Health tech: When does an app need regulating?

- Published

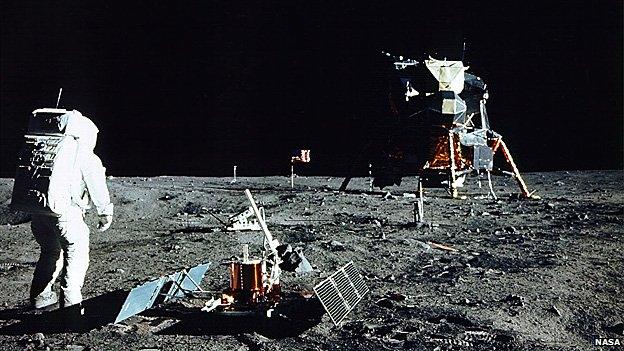

Simpler times: The smartphone in your pocket is more powerful than all the tech put together on the Apollo 8

There was a time - almost forgotten now - when your phone was something you simply made calls on.

These days you've got more computing power in your pocket than was available to astronauts on the Apollo 8 as it headed for the moon in 1969.

Among the many things your phone can do, apparently, is look after your health.

Apple's new Healthkit has punctuated the fact that this tech has gone mainstream. You can measure steps, calories, and heart rate, and this is just for starters.

Kickstarter and Indiegogo are filled with devices - many seemingly trying to avoid the longer road last week's Portuguese start-ups have taken to get their devices certified, by adding a disclaimer in the small print - 'this is not intended to be used as a medical device'. But is that enough?

Where does the line between glorified pedometer and healthcare technology lie?

If you found yourself pressing your smartphone to your face in the belief that the light waves from the app would cure your acne you're probably already familiar with the problem.

And the makers of those (absolutely useless) apps were subsequently fined, external.

So I asked three lawyers for their take on what makes something a medical device - and what you should be doing if your brand new app is one - whether using the CE mark in the EU, or complying with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines in the US.

Apple's Healthkit (second left) not only tracks steps and calorie intake etc, it can also integrate with other apps and wearable technology devices

Beverley Flynn, Stevens & Bolton

Putting a disclaimer that your product is not a medical device is simply not effective [if it is used for patient treatment.]

If it is a medical device you have to register [in the UK] with the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), external [or their equivalent in other EU countries]. [The law] all stems from an EU Directive.

Sometimes you have to provide them with clinical data, and there is a post surveillance obligation. If there is an adverse reaction, then you have to report that and keep in place reporting procedures.

The obligation to decide whether or not it is a medical device falls on the manufacturers.

When is an app a medical device?

A medical device is 'any instrument, apparatus, appliance, software, material or other articles, whether used alone or in combination, including the software intended by its manufacturer to be used specifically for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes and necessary for its proper application intended by the manufacturer to be used for human beings for the purpose of:

diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of disease;

diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of or compensation for an injury or handicap;

investigation, replacement or modification of the anatomy or of a physiological process;

control of contraception;

and which does not achieve its principal intended action in or on the human body by pharmacological, immunological or metabolic means, but which may be assisted in its function by such means.'

MHRA guidance

So, if you are a company that commissioned a developer to prepare an app for you, and if you have the idea for the app and it is going to go on the market in your name, then you are the manufacturer for the purposes of the legislation, not the developer themselves.

They have to have a medical purpose (see the box).

When you get new technologies such as the bands on your arm, where you just input your information… [so] you know much exercise you have done, how much food that you have eaten that week, it is not actually telling you what to do as a result.

That is unlikely to be a medical device.

Beverly Flynn: "Funders are going to want the comfort that you've actually addressed the regulatory framework correctly".

But if it is something that actually supports decision-making, where it told you it is time to take your next piece of medicine, or it is calculating what your heart rhythm is - that's more likely to be.

It can go to the value of the investment, when other investors come in and they find it to be a medical device, that needs to be registered, and it can also [affect the company's reputation].

Once you have a device CE marked in one country, it does enable you to pass the medical device around the EU relatively simply. Getting the CE mark is like your passport to the rest of the European Union.

[In the event that something goes wrong] the fact that you haven't registered correctly will show that you haven't putting in place the appropriate systems.

If you haven't followed the processes applicable to a medical device, then it will be more difficult to argue any defence on the product liability side, because you certainly haven't followed the correct steps.

Ed Vickers, Taylor Wessing

There is European legislation that governs all of this and which sets out what a medical device is.

Ed Vickers: "Apps with CE marking are not numerous on the app stores"

What's important is, whether the software has a medical purpose of some sort.

So that might be to help with diagnosis of a disease or monitoring of a disease or treatment of a disease in some way.

And as you can imagine, there is lots of potential for grey areas.

When you see a device with a CE mark on it, you should be able to comfort yourself with the thought that they have demonstrated that it is sufficiently safe, and meets all of the quality criteria that the legislation provides for.

If it doesn't meet the criteria, it is not allowed to be put on the market until you have got it CE marked.

