Falling oil prices: Who are the winners and losers?

- Published

A woman walks past a board listing currency exchange rates in Moscow

Global oil prices have fallen sharply over the past seven months, leading to significant revenue shortfalls in many energy exporting nations, while consumers in many importing countries are likely to have to pay less to heat their homes or drive their cars.

From 2010 until mid-2014, world oil prices had been fairly stable, at around $110 a barrel. But since June prices have more than halved. Brent crude oil has now dipped below $50 a barrel for the first time since May 2009 and US crude is down to below $48 a barrel.

The reasons for this change are twofold - weak demand in many countries due to insipid economic growth, coupled with surging US production.

Added to this is the fact that the oil cartel Opec is determined not to cut production as a way to prop up prices.

So who are some of the winners and losers?

Russia: Propping up the rouble

The falling rouble and plunging oil revenue are some of President Putin's biggest challenges

Russia is one of the world's largest oil producers, and its dramatic interest rate hike to 17% in support of its troubled rouble underscores how heavily its economy depends on energy revenues, with oil and gas accounting for 70% of export incomes.

Russia loses about $2bn in revenues for every dollar fall in the oil price, and the World Bank has warned that Russia's economy would shrink by at least 0.7% in 2015 if oil prices do not recover.

Despite this, Russia has confirmed it will not cut production to shore up oil prices.

"If we cut, the importer countries will increase their production and this will mean a loss of our niche market," said Energy Minister Alexander Novak.

Falling oil prices, coupled with western sanctions over Russia's support for separatists in eastern Ukraine have hit the country hard.

The government has cut its growth forecast for 2015, predicting that the economy will sink into recession.

Former finance minister, Alexei Kudrin, said the currency's fall was not just a reaction to lower oil prices and western sanctions, "but also [a show of] distrust to the economic policies of the government".

Given the pressures facing Moscow now, some economists expect further measures to shore up the currency.

"We think capital controls as a policy measure cannot be off the table now," said Luis Costa, a senior analyst at Citi.

Russia's economy is forecast to fall into recession in 2015 if oil prices do not regain ground

While President Putin is not using the word "crisis", Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev has been more forthright on Russia's economic problems.

"Frankly, we, strictly speaking, have not fully recovered from the crisis of 2008," he said in a recent interview.

Because of the twin impact of falling oil prices and sanctions, he said the government had had to cut spending. "We had to abandon a number of programmes and make certain sacrifices."

Russia's interest rate rise may also bring its own problems, as high rates can choke economic growth by making it harder for businesses to borrow and spend.

Venezuela: No subsidy cuts

Venezuela saw mass anti-government protests earlier this year

Venezuela is one of the world's largest oil exporters, but thanks to economic mismanagement it was already finding it difficult to pay its way even before the oil price started falling.

Inflation is running at about 60% and the economy is teetering on the brink of recession. The need for spending cuts is clear, but the government faces difficult choices.

The country already has some of the world's cheapest petrol prices - fuel subsidies cost Caracas about $12.5bn a year - but President Maduro has ruled out subsidy cuts and higher petrol prices.

"I've considered as head of state, that the moment has not arrived," he said. "There's no rush, we're not going to throw more gasoline on the fire that already exists with speculation and induced inflation."

The government's caution is understandable. A petrol price rise in 1989 saw widespread riots that left hundreds dead.

Saudi Arabia: Price versus market share

Saudi Arabia is not expected to cut production to prop up oil prices in the short term

Saudi Arabia, the world's largest oil exporter and Opec's most influential member, could support global oil prices by cutting back its own production, but there is little sign it wants to do this.

There could be two reasons - to try to instil some discipline among fellow Opec oil producers, and perhaps to put the US's burgeoning shale oil and gas industry under pressure.

Although Saudi Arabia needs oil prices to be around $85 in the longer term, it has deep pockets with a reserve fund of some $700bn - so can withstand lower prices for some time.

"In terms of production and pricing of oil by Middle East producers, they are beginning to recognise the challenge of US production," says Robin Mills, Manaar Energy's head of consulting.

If a period of lower prices were to force some higher cost producers to shut down, then Riyadh might hope to pick up market share in the longer run.

However, there is also recent history behind Riyadh's unwillingness to cut production. In the 1980s the country did cut production significantly in a bid to boost prices, but it had little effect and it also badly affected the Saudi economy.

Opec: Not all are equal

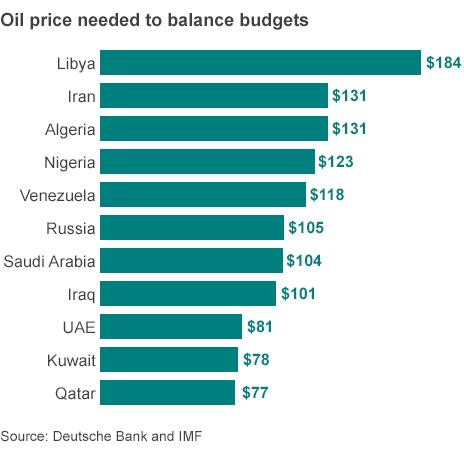

Some Opec members need oil to be above $120 a barrel to avoid hard spending choices

Alongside Saudi Arabia, Gulf producers such as the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait have also amassed considerable foreign currency reserves, which means that they could run deficits for several years if necessary.

Other Opec members such as Iran, Iraq and Nigeria, with greater domestic budgetary demands because of their large population sizes in relation to their oil revenues, have less room for manoeuvre.

They have combined foreign currency reserves of less than $200bn, and are already under pressure from increased US competition.

Nigeria, which is Africa's biggest oil producer, has seen growth in the rest of its economy but despite this it remains heavily oil-dependent. Energy sales account for up to 80% of all government revenue and more than 90% of the country's exports.

The war in Syria and Iraq has also seen Isis, or Islamic State, capturing oil wells. It is estimated it is making about $3m a day through black market sales - and undercutting market prices by selling at a significant discount - around $30-60 a barrel.

United States: Fracking boom

US domestic oil production has boomed due to fracking

"The growth of oil production in North America, particularly in the US, has been staggering," says Columbia University's Jason Bordoff.

Speaking to BBC World Service's World Business Report, he said that US oil production levels were at their highest in almost 30 years.

It has been this growth in US energy production, where gas and oil is extracted from shale formations using hydraulic fracturing or fracking, that has been one of the main drivers of lower oil prices.

"Shale has essentially severed the linkage between geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East, and oil price and equities," says Seth Kleinman, head of energy strategy at Citi.

Even though many US shale oil producers have far higher costs than conventional rivals, many need to carry on pumping to generate at least some revenue stream to pay off debts and other costs.

Europe and Asia: Mixed blessings

Growth in the European Union remains weak

With Europe's flagging economies characterised by low inflation and weak growth, any benefits of lower prices would be welcomed by beleaguered governments.

A 10% fall in oil prices should lead to a 0.1% increase in economic output, say some. In general consumers benefit through lower energy prices, but eventually low oil prices do erode the conditions that brought them about.

China, which is set to become the largest net importer of oil, should gain from falling prices. However, lower oil prices won't fully offset the far wider effects of a slowing economy.

Japan imports nearly all of the oil it uses. But lower prices are a mixed blessing because high energy prices had helped to push inflation higher, which has been a key part of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's growth strategy to combat deflation.

India imports 75% of its oil, and analysts say falling oil prices will ease its current account deficit. At the same time, the cost of India's fuel subsidies could fall by $2.5bn this year - but only if oil prices stay low.