The year in business: A review of 2014

- Published

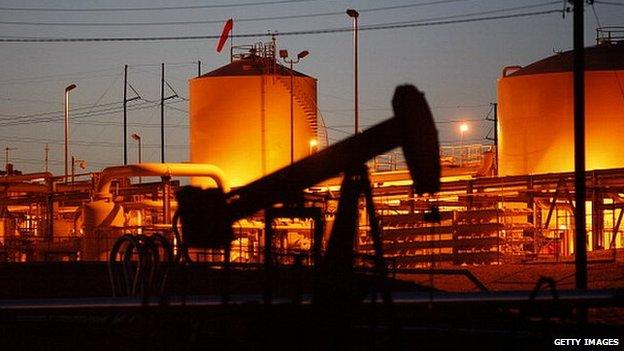

The boom in fracking in the US has contributed to markets being awash with crude oil

Throughout 2014, the shine seemed to come off a multitude of big ideas. Many of these global visions had seemed - until recently - unstoppable.

One idea was that post-cold war Russia could be economically integrated into the west. The sanctions against Russia after events in Crimea and Ukraine buried that notion.

Meanwhile, global efforts to tackle climate change have clearly lost momentum, Opec's power to stabilise oil prices seems to have evaporated, while Europe's single currency is still being blamed for the continent's continuing economic woes.

In all cases, it seems the big vision just hasn't delivered, and voters and politicians are looking more at what's in their own national interests.

Italy may contain some of the world's most beautiful buildings, but its economic statistics in 2014 were decidedly ugly. The economy had its third year in a row of contraction. Unemployment among young people is now a shocking 43%.

Italy's Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, is trying to stimulate employment by allowing firms to hire and fire more easily, but this prompted angry protests.

One protestor at a big demonstration in November told the BBC: "The way they want to change the labour market is outrageous. It would mean that workers become slaves.

"They want the unions to vanish. Mr Renzi speaks to the business leaders but he doesn't talk to the unions."

Protesters say the burden of employment law reforms are being placed unfairly on workers

But others feel regulations do need to change. Professor Giovanni Orsina from Rome's LUISS University says it is wrong that people who do their job badly in Italy cannot be fired. He told us: "I am a university professor, I am unfireable - this is obscene, I believe."

End of the eurozone?

As the year drew to a close, I spoke to two influential economists. Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator, at the Financial Times, and Peter Morici, professor of international business of Maryland University in the US. Both focussed on the euro as a fundamental cause of Italy's and Europe's continuing economic problems.

Peter Morici was blunt: "Now it's time to junk the euro".

He argues that the euro has led to chronic imbalances among the countries using it, so that the Germans and the Dutch have an undervalued currency.

On the other hand, the Italians and the Greeks have an overvalued currency, and can no longer use government spending to replace demand in the economy.

Martin Wolf said the Italian labour market rules were not the reason that Italian youth unemployment is now so high. He blames "the massive cyclical downturn since 2007".

"Southern European countries have very inflexible labour markets which tend to generate structurally high unemployment, that's undoubtedly a problem," he argues. "It should be fixed, but it won't suddenly transform growth, that's nonsense."

In January 2015 Lithuania becomes the latest country to adopt the euro, but is the eurozone fatally flawed?

Mr Wolf agreed that the current arrangements in the eurozone won't be able to generate enough demand. He thinks moving towards a euro-federal treasury is vital and, given that this is unlikely, there is a greater than 50% chance of the eurozone breaking up over the next few years.

Any break up would be a traumatic economic and political event, he says.

"The resistance to this will be colossal. It will go on for years. It will be unquestionably in the short run, an economic disaster, and in the long run probably a political disaster."

He thinks the European Central Bank is slowly moving to presenting the Germans with the option of either accepting big changes or leaving the euro.

"The neatest way of resolving the dilemmas is for Germany to leave. That could cause a very nice adjustment."

Prof Morici says he doesn't believe Germans will accept the radical changes needed: "Essentially, you're asking Germans to borrow for the whole of Europe.

