Are superfast trains speeding down the tracks?

- Published

Futuristic cityscapes always seem to feature elevated railways

At the time the UK was completing its first stretch of high-speed rail in 2007, China had barely left the station.

Nearly a decade on, Britain still has only that same 68-mile (109km) stretch of track, but China has built itself the longest high-speed network in the world.

At more than 12,000km (7,450 miles) in total, it is well over double the length of the European and Japanese networks combined.

So if you want to get a sense of what the future of rail travel might look like, China would seem to be the place to come.

Vacuum velocity

As it stands, train technology doesn't seem to have changed much for decades.

The UK may have just received its first Hitachi-made Super Express high-speed train capable of running at up to 140mph (225km/h), but this is hardly a quantum leap forward.

The train was unloaded from a ship, as Richard Westcott reports

The much-loved InterCity 125 - as its name suggests - could do 125mph back in the 1970s. And France's TGV and Spain's AVE travel at more than 190mph.

So when will we see truly superfast trains bulleting through the countryside, capable of speeds of several hundred miles per hour?

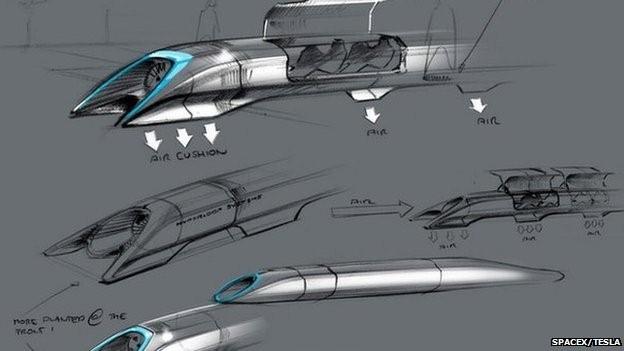

A lot of hopes are being pinned on "evacuated tube transport" (ETT) technology, inside China and elsewhere.

Friction is the enemy of speed, and air friction increases the faster we go. This means the current upper limit for conventional high-speed trains is about 250mph.

The world's fastest steam locomotive, Mallard, reached 126mph (203km/h) in 1938

So the theory is that by running trains through vacuum tubes, and raising them off the tracks using existing maglev [magnetic levitation] technology, drag could be reduced to near zero.

These ETT trains could potentially travel at over 1,000mph.

The Rand Corporation's Robert Salter proposed an underground version of such a transit system back in 1972. But it is only now that an overground version, based on the Hyperloop concept proposed by Tesla Motors and SpaceX founder Elon Musk, will be trialled in California next year.

China is already testing the technology - albeit on a small scale.

Dr Deng Zigang, from the Applied Superconductivity Laboratory at China's Southwest Jiaotong University, has built just such a system: a 6m radius vacuum train tunnel, and he has begun testing.

A five-mile (8km) Hyperloop test track is due to be built in California next year

Hot air?

But these are early days. Reports suggest Dr Deng's small train has so far only reached speeds of 15.5mph (25km/h), and there are many who doubt whether such technology will ever become a reality.

"Viable public transport needs a lot more than experiments," says Prof Sun Zhang, a railway expert from Shanghai's Tongji University.

"It needs to be achievable in construction, they have to be able to control the risk, and they have to have concern about the cost.

"So my personal view," he adds, "is that, at this stage at least, this is just a theory."

Jeremy Acklam, transport expert at the Institution of Engineering and Technology, agrees that a combination of maglev and vacuum technologies would be "very much more expensive" than traditional high-speed rail. "We need to ask ourselves how much extra speed is worth?" he says.

