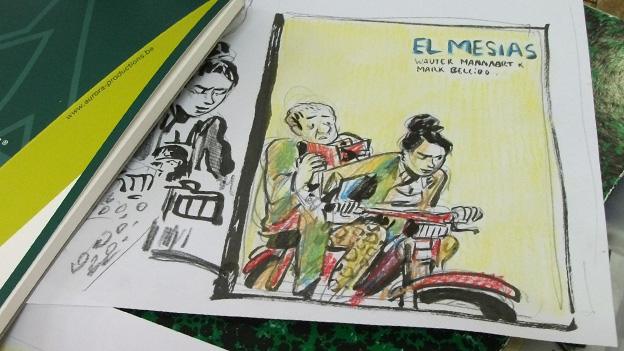

For L'Employé Du Moi, staying small is the key to survival

At an artists' studio in a run-down part of Brussels, the next chapter in Belgium's rich comic-book history is being sketched out.

For the country that gave the world Tintin and the Smurfs, comic art - or "bande dessinée", to give it its French name - is a serious business.

But like the music industry and other kinds of publishing, the comics world is undergoing rapid technological change that has turned its old certainties upside down.

And at small start-up firm L'Employé Du Moi, the challenge is to take the "ninth art" into the 21st Century.

A handful of artists work at the firm's premises in the north of the Belgian capital, literally just across the tracks from the red-light district.

Max de Radigues and Sacha Goerg are part of the editorial board of L'Employé Du Moi, which they started with friends in 2000 after leaving art school. Since then, it has published more than 70 hardback comic books, most of them in the graphic novel category.

L'Employé Du Moi features artists from outside the mainstream of Belgian comics

They are proud that their comics come in different sizes and styles, something that sets them apart from the mainstream.

"With Tintin books, they're all 62 pages and they're all in colour," says Mr de Radigues. "We try to make the perfect fit for each book - what size should it be, what kind of paper."

None of the artists is paid a salary, but they receive part of the proceeds from the sales of their comic books.

"We try to make enough money back to make new books," says Mr Goerg. "We're a small company and right now, I think we want to stay that way. It's really difficult to get up the ladder and to produce more money, we would have to be much bigger."

The Hergé Museum first opened on 22 May 2009, on what would have been Hergé's 102nd birthday

While new generations of artists are fighting to make their mark, Belgium's comic art heritage is part of the country's cultural mainstream.

But strangely enough, the best-known Belgian comic-book character, Tintin, is now in the hands of a Swiss-based Englishman, Nick Rodwell.

Mr Rodwell became the head of Moulinsart, the company that manages the Tintin empire, when he married the widow of the boy reporter's creator, Hergé.

His tight control over the Tintin legacy has proved controversial with some fans. But it has spawned a popular tourist attraction in the shape of the Hergé Museum, an hour out of Brussels in the town of Louvain-La-Neuve.

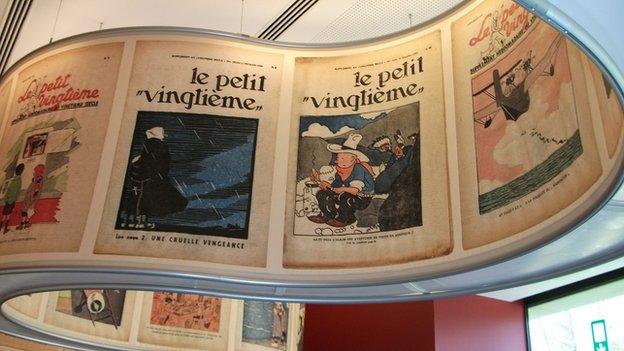

Herge began drawing Tintin for this Belgian newspaper supplement

Museum administrator Robert Vangeneberg says the museum is visited by 80,000 people a year. Visitor numbers surged by 20% after Steven Spielberg's Tintin film came out in 2011, but the effect was short-lived.

"In budgetary terms, it ought to be 150,000 a year, but fortunately, we have other sources of revenue," he says.

These include sales from the gift shop, on-site restaurant Le Petit Vingtième and various business events. The museum can be hired by companies for private visits, conferences, dinners and cocktail parties, while comic art symposiums are organised in conjunction with the neighbouring university.

For Mr Vangeneberg, the museum bears witness not only to Herge's talents as a creator of comic books, but also as "a powerful observer of his era".

He sees Hergé's work as reflecting the man's insights into human behaviour, as well as the environmental and socio-economic context of the age in which it was produced.

But the Hergé Museum is not the only place to appreciate the depth of Belgium's comic-strip culture. The genre has its own dedicated centre in the heart of Brussels, the Comics Art Museum, which celebrated its 25th anniversary earlier this month.

The Belgium comics museum is expanding, opening a new centre in France, says the BBC's Tim Allman

The museum's communications director, Willem De Graeve, says the comics business has seen great changes in the past quarter-century since the museum opened, originally as the Belgian Comic Strip Centre.

"It's a huge difference," he says. "In 1989, there were 500 new comic books. Last year, there were 5,000."

At the same time, the museum's own audience has changed. "When we opened, almost 80% of people coming here were Belgians. Now it's the other way round. Belgians are a minority, only 17%."

Part of the reason for that is the advent of low-cost airlines and high-speed rail services, including the Eurostar, that have made Brussels more easily accessible for tourists.

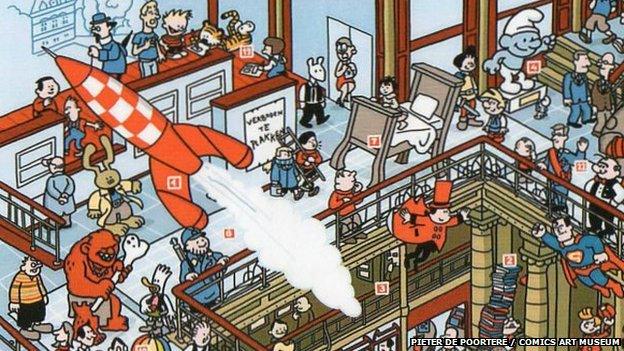

Pieter De Poortere drew a special homage to mark the Comics Art Museum's 25th anniversary

At the same time, rather than being the preserve of a cult audience, the comics museum has become part of that mass-market tourist trail, an essential part of Belgium's international image.

"Twenty-five years ago, people coming here were comics fans or people who knew comics," says Mr De Graeve. "Now the majority don't know anything about comics. We're some kind of exotic museum to them.

"It's like when you go to Scotland, you go to a whisky distillery. Does that mean that you're a whisky fan?"

As part of the anniversary celebrations, the museum has added two new permanent exhibitions: one devoted to the Smurfs and one to a newer star of Belgian comics, Pieter De Poortere, who began publishing the adventures of his character Boerke in 2001.

Pieter De Poortere is seen as a Flemish-language cartoonist, but his works have no speech bubbles

According to Mr De Poortere, the internet has had the same disruptive effect on his art form as on the record industry: the hardback comic books known in the trade as "albums" sell only about a fifth as many copies as they did in the 1980s.

"Back then, if you had a big publisher, you were set for life," he says. "Now everybody expects everything for free.

"But I think that's mainly a problem for the editors. As an artist, I think it's a much more interesting time.

"I have an agent that searches for clients and they come from everywhere. I get to do exhibitions in Toulouse or Moscow or Spain.

"There are computer games, children's books. If you're a bit open-minded, it's a lot of fun. I'm glad I'm doing this now and not 25 years ago."

- Published11 October 2014

- Published13 March 2014

- Published24 October 2011

- Published23 June 2011