ECB expected to inject up to €1 trillion into eurozone

- Published

The European Central Bank (ECB) has confirmed it will shortly announce "further measures" to stimulate the ailing eurozone economy.

Reports say the ECB will inject up to €1 trillion by buying government bonds worth up to €50bn (£38bn) per month until the end of 2016.

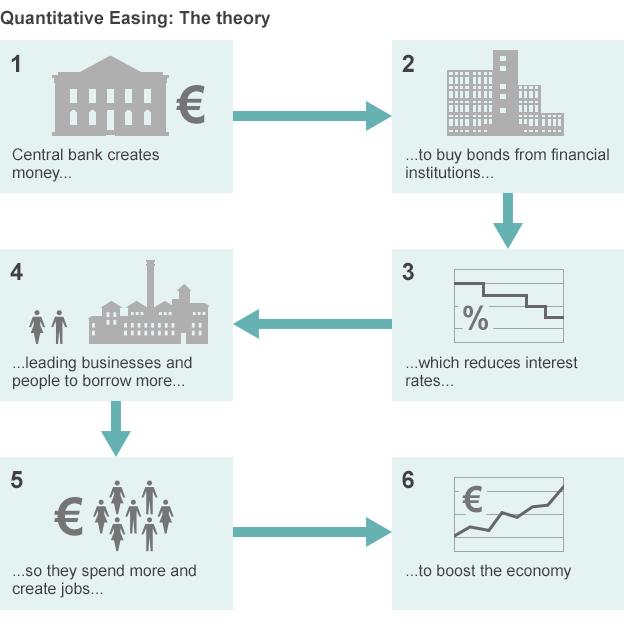

Creating new money to buy government debt, or quantitative easing (QE), should reduce the cost of borrowing.

The ECB also said eurozone interest rates were being held at 0.05%.

The eurozone is flagging and the ECB is seeking ways to stimulate spending.

Lowering the cost of borrowing should encourage banks to lend and eurozone businesses and consumers to spend more.

Big bazooka

It is a strategy that appears to have worked in the US, which undertook a huge programme of QE between 2008 and 2014.

The UK and Japan have also had sizeable bond-buying programmes.

What is a government bond?

Governments borrow money by selling bonds to investors. A bond is an IOU. In return for the investor's cash, the government promises to pay a fixed rate of interest over a specific period - say 4% every year for 10 years. At the end of the period, the investor is repaid the cash they originally paid, cancelling that particular bit of government debt.

Government bonds have traditionally been seen as ultra-safe long-term investments and are held by pension funds, insurance companies and banks, as well as private investors. They are a vital way for countries to raise funds.

Up until now, the ECB has resisted, although the bank's president, Mario Draghi, reassured markets in July 2012 by saying he would be prepared to do whatever it took to maintain financial stability in the eurozone, nicknamed his "big bazooka" speech.

Since then, the case for quantitative easing has been growing.

Earlier this month, figures showed the eurozone was suffering deflation, creating the danger that growth would stall as businesses and consumers shut their wallets, as they waited for prices to fall.

Whose debt?

The ECB's bond-buying programme is likely to begin in March, although the final decision over whether to start the measures will be taken at a meeting of the bank's 25-member policy-making board on Thursday.

There remains a possibility that the German members of the board will object to the plan. They would prefer any government bonds purchased to be held by national governments, rather than centrally by the ECB. That would reduce the risk of a default by struggling peripheral countries, such as Greece and Italy, being shouldered by the richer members of the eurozone.

On Wednesday, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) urged Mr Draghi to pursue uncapped quantitative easing.

Angel Gurria, secretary-general of the OECD, told the World Economic Forum in Davos on Wednesday: "Let Mario go as far as he can. I don't think he should cap it. Don't say 500bn [euros]. Just say, 'As far as we can, as far as we need it.'"

J.P. Morgan Chief Market Strategist Stephanie Flanders explains why quantitative easing has to be believed to be seen

However, some economists and analysts have expressed reservations about the idea.

Joerg Kraemer of Commerzbank told BBC World Service's World Business Report programme that there was "no real threat" to the eurozone economy from deflation.

He added: "A mild decline in prices is no problem for real GDP growth, and especially in the eurozone. The only reason why we have a negative inflation rate is the decline in oil price, but the decline in oil price is good for the economy."

UK economist Roger Bootle of Capital Economics told the programme: "I am not the greatest fan of quantitative easing - I don't think it's going to cure the European malaise. The point is, there is not much else in the locker."

- Published22 January 2015

- Published20 January 2015

- Published28 November 2014

- Published20 January 2015

- Published25 November 2014

- Published14 November 2014