Can Africa fight cybercrime and preserve human rights?

- Published

As internet usage rises in Africa, so does cybercrime

Think cybercrime and Africa, and most people in the developed world think of the notorious 419 email scam.

This involves gangs extorting money from the likes of great aunt Mabel by promising her riches, if she'll just send some cash and/or her bank details to a nice man in Nigeria.

But cybercrime on the continent has moved far beyond this, with gangs embracing more sophisticated ways to use technology, such as malware and botnets, to get what they want.

Internet usage is rising rapidly in Africa, and with it, cybercrime.

This growth is making it easier than ever for criminals to operate. And it has created a new pool of potential victims lacking the knowledge and experience to be able to protect themselves effectively.

Victims

Security expert Kaspersky says more than 49 million cyber-attacks took place on the continent in the first quarter of last year, with most occurring in Algeria, ahead of Egypt, South Africa and Kenya.

But cybercrime is actually most pervasive in South Africa, with security firm Norton saying 70% of South Africans have fallen victim to cybercrime, compared with 50% globally.

McAfee, another cybersecurity firm, reported that cybercrime cost South African companies more than $500m (£340m) last year.

In South Africa 70% of people have been victims of cybercrime, says Norton

Baby steps

Africa has long lacked a legal framework for tackling cybercrime.

But in June 2014, the African Union (AU) approved a convention on cybersecurity and data protection that could see many countries enact personal protection laws for the first time.

For it to be implemented, however, 15 of the 54 AU member states will need to ratify the text.

As yet, not one country has done so, though there is optimism it will happen in the next three-to-five years.

"Cybersecurity is a growing concern for the nations of the African Union as more people come online," says Drew Mitnick, junior policy counsel at human rights organisation Access, which has called on member states to ratify the convention as soon as possible.

"It is critical for the countries to adopt cybersecurity policies that better protect users while respecting their privacy and other human rights."

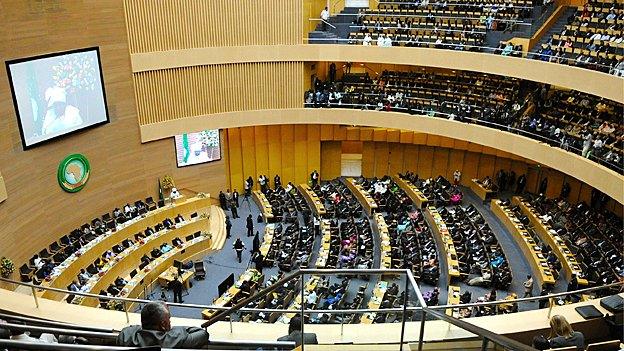

The African Union (AU) is made up of 54 member states - only Morocco doesn't belong

Access believes the AU should lead these efforts.

The group has tracked proposed cyber and data protection laws in Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritania, Morocco, Tanzania, Tunisia and Uganda.

In each case, the legislation would either fail to provide basic protection for user data, or allow the government to violate the rights of privacy, expression, and assembly, Access believes.

But Beza Belayneh, managing director of the African Cyber Risk Institute (ACRI), says there are positives.

"[The convention] is a jumpstart for many countries who do not have any legal ground or appreciation to combat cybercrime," he says.

"It is a good guide to develop... computer or cybersecurity laws in a localised manner. It is the best way just to start the job. It has to start somewhere.

"It is apparent that many, if not all, African countries lack the capabilities to defend their ever-growing cyber infrastructure."

Cybersecurity is finally receiving the attention it deserves, he added.

Ducks in a row

As a guide to helping African nations get their "cyber ducks in order", as Mr Belayneh puts it, the AU convention isn't too bad.

Mr Mitnick says the convention contains a data protection provision covering control of personal data, with a large part of it mirroring the data protection framework and language developed by the European Union.

He also commends the protection of human rights.

"The text requires governments to uphold the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, along with other basic rights such as "freedom of expression, the right to privacy, and the right to a fair hearing, among others," he says.

"The inclusion of privacy is most welcome, considering it is not explicitly found in the African Charter."

The AU proposals include giving judges unlimited power to issue search and seizure warrants on data or computers - causing understandable concern about human rights

'Negative effects'

However, there are real concerns about some of the provisions.

The Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law at Strathmore University, Kenya, is against implementation in its current form.

It believes the convention could limit freedom of expression and allow authorities to intercept private data too easily. Judges would be given unlimited power to issue search and seizure warrants on data or computers, for example.

All this could have "substantial negative effects on online economies and social cultures across Africa," it says.

A woman uses a tablet at an internet cafe in Dakar, Senegal

Mr Belayneh agrees that the document gives too much power to judges and law enforcement arms of governments, and says it fails to take into account the roles of education and consultation in combating cybercrime.

"It was written by lawyers," he says. "Cybersecurity and cybercrime need a multi-sectoral approach - cybersecurity educators, researchers, NGOs [non-governmental organisations], vendors, ethical hackers were supposed to be involved so they could present a multi-dimensional framework instead of legal paper."

Does criminalising "insulting language" allow governments to clamp down on dissent?

Some of the convention's phrases seem to be in direct conflict with protecting human rights.

For instance, while the convention limits the processing of personal data, it contains an exception for a task "carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority" - a loophole ripe for abuse, some experts believe.

Mr Mitnick says the convention could also pave the way for harsh criminal convictions.

"In one example, it limits the use of insulting language, which could describe a significant portion of the language on the internet and is likely to lead to subjective prosecutions," he says.

Though the experts believe the convention is satisfactory as a first step, the negatives are certainly clear for all to see.