"Politically, I doubt that Angela Merkel can pull that off. That is why I don't believe that the euro is viable."

Despite the best effort of European governments, growth in the EU remains weak

Squeezed middle

Growth in the past year picked up to between 2-3% in some developed economies like Britain and the US. But even here, celebration was very muted.

Most of the increased income appears to have gone to richer citizens, leaving those in the middle still worse off. For example, in the US, middle income workers still earn less in real terms than they did in 1999.

Prof Morici says changing technology as well as China's undervalued currency is causing middle technology jobs to leave the US and Europe.

"I think we should recognise that the period between 1950 and 1980 was an unusual period in western history, in which there was a massive increase in what you could earn for an ordinary education doing rather ordinary things that didn't really require a lot of skill."

It is not sensible for the US and many European countries to send 50% of their children to college, expecting them all to somehow be legislators or managers, he says.

"That's a hard reality that Europeans and Americans haven't been able to face.

"They have a lot of unemployment among their own children, and then they import people from the third world to do the jobs that they won't do."

Technological changes are causing shifts in global employment, seeing some jobs leaving the US and Europe

Bad banks

The big global banks continued to be punished for unethical behaviour

In November, UK and US regulators fined five banks a total of $3bn (£1.9bn) for manipulating foreign exchange markets. Citibank, HSBC, JP Morgan, RBS and UBS had all been rigging prices.

Prof Morici believes these banks should be split up, so that their retail banking divisions that lend to ordinary people and businesses are separated from their divisions that trade in financial markets.

Under the current set up banks are losing interest in lending to the real economy if they can use their money instead to make trading bets, which are, in the short term, much more profitable, he says.

Mr Wolf was on the UK commission which recommended that the UK government forced banks to ring-fence their trading divisions from their retail banks. He agreed with Prof Morici that the US rules using regulations rather than structural changes were moves in the wrong direction.

"This complex regulatory structure won't work," he says, favouring either the ring-fence or the Morici solution: "It doesn't make much difference to me if it's ring-fence or complete breakup."

Governments failed to agree to take more radical measures on combating climate change this year

Oil price falls

The fall in the price of oil over recent months has been dramatic.

Crude oil dipped to $40 a barrel after the 2008 financial crisis, but then stabilised around $100 for five years, before falling from this summer onwards to below $60 a barrel now.

The oil producer's group Opec has seemed unwilling or unable to stop the slide, as demand from China and Europe failed to live up to expectations.

The failure of Opec to maintain a grip on oil prices is unlikely to convince many people to shift to cleaner energy sources or go by public transport.

As a result the world is unlikely to live up to its earlier promises to keep down the growth of emissions that most scientists say are leading to climate change. A conference in Lima in December failed to come up with dramatic global commitments.

The inaction on the climate appears to be another sign that the world's most powerful governments have trouble uniting behind a common purpose.

The post -WW2 era of western economic dominance has ended, argue many

Changing world order

Prof Morici argues that the period after World War Two was unusual: "A clubby group of nations controlled the western economy.

"Now the south is much bigger, they don't like the rules we have created, they don't like what we aspire to in terms of multi-party democracies or market capitalism.

"The notion of having a set of rules that brings a simpatico set of economic powers into some sort of convergence and cooperation is probably ruptured and we are going to be living in a more chaotic world."

Martin Wolf agrees that many big global ideas are no longer likely to be achieved: "I think that we've passed the high stage of the legitimacy of the globalising project.

"Vast economic and other forces are pushing us to globalise and integrate and we are getting a very powerful and ongoing political backlash against those sort of projects.

"I would also stress that within countries, there's a real stress between the successful globalising elements of our communities and the people who are angry, frustrated and therefore inevitably are moving towards xenophobic and populist politics."

You can listen to Martin Webber's review of the world in business in 2014 at 17:32 GMT and 22:32 GMT on 25 December in World Business Report on BBC World Service, or you can download the programme podcast here.

- Published27 December 2013

- Published24 December 2012

- Published29 December 2011

- Published27 December 2010