F1 tech still shaping tomorrow's transport

- Published

Great Britain's Mike Hawthorn (foreground) takes part in the 1958 Grand Prix at Silverstone

Motorsport has a long history of feeding its innovations into road cars. And that technological transfer is set to continue into the future.

In fact, it may well get faster.

Integral features of motorsport - speed, safety, data communications, fuel efficiency - are more relevant to road cars than ever before.

Formula 1, and endurance races like Le Mans, will continue to pass on their DNA to the cars we drive today and tomorrow.

The all-electric Formula E racing series will undoubtedly do the same.

Paddle shift gear-changing, braking systems, hybrid engines, lightweight carbon fibre materials and energy recovery systems, have all helped "improve the breed", as the saying goes.

"The first thing your garage does when you go for a service is plug its diagnostic computer into the car's electronic control unit [ECU]," says Matt Harris, head of IT at the Mercedes AMG Petronas F1 team.

McLaren's new 650S supercar borrows a lot of technology from its F1 sisters

ECUs were a part of F1 long before they went mainstream.

Showing what's possible

But these days, the technical crossover is "a more subtle process than bolting bits from one car onto another", says Paddy Lowe, Mercedes F1 technical director.

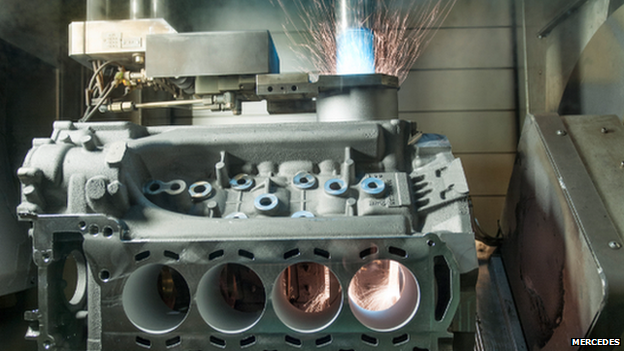

"There are examples of direct transfer - for instance the Nanoslide technology used to coat cylinder bore surfaces [to reduce friction].

"And then there is indirect transfer, where F1 serves as research laboratory for developing new solutions and showing the world what is possible."

Mercedes' Nanoslide tech gives engine surfaces an ultra-fine coating to reduce friction

F1 tech shaping tomorrow's transport

Mercedes dominated last year's F1 World Championship due to a new smaller and more powerful engine that enabled a different layout inside the car, which itself enabled better cornering and a more efficient use of the front tyres.

Such incremental advances will eventually be embedded into road cars.

However, the technology is no longer a one-way street. With racing engineers working alongside road car engineers, the shared expertise is "a loop of mutually beneficial exchange", says Mr Lowe.

And in the modern technological age, that cross fertilisation of ideas also unites once-disparate industries.

For example, Mercedes shares information on aerodynamics and computational fluid dynamics (flows of liquids and gases over materials) with US space agency Nasa and defence group BAE Systems.

McLaren and Specialized have created high-performance road bikes, such as the S-Works McLaren Tarmac

The Lotus team has a similarly symbiotic relationship with aircraft manufacturer Boeing.

And McLaren's expertise in data analysis and simulation has meant working with oil and gas firms, accountancy group KPMG, and cycle racing teams.

Data driven sport

These core skills will become more valuable. F1 expertise in real-time data collection, transmission and analysis could help underpin the smart traffic management systems and driverless vehicle networks of the future.

Tomorrow's transport will be as much about data and connectivity as about vehicle design and new power trains.

Caroline Hargrove, director of McLaren Applied Technologies, external, told the BBC: "We have a lot of experience in scenario planning and predictive analytics.

"During a race we run a load of scenarios in the background so that as something happens we can make split-second decisions. We try to find nuggets of information in the data and then make sense of it."

Tata Communications, part of the Indian conglomerate that owns Jaguar Land Rover, handles data feeds for F1 Management and also the Mercedes F1 team.

Tata collects about 400GB of data during a race weekend, transmitting it back from Melbourne, say, to Mercedes' F1 UK headquarters in 300 milliseconds.

Mercedes dominated the 2014 F1 World Championship, the first to feature hybrid engines

Here, engineers dissect information recorded by up to 200 sensors embedded in an F1 race car.

The more sensors you have, however, the heavier the car becomes - and weight is the enemy of speed and fuel efficiency.

So, although the connected, driverless road car may be the future, companies like Tata must continue to eke out fractional improvements in the technology to ensure that it works with optimum efficiency.

But progress in "connected motoring" could be hampered by poor mobile network coverage, believes Mercedes' Matt Harris.

"It's still the weak link in the chain," he says.

Mehul Kapadia, managing director of Tata's F1 business, agrees, saying: "When an ambulance is en route to the hospital and is sending data about the patient to the doctors and nurses, you're going to need a reliable data link."

'Real world'

Big technical leaps - such as Jaguar's groundbreaking work on disc brakes for its road racing in the 1950s - are rarer these days.

F1's strict rules, designed to level the playing field for all competitors, give less scope for pushing engineering boundaries.

But that has made the sport even more attractive to carmakers.

Williams Advanced Engineering helped power Jaguar's electric supercar

"Why would Honda come back into F1 if the sport had no influence on the real world?" asks Mr Kapadia.

His answer: "F1 cars are now more like road cars than ever, particularly when it comes to fuel efficiency."

What's more, the racing teams themselves are more adept at commercialising their technology.

Tomorrow's Transport is a series exploring innovation in all forms of future mobility.

Williams Martini Racing is far more than just an F1 outfit these days. Its Williams Advanced Engineering (WAE), external division has just opened a new multi-million-pound factory at the group's headquarters near Oxford.

Such is the demand for Williams' expertise that WAE's managing director, Craig Wilson, expects the number of staff to double from the current 150 within a couple of years.

One of WAE's big successes is its Kinetic Energy Recovery System (Kers) flywheel, which captures energy generated during braking, stores it, then releases it to give a power kick.

Williams Hybrid Power energy storage technology will be applied to Alstom trams

Kers was subsequently banned in F1, but Williams adapted its electric flywheel for Porsche and Audi, and then for use on public buses.

The concept was sold to engineering company GKN last year. Mr Wilson says: "The technology had matured to a stage where the idea was proven and it was right for it to go into high-volume production."

Peddle power

Williams also supplies the battery power units for all race cars in the new Formula E (FE) Championship.

This series is more than just motorsport. It's mission is to prove that electric vehicles not only work, but are exciting.

Under pressure to meet emissions targets, governments and carmakers have put a lot of political and financial clout behind FE.

The genesis of FE batteries was the work Williams did in F1, and then on an electric supercar for Jaguar.

The battery technology in Formula E racing cars will find its way into road cars

Williams supplies the batteries for all 42 racing cars competing in the all-electric Formula E Championship

Already, FE battery derivatives are being used on road car demonstrators.

"We are sure that the FE technology will find its way into road car programmes," Mr Wilson says.

And just to prove that F1 tech spreads it net wide, WAE is working with Brompton, maker of the famous fold-up bicycles, on a battery-assisted version.

"Brompton is a particular technological challenge," says Mr Wilson. "They need something light, powerful, but small enough so the bicycle can be folded. But we're pretty certain we can produce something leading-class.

"F1 is good at squeezing tech into small spaces."