What can be done to save the High Street?

- Published

Part of Colliers Wood High Street today, typical of many in south London

What can be done to improve my local High Street in Colliers Wood in south London?

It is a down-at-heel south London main road, choked with commuter traffic in the morning and evening.

The cars drive past a parade of fast food outlets, estate agents and several empty shops.

Some businesses have been there a long time, more than 40 years in the case of Burge and Gunson, a large plumbing merchant and bathroom store.

Some more recent shops have established themselves in the past 10 years or so, such as Moose Cycles.

But many others have come and gone with a seemingly tenuous grip on commercial life.

And this year the Provenance pub, which opened as the Red Lion in the early 1800s, finally closed down after struggling for years.

At the bottom of the High Street though, something is stirring.

The Provenance, formerly the Red Lion, awaits conversion to another use after 200 years as a pub

Another coffee shop?

The Coffee in the Wood coffee shop has been open at the south end of the High Street for just over a year.

Run by Kevin Godding, his wife Frankie and their daughter Sophie, it is covering its costs and thriving.

The family are now looking for ways to step things up and make more of a profit from serving 200 customers a day.

Opening up was not simple. It took a lot of market and business research, planning and investment.

Asking people what they actually want is the first step to any High Street revival, say the Goddings

For instance, it took 17 months to get planning permission to use what had been a former grocery.

But drawing on his first year's experience, Kevin passionately believes his High Street can be regenerated.

He says the first step is to do some proper research, with the help of the council and the Chamber of Commerce, to find out what local customers actually want.

"I think that people want to use their High Street, and we need to understand what that means, and not necessarily just for shopping," he says.

Still empty

Asking people what they want is not the banal idea it might sound, according to Matthew Hopkinson from the Local Data Company (LDC).

Even cafes have not been immune to the downturn in fortunes of the High Street

The LDC has spent the past 10 years analysing where UK businesses operate from, and where they should, or should not, be located.

The LDC's regular reports on shop vacancies show that the national vacancy rate is still stubbornly high at 13.3%.

So how would Mr Hopkinson approach revitalising a downtrodden High Street?

"Every High Street is very different," he points out.

"You have to understand who are the residents, visitors and workers in that High Street. That is where councils have been woeful in understanding what is going on.

"When you establish who those people are, what they do, what money they have and what they want to do, that is how the High Street should be structured," he adds.

Local convenience?

The aftermath of the great financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 led to a slaughter among the UK's retailers.

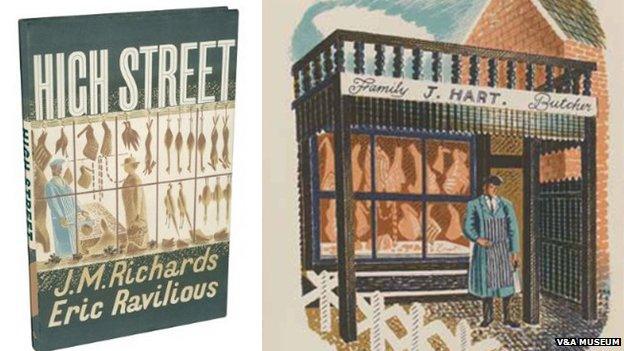

Nostalgia for the High Street dates back to before WW2, as seen in the book High Street, illustrated by Eric Ravilious

Many well-known names including Woolworths, Comet, HMV, Blockbuster, Jessops, Focus DIY, Habitat and JJB Sports all went down the pan.

In response, the government asked the TV retailing presenter Mary Portas to report on how depressed High Streets and shopping centres could be revived.

As a result, 12 towns were targeted for an injection of government cash to see if that would help them.

And since last year the government has been seeking the advice of a policy advisory group called the Future High Streets Forum.

Prof Neil Wrigley of Southampton University is the only academic on it. He says its members are optimistic that High Streets can adapt and not just die.

"The high point of out-of-town shopping is in the past," he says.

"People want a more local definition of convenience - there is very strong support for convenience outlets in town centres, where big food retailers have returned.

"On-the-go shopping, and top-up shopping, has increased significantly; the number of shopping trips people make has increased and the amount of travel people have done has also fallen significantly," he adds.

The Future High Streets Forum hasn't yet decided on what will work best to improve the different types of town centres and High Streets.

But things like slashing business rates on High Street premises, easing planning restrictions, and rolling back aggressive anti-parking measures, may all be part of the mix.

'It is too late'

A recent report from Experian looked at 2,000 shopping locations and how they have changed over the past 10 years.

Richard Hyman predicts even more shop and store closures in the next few years

The number of convenience stores, tattoo parlours, takeaway and fish and chip shops, betting shops and health clubs has soared.

And the number of video rental outlets, film developers, women's wear shops and travel agents has slumped.

But those recent trends are only a small part of the wider picture.

The veteran retail analyst Richard Hyman believes that the whole of the UK retailing industry is in the throes of even more profound change than in the 1950s, when self-service shopping and supermarkets gained ground.

"Retailing has become a less profitable industry across the board," he points out.

"The bottom line is that there is far too much capacity - there are far too many companies selling far too many products."

Partly thanks to stagnant living standards, the failure of internet shopping to cut overall retailing costs, and competition from the likes of Aldi and Lidl, he forecasts a further big cull of retailers in the next few years.

And that means that unless something really dramatic happens - like abolishing the motor car - a general return of decrepit High Streets to their former role as all-purpose shopping destinations will be impossible.

"It is too late, it can't be done," he says.

- Published9 October 2014

- Published5 October 2014

- Published4 April 2014

- Published30 March 2012