Regret apps: The undo button for instant messaging

- Published

The company's motto is "What happens on Strings, stays on Strings"

How many times have you messaged someone on the spur of the moment only to wish you could take it back seconds later?

Well, as they say… there's an app for that.

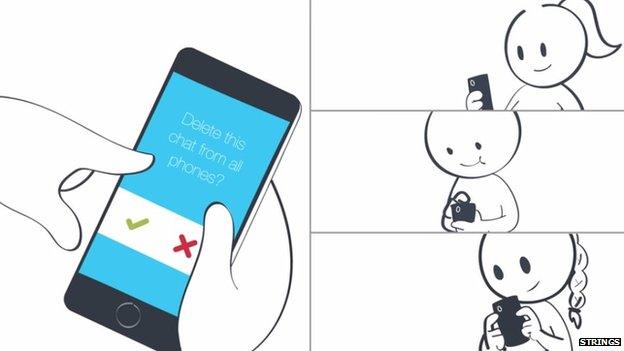

US-based company Strings has launched an instant messaging app that lets you "share what you want with who you want and take it back, if you want."

It's a catchy motto, but how does it work?

Strings chief executive Edward Balassanian says the free app allows you to delete sent messages, images and videos from your phone as well as the phone of the person that you sent them to.

The app also prevents the recipient from downloading, sharing or even getting a screenshot of your content without your permission.

The catch is that the recipient needs to be a user of the messaging app as well.

"For example, if I create a string and I add you and two other people to it, everybody in the string can see the conversation, but nobody in the string can add other people to the conversation without my permission and can't copy content out of the string," Mr Balassanian says.

Part of the company's mantra is "what happens on Strings, stays on Strings", so you always have control over the content, he adds.

Regrets, I've had a few

One person who might have found such an app useful is Nadia Rashad-Choudhary, 32, a personal assistant based in London.

She admits to texting, messaging and posting content in fits of anger...and regretting it.

"Oh no...why did I say that?" - the perils of instant messaging

"When I was angry, I would put up this rant. I would also post quote images that would relate to the situation," she says of past incidents.

"About 10 to 15 minutes later I would think: I shouldn't have done that."

Ms Rashad-Choudhary recalls posting photos on Facebook of her having fun on the same day she had already called in sick to work.

She'd forgotten that her supervisor was one of her friends on the social media site.

"I got a warning," she says. "Work-wise that was my first lesson never to post anything on Facebook, or never have work-related people as friends."

Staying power?

While the Strings app is not the first of its kind in the market, its popularity has skyrocketed since the beta version was launched on 31 December.

Mr Balassanian says Strings had 1,000 users upon its launch and has been downloaded more than 40,000 times since.

Other apps featuring messages that self-destruct after a set time include Invisible Text and Ansa.

And On Second Thought allows users to recall texts before the recipient receives them and also set a curfew for messages to be "embargoed" until the next morning.

The complete version of Strings is set to be released in a couple of weeks, but whether it has the staying power to succeed in a competitive market remains to be seen, according to analysts.

Deleted...really?

Shiv Putcha, associate director of consumer mobility at IDC Asia-Pacific, says there are several issues with this type of app, including whether the content you delete is truly gone.

"Something like a Snapchat proved recently that it [the content] doesn't actually disappear - there is a trail somewhere out there," he says. "It might disappear from each other phones, but there's no guarantee it's gone if the messages were stored on a cloud server somewhere."

Strings, however, claims that once a user deletes content from a conversation, it is removed from their phone, all devices it was shared with, and the company's servers.

.jpg)

Hackers stole photos from popular messaging app Snapchat

Snapchat, a popular three-year-old app that allows users to share photos and videos that automatically disappear after a few seconds, admitted last year that rogue third-party apps had been storing its users' pictures.

The admission came in October after hackers forums claimed that a file containing at least 100,000 stolen Snapchat photos had been created.

Despite the controversy, Snapchat still remains popular among young people with over 100 million users.

Ajay Sunder, of Frost & Sullivan's telecoms division, says as long as the user's content is not on a public domain and they feel secure that it will not be used for documentation purposes, people will continue to use such messaging apps.

"I do see a usage for these kinds of apps," he says. "[Mainly for] a younger generation who are much more brash and open to telling their ideas and later on realising it might not be sensible to say everything out there or message everything you think."

Despite the app claiming that you can delete messages from its servers, analysts say data may never truly be gone

Leaving 'bread crumbs'

The emergence of these types of "regret" apps is evidence that people are becoming more aware that they are "leaving bread crumbs all over the place", says IDC's Mr Putcha.

"There are more cases of these [posts] coming back to haunt people. You apply for a job and they check your Facebook profile and see silly photos of you at a party and check some tweets you've put out," he says.

"There are several things that companies regularly check, and how do you go back now and delete all of this?"

The right to be forgotten is no longer possible in the online culture of "over-sharing", especially in the Western world, says Mr Putcha.

"Just try deleting your Facebook account, that itself is very hard to do," he says.

Removing online content permanently is not as simple as deleting posts, say analysts

While Strings claims it lets users "pull all the strings" on their content, some analysts believe there could be regulatory difficulties concerning the private content that people want to take back.

And in the wake of the Paris terror attacks, governments are increasingly keen to gain access to messaging app content, says Mr Putcha.

Prime Minister David Cameron recently called for a change to online data laws that would allow authorities to read private messages, even if they are encrypted.

"There's no guarantee of complete privacy in a messaging application," Mr Putcha adds.

- Published13 January 2015

- Published28 March 2014

- Published18 December 2014

.jpg)