Greece: What are the options for its future?

- Published

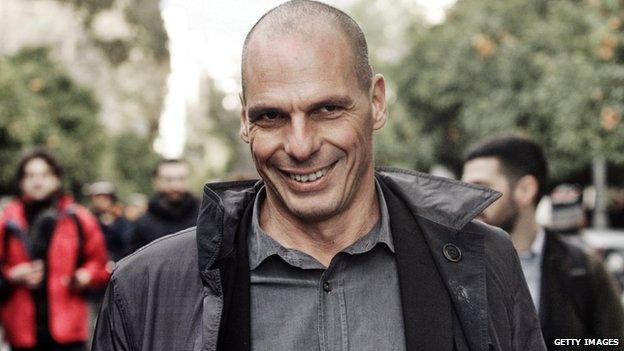

The face of the future: Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis wants to negotiate a new deal for Greece

On Wednesday the future of Greece was laid out in Brussels.

On one side of the negotiating table stood Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis determined to ease the burden of his country's debts.

On the other its main creditors - the International Monetary Fund, the European Union and the European Central Bank - determined there would be no change to the terms of its €240bn (£178bn) bailout.

Neither side have used the word compromise.

But IMF chief Christine Lagarde, has already admitted: "We have to listen to them, we are starting to work together and it is a process that is starting and is going to last a certain time,"

The IMF's Christine Lagarde and Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis. "We are starting to work together".

What is decided in the coming days and weeks will determine Greece's economic future.

It may even decide the future of Europe.

These are the possible options.

Scenario 1: Greece gets what it wants

This scenario is highly unlikely because the eurozone, and Germany in particular, are so opposed to it.

It sees two bailout packages being approved.

The first is a bridge loan to keep Greece going for six months and help it repay €7bn (£5.2bn; $7.9bn) of maturing bonds.

The second would be a refinancing of debt to last it four years. Part of this might be through "GDP bonds" - bonds carrying an interest rate linked to economic growth.

There would also be a reduction in the primary surplus target - that is the surplus the government must generate(excluding interest payments on debt) - from 3% to 1.49% of GDP.

There would be a renegotiation of reforms, and increased spending to meet the "humanitarian crisis" - a higher minimum wage, better pensions and the rehiring of civil servants.

Such a deal would certainly ease the pain of austerity.

By increasing government spending, Greece stands less chance of reducing its debts, but perhaps more chance of kick-starting some growth.

GDP-linked bonds may be attractive to borrowers in a stagnant economy, but they mean lower returns, especially in the short term, for lenders.

Not only that: it also spreads fear that countries like Spain and Italy might follow Greece's example. That would increase their borrowing costs - the "contagion" economists dread - and encourage them to negotiate for similar deals.

Scenario 2: A fudge ("a negotiated settlement")

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble - tough stance

Any negotiated deal depends on the language it is couched in, so that it can be sold to the respective electorates.

For instance, Greece has insisted it will on no account have an "extension" of the bailout. Any compromise is unlikely to include the word "extension".

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble has taken an equally tough stance. He has said that Europe won't negotiate a bridge loan. So don't expect the word "bridge" to appear anywhere.

But Greece may well have to concede and accept in principle all its commitments to pay, one way or another, all its debts. That's a long way from the promises of "writing off" its debt that it made in the lead-up to the Greek elections.

In return, though, Europe may well allow flexibility in repayments.

This may include a moratorium allowing the country to skip interest payments during a given period (five to 10 years) or until economic growth gathers pace.

In fact, easier terms for debt repayments could free up cash, which, ironically, makes the country a better bet for new lenders.

On reforms the two sides are likely to get some agreement, with Syriza already demanding aggressive reforms on tax collecting and corruption.

But Germany will be tough on the question of austerity.

Failing to balance the books can be more damaging to the country's creditworthiness than letting it off its debts.

Austerity is meant to sort out government finances. Without a balanced budget, Greece will find it hard to find investors willing to lend.

Scenario 3: Greece finds cash elsewhere

Piraeus Port: A Grexit would bring hardship but also a surge in exports

If the money from the ECB stops, Greece can still get funds from its own national central bank in the form of emergency liquidity assistance (ELA).

But this will be of limited effect: the ECB can veto the ELA and has threatened to do so in the past, ahead of bailout agreements for Ireland and Cyprus.

But there could be other sources.

Greek Defence Minister Panos Kammenos told Greek television: "It could be the United States at best, it could be Russia, it could be China or other countries."

Kammenos is the leader of Independent Greeks, a nationalist party that is the junior coalition partner of the Syriza party.

Greece's Deputy Foreign Minister Nikos Chountis told Greek radio that Russia and China had offered Greece economic support - though Athens had not requested it.

This is not the first time the idea has been floated, and talks between China and Greece took place in 2011.

But so far China's financial commitment to Greece has largely been in privatisations, such as the selling off of the Greek port of Piraeus.

As for Russia, faced with heavy demands on its own reserves, it hardly seems an appropriate time to be handing out cash to impoverished Europeans.

On the other hand a few billion might buy it some political support from Syriza, which has already shown itself sympathetic towards ending Western sanctions on Russia.

As for the US, it seems unlikely that Mr Obama will go over the Europeans' heads to lend to Greece.

Scenario 4: Greece defaults

Pesetas anyone? A Grexit could tempt other countries to start reprinting their old currencies

If Greece defaults on its debt and leaves the eurozone it makes investors increasingly nervous about the likelihood of other highly indebted nations, such as Italy, or those with weak economies, such as Spain, repaying their debts or even staying inside the euro.

A lot will depend on how Greece fares outside the euro. There are two schools of thought here.

One believes the country will enter the economic equivalent of a nuclear winter. There would be a chaotic race to create the new drachma - distributing the new currency and even finding printing presses could prove next to impossible.

Repayment of any euro foreign currency debt using the devalued drachma would become a massive burden which the government might just give up on altogether, making it impossible to borrow on the international markets.

Imports would dry up - some of them, such as medical supplies, oil, raw materials and a range of food and everyday items, would create huge hardships. Inflation would spike dramatically and raw material shortages would cripple industry, creating unemployment.

Savers and investors would withdraw euros, causing massive capital flight.

However, the alternative view is that after an initial collapse, a wave of investment would come back into the country, tourism would boom and exports surge, creating jobs and slowly restoring the currency to some kind of strength.

As for damage to the rest of the world, the effects would certainly be less than say three years ago. Banks are hardly ignorant of Greece's risks and are better prepared to take losses on their Greek debt.

But if life starts to look substantially better for a drachma-based Greek economy, other countries may also start considering printing lira, pesetas and escudos, and the future, and creditworthiness of a slew of eurozone economies would be thrown into doubt.

- Published11 February 2015

- Published10 February 2015

- Published8 February 2015