If you should have one, and it comes to the attention of the relevant authorities, they can require you come off the market, and take steps to remove your medical device from the chains of commerce.

There are apps that are essentially just medical dictionaries. And that's just simply presenting information, it is not processing any specific data about a particular patient, so generally speaking you wouldn't consider those to be within the regulatory framework of medical devices.

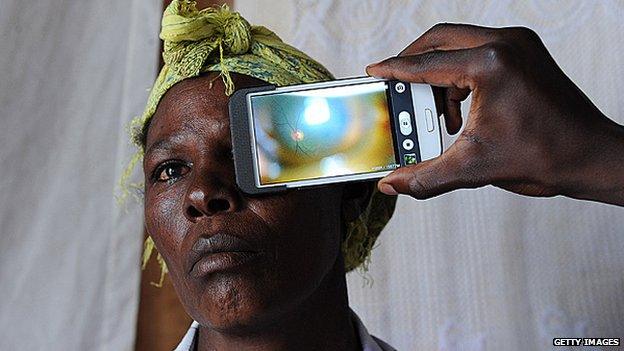

Healthcare apps aimed at the developing world have proved revolutionary, like this app for checking eye health

It is really once you start to take in data from a particular patient and then do something with it, in order to make some recommendation or to give a doctor the ability to make some kind of diagnosis, that you get closer to the border line.

An example might be putting a patient's height and weight into an app and generating a body mass index.

That is close to the borderline, and you might imagine that is probably just the right side of the border line.

Once you do a bit more complicated analysis perhaps, and particularly if it is in order to aid a doctor in making a diagnosis or a choice about a treatment, then that sort of processing is falling probably on the other side of the dividing line, and will be considered to be a medical device.

There are pros and cons to taking either approach. The benefits to being a medical device and having a CE mark [are] it is sort of badge of security, and you can be comforted that you will be able to market your product throughout Europe.

On the other side, if you don't want to have to jump through those regulatory hoops, keep yourself on the right side of the dividing line.

Neil O'Flaherty, OFW Law

In the US, the FDA regulates medical devices.

There's not a new law [but] what the FDA has done is issued a guidance document which basically provides their interpretation of how they want to apply existing US laws to mobile medical apps.

Neil O'Flaherty is seeing more and more clients who need advice on medical health apps

What does the FDA consider to be a mobile medical app that they want to regulate?

Well, the first thing is that it meets the definition of a "device" under the Federal Food and Drug and Cosmetic Act. (See box)

Then the next question is, is the app acting as an accessory to a traditionally-regulated medical device, or is it transforming a mobile platform like your smartphone into what would be a traditionally-regulated medical device.

For instance, allow you to use your smartphone as a thermometer, or as a blood glucose reader.

If you fall in the mobile medical app category, what the FDA is doing, is setting up criteria by which they apply already-existing medical device controls to various categories of mobile medical apps, depending on their characteristics and what they do.

Definition of a medical device - Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

A "device" is "an instrument, apparatus, implement, machine, contrivance, implant, in vitro reagent, or other similar or related article, including a component part, or accessory which is -

•recognized in the official National Formulary, or the United States Pharmacopoeia, or any supplement to them,

•intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, in man or other animals, or

•intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals, and which does not achieve any of its primary intended purposes through chemical action within or on the body of man or other animals and which is not dependent upon being metabolized for the achievement of any of its primary intended purposes."

Some have more regulation than others, but it's all based on already-existing regulatory controls for medical devices.

If you are a regulated mobile medical app, then all of a sudden in the FDA's eyes you become a traditional medical device manufacturer, with the obligations that go along with that.

For instance, let's say your app requires you to go to the FDA and get a marketing authorisation, a lot of devices in the US that need marketing authorisation go through something known as the 510(k) submission process.

So, let's assume that applies to you, and you don't bother to do that 510(k) submission process, you don't get a 510(k) clearance from the FDA, you are marketing your product in the US, that then opens up the various enforcement tools.

Tablets and smartphones are becoming more and more common in healthcare facilities

If your device is misbranded for instance, the agency can say: well, under our laws, it's illegal for you to ship in interstate commerce a misbranded medical device.

And so… not fulfilling your requirements opens you up to the FDA taking enforcement action against you. It depends also what the public health risk involved is.

[Getting FDA approval is a long process] - the most stringent is known as the premarket approval process or PMA process, for the highest risk devices which is Class III here in the U.S.

You basically have to independently demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of your product. The vast majority of devices that require some type of FDA marketing authorisation go through that 510(k) process I referred to before.

If you're talking of a PMA, you know you can be looking at approximately two years from start to finish.

A 510(k)s, you can easily be looking at six months.

By not doing things the right way from an FDA regulatory perspective, I think you set yourself up for vulnerabilities down the road, if you end up in product liability litigation because it will be easy for a plaintiff's attorney to make an argument that it's negligence.

In my experience, most people out there want to do the right thing.

They either don't understand that there is some regulatory scheme that applies to their product, or they realise there is a regulatory scheme but they just don't have the background to appreciate the significance and ramifications of what they need to do.