The secrets behind Hungary's escape games craze

- Published

Zoltan Kovacs takes you behind the scenes at a Trap escape game

Being locked in a dingy cellar for an hour with fiendishly difficult problems to solve isn't everyone's idea of fun. But in the Hungarian capital Budapest, "escape room games" are luring in tourists and locals alike. So what's the appeal?

If I'm honest I can't make head nor tail of the drawing in front of me. It looks like a plumbing diagram.

And while it's clear that the sequence of noises - a church bell ringing, a frog croaking, a cat mewling - are code for something, I am none the wiser.

I'm in a dimly lit cellar, furnished with creaking chairs, broken toys, and old computer monitors. The low-arched brick ceilings have been whitewashed, but there are few other concessions to civilisation.

Peeling paint and low lighting add to the atmosphere

But sometimes it's hard to tell what is a clue and what is just part of the sinister decor

With time pressure mounting it's vital that my team and I piece together some kind of logic among the junk, if we want to make an escape. That's the challenge. Identify each puzzle in the room, unravel its mystery in turn and you may get out before your allotted hour is up.

But still ringing in my ears are the words of owner Attila Gyurkovics before he locked us in: "Getting out is not guaranteed."

Hidden objects

Parapark was Budapest's first escape room game, based on the timeless truth that everyone relishes a challenge.

For just over 8,000 forints (£20) a team of up to five people has 60 minutes of complete distraction from the real world above. And despite Attila's ominous tone there is no real price to pay, except frustration, if he has to unlock the door for you in the end.

After wrestling with puzzle pieces, a broken doll and intermittent blackouts we're eventually free and Attila, a former social worker, tells me how the idea for Parapark occurred to him just over three years ago.

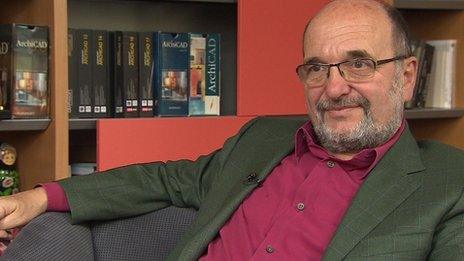

Attila Gyurkovics came up with the escape game three years ago

"I was playing computer games - hidden object games - with my girlfriend," he says.

He noticed how absorbing they were, how despite their artifice, he was so swept along he stopped noticing the time passing.

"After a while I thought, 'That's what we have to do in real life.'"

Faded grandeur

Since Parapark opened its doors in 2011, Hungarians have taken the concept and run with it.

In Budapest it is estimated there are now about 60 different escape games.

The themes are pleasingly varied, including joining Alice down the rabbit hole, racing to defuse a suitcase bomb and being trapped in a psychiatric ward.

There's one obvious reason why Budapest is the crucible for this burst of creativity.

Many Budapest properties are in need of renovation

The streets are lined with majestic Habsburg era townhouses. But their grandeur is fading. Chunks of plaster lie in the gutters and broken windows indicate empty properties, even in the city centre.

The financial crisis knocked the wind out of Hungary's property market and you can rent an apartment for just a few hundred dollars a month. A cellar costs even less.

Tomb raiders

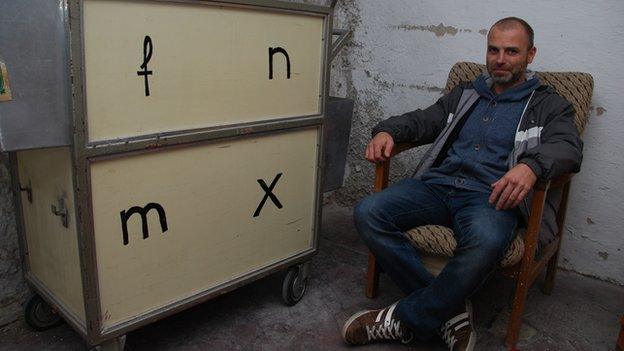

"The truth is conditions are ideal here for this game, as if these cellars were made for this," admits Zoltan Kovacs, who runs Trap, another escape game company in Budapest.

"The premises are so cheap. It's easy to get a permit. Everything is suitable for making easy money. It's tempting to try it."

In some ways it's too tempting. The main worry for established businesses like Zoltan's is the explosion of new games, some of which have been thrown together quickly and cheaply to cash in on the craze.

Trap's games are more elaborate than most. The props and puzzles are purpose built from glass, wood and metal, while a sophisticated network of electronic triggers opens up secret passages and new challenges. It takes his team six months and around £8,000 to develop a new game.

Zoltan Kovacs is taking the idea of exit games into businesses and schools

As we're talking a team of foreign students arrives.

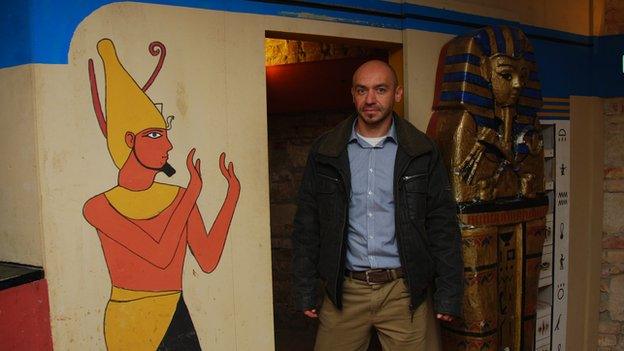

One room here is furnished like a medieval castle complete with gallows, an axe and a treasure chest.

But the group is eager to pit their wits in the other game: the ancient Egyptian tomb.

Puzzle masters

So just how smart do you have to be to solve the puzzles? Zoltan claims no specialist knowledge is required beyond secondary school level.

He left school as soon as he could and says if he can solve a puzzle it's not too difficult.

But he did pass his leaving exam, and it's worth noting that Hungary's traditional education system expects students to be proficient in geography, physics and arithmetic.

Moreover Hungary is famous for producing both world-class chess players, and a high number of Nobel Prize winners in maths and science. Houdini was born in Hungary.

Is it possible that Hungarians have a special affinity for these kinds of brainteasers?

"Under communism we were forced to be creative and resourceful," says Zoltan.

"There is a theory that because we were closed off from the rest of the world we turned towards games. This is why Erno Rubik invented his cube. We had nothing else left."

No specialist knowledge required, just a logical mind

But that doesn't prevent moments of individual frustration

'Like reality'

The rest of the world is taking to Hungary's games now too.

Copies have begun to spring up in other European cities, almost all offshoots or franchises of Hungarian ones.

Trap is expanding to offer corporate team-building, a mobile game, and versions to use in schools. Zoltan's eyes light up as he describes his idea for a game based on 19th Century inventors such as James Watt and Thomas Edison.

Finally the team of students appears through the exit. They have done rather well, locating secret panels, deciphering hieroglyphs and confronting mummified heads.

And despite the effort, they've enjoyed the experience.

"It's really realistic. That's what makes it special," says Manuel from Germany.

"You're really trapped in a room... sometimes when you're into it, it doesn't feel like a game. It feels like reality somehow."

"You have to try it - because it's Budapest," says his French teammate Francois. He shrugs. "Just try it."

- Published4 June 2024

- Published12 May 2014