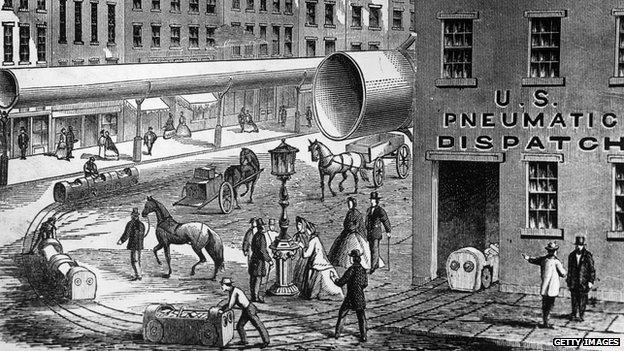

In 1868, Alfred Beach proposed a "pneumatic" elevated railway for New York

Maglev tech is expensive because the repelling magnets and copper coils use a lot of electricity, and the track infrastructure is far more complex than conventional steel rails.

"Achieving a vacuum across a long distance is a significant engineering challenge," says Mr Acklam.

Then there are the safety issues.

How would passengers be evacuated if the train broke down, and how would the emergency services gain access?

There's also the obvious point that many people might not like travelling in a tube with no windows to look through.

Tomorrow's Transport is a series exploring innovation in all forms of future mobility.

While TV screens and video projections could make the experience less claustrophobic, it would still take some getting used to.

Despite such drawbacks, Mr Acklam still believes that the hyperloop concept is one "whose time has come".

Maglev magic?

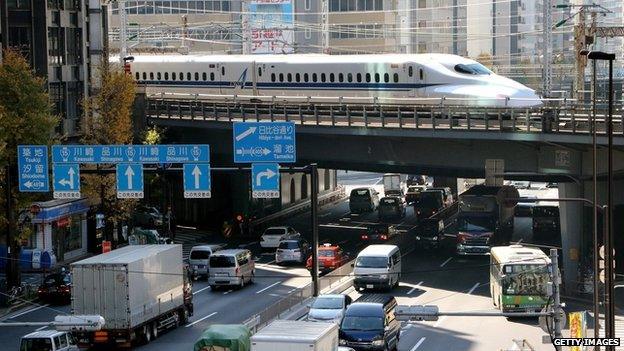

Meanwhile, Japan is powering ahead with maglev technology.

In October last year it approved plans to build what will be the world's fastest train line, capable of whisking passengers between Tokyo and Nagoya at more than 310mph (500km/h).

If the line is eventually built, for a cost of a little over $50bn (£34bn), it will be the world's first inter-city maglev line, shaving a whole hour off the current journey time of 1 hour 40 minutes.

Japan's experimental Tokyo-to-Nagoya maglev train could reach 500km/h (311mph)

Japan has long been famous for its Shinkansen high-speed bullet trains

China, of course, does have its own maglev line in Shanghai, carrying passengers from the international airport in Pudong into the city.

But it is often held up, not as a shining example of the benefits of high-speed rail, but of the pitfalls of pursuing big infrastructure projects for their own sake.

The line does indeed whoosh passengers into the city at breathtaking speed, but not to the city centre, meaning travellers then have to find other ways to complete their journeys.

And for many, now that the metro has been extended all the way to the airport, this offers a regular, reliable and cheap alternative.

Rail expansion

While we're waiting for these superfast trains to arrive, we'll have to make do with more conventional high-speed trains.

China's lead in the technology means it has become the partner of choice in more than a dozen countries. And it is in talks with many more.

No other country has seen such a rapid expansion of mass transportation.

The Beijing-Gaungzhou high-speed train line has cut the journey time from 22 hours to eight

And things look set to stay that way.

China is planning to double the size of its network again within the next five years or so and has recently confirmed plans to build a $242bn high-speed rail link to Moscow.

The benefit of all of this railway construction, at least in the short term, has been obvious in the form of a huge investment-driven boost for the economy.

And in such a vast country, reducing journey times has been good for business.

The train journey from Beijing to Guangzhou - now the world's longest unbroken high-speed rail journey at 2,298km - now takes eight hours rather than 20, and costs just over $100.

The main question for China is whether such a massive expansion is commercially sustainable.

"We're still seeing large growth in air and rail travel around the world," says Mr Acklam. "There doesn't seem to be a reduction in the need to travel in the digital era.

"Business always demands more speed."