Ebola: Can big data analytics help contain its spread?

- Published

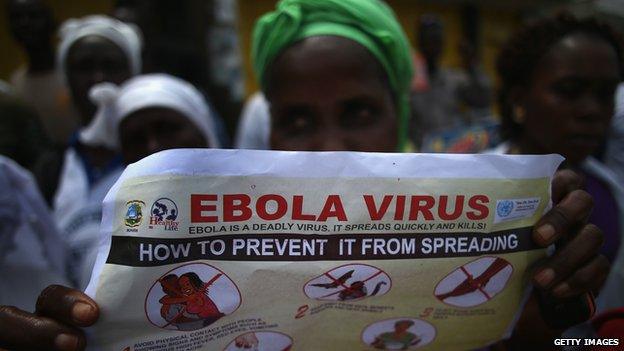

Educating the public about how the virus is spread is a key challenge for health professionals

The Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa has now claimed more than 4,000 lives.

While emergency response teams, medical charities and non-governmental organisations struggle to contain the virus, could big data analytics help?

A growing number of data scientists believe so.

Mobile mapping

Mobile phones, widely owned in even the poorest countries in Africa, are proving to be a rich source of data in a region where other reliable sources are sorely lacking.

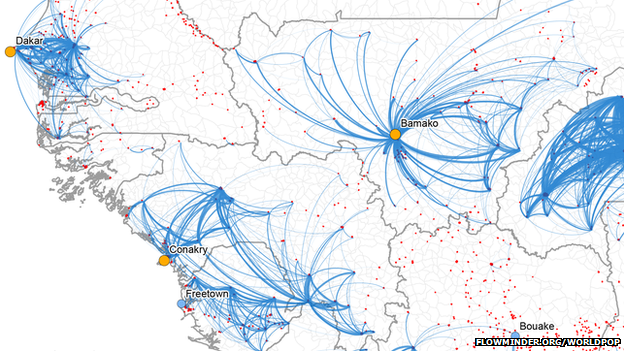

Orange Telecom in Senegal handed over anonymised voice and text data from 150,000 mobile phones to Flowminder, a Swedish non-profit organisation, which was then able to draw up detailed maps of typical population movements in the region.

Authorities could then see where the best places were to set up treatment centres, and more controversially, the most effective ways to restrict travel in an attempt to contain the disease.

The drawback with this data was that it was historic, when authorities really need to be able to map movements in real time. People's movements tend to change during an epidemic.

This is why the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is also collecting mobile phone mast activity data from mobile operators and mapping where calls to helplines are mostly coming from.

Mobile phone data from West Africa is being used to map population movements and predict how the Ebola virus might spread

A sharp increase in calls to a helpline from one particular area would suggest an outbreak and alert authorities to direct more resources there.

Mapping software company Esri is helping CDC to visualise this data and overlay other existing sources of data from censuses to build up a richer picture.

The level of activity at each mobile phone mast also gives a kind of heatmap of where people are and crucially, where and how far they are moving.

"We've never had this large-scale, anonymised mobile phone data before as a species," says Nuria Oliver, a scientific director at mobile phone company Telefonica.

"The most positive impact we can have is to help emergency relief organisations and governments anticipate how a disease is likely to spread.

"Until now they had to rely on anecdotal information, on-the-ground surveys, police and hospital reports."

Mobile phones are also proving to be a useful ideal way to convey health messages.

Cholera lessons

This kind of phone data analysis has already been successfully applied to other health crises.

For example, in 2010, after the Haiti earthquake, a joint research team from Karolinska Institute in Sweden and Columbia University in the US analysed calling data from two million mobile phones on the Digicel Haiti network.

Digicel mobile data was used to track population movements following the Haiti earthquake disaster in 2009

This enabled the United Nations and other humanitarian agencies to understand population movements during the relief operations and during the subsequent cholera outbreak, meaning they could allocate resources more efficiently and identify areas at increased risk of new cholera outbreaks.

Analysis of the data from 15 million phones is also being used to map and predict the spread of malaria in Kenya.

But Ms Oliver admits: "This mobile data can only ever give us a partial picture of what is going on."

Effective measures?

To get a fuller picture, we need more sources of data and the ability to analyse them quickly, experts say.

"Big data analytics is about bringing together many different data sources and mining them to find patterns," says Frances Dare, managing director of Accenture Health.

"We have health clinic and physician reports, media reports, comment on social media, information from public health workers on the ground, transactional data from retailers and pharmacies, travel ticket purchases, helpline data, as well as geo-spatial tracking."

The British hospital ship RFA Argus prepares to take supplies to Sierra Leone

Such analysis can also be used to measure whether containment policies, education campaigns and treatments are working, argues Peder Jungck, chief technology officer for BAE Systems' intelligence and security division.

"For example, doctors can see what percentage of a population is taking the proper precautions to minimise the spread of the disease and what percentage is disregarding that notice by analysing big data sets such as social media amongst high-risk populations," he says.

"In the case of Ebola, analysts studying big data sets could also analyse potential sanitation challenges and whether regional environmental factors such as weather could impact the rate at which the disease is spread."

Cross-border spread

In the age of international travel it is much easier for diseases to spread abroad, particularly when they have an incubation period of up to 21 days, like Ebola.

Europe and the US are consequently on high alert and implementing screening at some airports.

But at least in the digital age, tracking the movement of potentially infected people is a lot easier.

"Port, train and flight data, as well as number plate recognition, can all help track potentially infected people and identify who they may have come into contact with," says David Bolton, head of healthcare at big data analytics company Qlik, which has developed an Ebola-tracking app.

On Tuesday Heathrow Airport began screening some passengers for symptoms of the Ebola virus

Social trends

Analysts are also getting better at spotting trends from social media and search engine activity.

While Google Flu Trends, which tries to predict likely flu outbreaks based on how often people use key search terms, has been shown to be inaccurate at times, other methods that make use of a much wider range of data sets, are enjoying more success.

For example, business consultancy Accenture, big data specialist SAS and the US University of North Carolina say they predicted the US 2012-13 flu season three months before CDC issued its official warning.

"By analysing social media, such as blogs, online forums and Twitter, we can find early warning signs of health events," says Accenture's Frances Dare.

"We narrowed down the number of key words indicating flu symptoms to 152, mapped where these words were being used, and predicted a flu outbreak about two months before the official data in 2013."

Finding a cure?

Tim Gamble, principal consultant at Datamonitor Healthcare, believes big data analytics will also prove essential to understanding the genetics of the virus, why some strains are more deadly, and why some people seem to be more resistant to it than others.

He used to work for US pharmaceutical company Pfizer specialising in infectious diseases.

"Anti-retroviral treatment for HIV didn't really take off until many people started to die from AIDS. I worked on Pfizer's HIV product and we found that some populations in Scandinavia had more resistance to the disease than others.

.jpg)

The Ebola virus is particularly contagious and is spread via infected blood, vomit and faeces

"We were then able to develop a drug that mimicked the way those people resisted the disease," he says.

The same approach could be applied to the Ebola virus, he believes.

In short, big data analytics is being brought to bear at all levels to combat the spread of Ebola.

But as Qlik's David Bolton admits: "We're learning all this from scratch - we've never had this level of data before.

"So it's probably too early to say whether big data analytics is having a meaningful impact on the rate and spread of the disease, but at least it is helping us decide where to allocate our resources."