The artisans in danger of disappearing

- Published

Industry leaders want a higher profile for a sector which they believe can play a key role in Europe

Pascal Bourdariat - just the 12th workshop director in high-end jeweller Chaumet's 235-year history - is watching as a worker gently polishes a tiny gem, so small it's almost invisible.

The knowledge of how to craft and design these intricate pieces takes as long as 10 years to amass, and has been handed on from one generation to another, with artisans today working in much the same way as their predecessors two centuries before.

It is in this workshop - which once made all Napoleon's official jewellery including his coronation crown - where all the special order and top collections are made.

In the past, Chaumet spent a whole year making just a single necklace

Making a product for this market is painstaking and time consuming work. A single piece, such as a necklace or tiara, typically takes six hundred to 1,000 hours to make, but can take as long as 2,000 hours depending on the quality of the stones used.

In the past, Mr Bourdariat says the company, now owned by LVMH the world's largest luxury goods group, spent a year making just one necklace.

The skills required to make unique masterpieces such as these, however, are at risk of disappearing in this modern age of mass production.

Mr Bourdariat estimates the number of craftspeople making such products in Paris has halved over the past two decades as a result of falling demand. He says this has led to a shortage of certain skills, without which it's impossible to make this kind of jewellery, such as moulding, setting stones and polishing.

Chaumet is trying to ensure its "savoir-faire" is handed on to the next generation

LVMH, which alongside Chaumet owns some 70 luxury brands including Louis Vuitton, Dior and Givenchy, last year set up a training scheme - called "L'Institut des Métiers d'Excellence" - aimed at addressing the skills gap, taking on 28 paid apprentices in different areas of its businesses.

The scheme aims to transmit its "savoir-faire" to the next generation "not only for LVMH's needs but also for the jobs, the art, the craft in itself," says Chantal Gaemperle, vice president of human resources and synergies at LVMH.

"We wanted to make sure that we will still have the craft that we need in the next 10 years. It's one of the ways to make sure that we fill the pipeline of talent, but also we don't lose the craft of very specific know-how in the different metier."

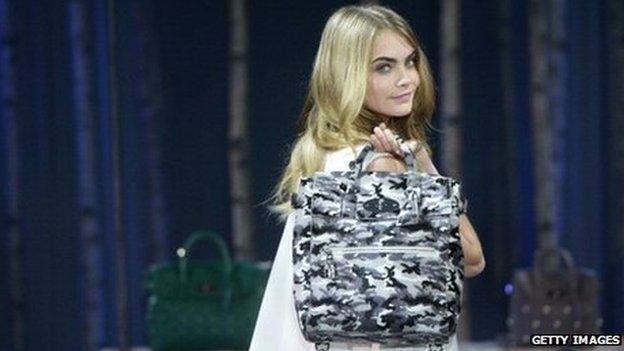

Mulberry, which Cara Delevingne has designed a range for, has taken on apprentices since 2006

Firms in the UK have done similar. British handbag maker Mulberry, for example, has been running an 18 month apprenticeship course, comprising a leather skills NVQ and technical certificate with a local college, since 2006. As a result, it says it now has a waiting list of young people wanting to join its production line team.

Firms are wise to act. The luxury sector, which includes high end cars, wine and clothing, is one of Europe's most important industries, worth some 17% of Europe's total merchandise exports in 2013, according to industry lobby group the European Cultural and Creative Industries Alliance (ECCIA), external.

And increasingly where something is made and how it is made are important factors for consumers when they make a purchasing decision.

ECCIA president Michael Ward says 80% of people look at a product's label first to see where it has been made.

"If we look at what's driving the luxury market; it's about craftmanship, originality and tradition. It's all about adding value. How many stitches in a Fendi bag, how long does it take to train a weaver, for example, are all hugely important in terms of the product proposition."

Shoppers in emerging markets prefer products made in the country of origin

It's also become an increasingly important issue for one of the biggest purchasers of high end goods - those in emerging markets. When my friend Simran, a Malaysian lawyer in her late thirties, visited London for work her first stop was the Mulberry shop.

Although she could buy Mulberry bags in Malaysia, they were more expensive there, and she wanted what she considered something quintessentially British, bought in the country it was made in. A souvenir from her travels but one that she was also certain her friends would appreciate and understand the value of.

Fflur Roberts, head of luxury goods at Euromonitor, says Simran's behaviour is typical.

"We're seeing a complete shift as emerging markets mature. They want to look at the label and see that it is made in the country of origin. Even if they can buy it in their home country, there are concerns over authenticity. Coming back from wherever you've been and showing off what you've bought goes with the theatre of the brand."

LVMH apprentice Maxim Fradin says he's proud to work with his hands

Yet despite the apparent glamour of the industry, recruiting people within the brand's home country to make the products can be difficult, even with the eurozone's stubbornly high youth unemployment rate, 22.9% at its most recent reading.

Elisabeth Ponsolle des Portes, the president and chief executive of French luxury goods association Comité Colbert, says many parents try to steer their children away from manual jobs, a trend it is trying to fight.

The body has fought hard to ensure official government recognition for the design houses preserving the skills involved, and it is now trying to get across the message that these skills can offer long term, rewarding careers.

"Our challenge is to show how far these trades are linked to innovation and creativity. They are not just hollow reproductions of old forms. They benefit from the knowledge of the past, but are completely in tune with the present."

Those who doubt it should speak to some of those currently learning the necessary skills.

LVMH apprentice Maxim Fradin says he is proud to work with his hands, likening his work to that of a musician. "It's the repetition of gestures, hours and hours of rehearsal work and then arriving at a convincing final excellence; the perfect object," he explains.