Is Europe's economic motor finally stalling?

- Published

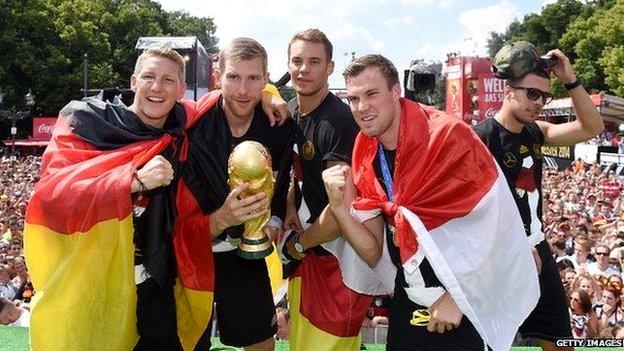

It all started at the end of the summer. Germany had just won the World Cup. And the country's powerful economy felt like it was steaming ahead. The country was on a high.

But then, suddenly, a survey came out showing that German business leaders were less than optimistic about the future. More negative figures soon followed: falling exports, jittery investors and a slump in industrial production.

And earlier this week the negativity became official, as Germany's government downgraded its forecast for economic growth for this year, from 1.8% to 1.2%.

So is Europe's economic motor about to stall?

You wouldn't think so on the streets of Berlin.

Buildings are shooting up. Cafes and shops are packed. And it's hard to believe that just ten years ago Germany was known as the sick man of Europe. The country feels like it is booming.

Chatting to customers shopping in a busy bookshop on Friedrichstrasse in the centre of Berlin, it is impossible to find anyone who believes Germany's economy is doing badly.

"Compared to other countries, Germany is doing very well," says Falco, a 27-year-old sales account manager.

.jpg)

Many Germans don't feel their country's economy is stalling

Controversial question

The headlines are negative - particularly in the international press. But the mood at home in Germany remains surprisingly positive.

In fact according to government figures, domestic consumption is up, with small retailers recording a three-year high in August.

Even many business leaders, despite falling exports, say things are not as bad as the headlines suggest.

"The figures are difficult, but businesses are generally optimistic about the economy and the sentiment is really not that bad," one member of an association of German business leaders tells me.

Rosemarie Schroeter says she's worried about growing gap between rich and poor.

She asks to remain anonymous - because the question of whether Germany is tipping into recession has become so controversial, she says.

So what's the explanation behind this disparity between the negative statistics and the relatively positive mood?

The macroeconomic figures may look bad. But Germany's labour market looks very good indeed. Unemployment is less than 5%. Inflation is low, at less than 1%.

And after years of austerity and low wages, take-home pay is starting to rise. Wages are expected to go up this year by around 3%. So many consumers are feeling better off than they have done for years.

Low investment rate

Nevertheless there is a growing unease among many Germans about what the future may hold.

Back at the bookshop I meet retired teacher Rosemarie Schroeter, as she looks at novels laid out on a table with a friend.

"Personally my situation is good, and all the people I know are satisfied.

"But I'm pessimistic about the way things are going, and the growing gap between rich and poor. We were chatting about that just now."

When you talk to people in Germany, again and again they echo this thought - that they personally are doing fine right now, but are concerned about the future.

Marcel Fratzscher believes they are right to be worried.

Professor Fratzscher is president of the economic think-tank DIW Berlin, and is one of many German economists who are calling on the German government to start spending more on infrastructure.

Germany has one of Europe's lowest investment rates, and low investment means low future growth.

According to Mr Fratzscher, the country needs to spend an additional 10bn euros a year - that's £8bn - simply to maintain roads, bridges and public transport in their current state.

He estimates that there is a 30% probability of the economy contracting again in the next quarter - which would technically put Germany into a recession.

"Germany has this illusion that the current economic weakness is because of our naughty neighbours - that they are not doing the right reforms," he says.

And certainly that was the reason given by Sigmar Gabriel, Germany's Economy Minister, when asked to explain the government's decision to downgrade the economic forecast.

"The German economy is steering through rough foreign waters," he told reporters earlier this week.

Germany has one of Europe's lowest investment rates

Budget debate

The crisis in the rest of the EU has hit exports. And German manufacturers with close trade links to Eastern Europe have been hit hard by the Ukraine crisis and the Western sanctions against Russia.

But now a fierce debate is growing over whether the government is also to blame for what critics see as an obsession with balancing the books.

Next year Angela Merkel's government wants to avoid taking on new government debt for the first time since 1969.

The policy is known as "die schwarze Null", or the "black zero", and it's become a key symbol of her government's success - proof of budget discipline, and a sign of moral rectitude.

Critics say Germany should start spending its way back to strong growth. And that it makes no sense to cut the deficit when interest rates are so low, and borrowing so cheap.

But Berlin sees over-spending and over-borrowing as the root cause for the EU's economic problems in the first place.

And the government feels vindicated by Germany's own strong economic performance: having pushed through its own painful reforms over the last decade, Germany came out the other side as Europe's strongest economy - at least for now.

- Published16 October 2014

- Published14 October 2014

- Published9 October 2014