Labour: Reshaping British capitalism?

- Published

- comments

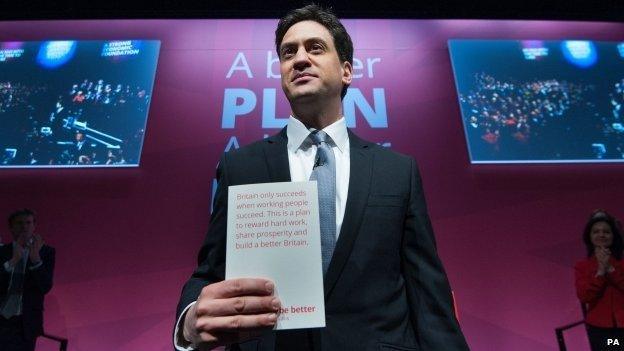

Labour today put their stance on public spending on the front page of their manifesto.

Despite some new rhetoric, the policy remains broadly unchanged - Labour will aim to balance the "current budget" (which excludes capital spending on investment) "as soon as possible", while the Conservatives are aiming for an overall budget balance.

There remains a large gap between the two big parties.

But there's more to economic policy than public spending. Look beneath the surface and Labour's manifesto sets out an ambitious economic programme that is very different to both the approach of Tony Blair and the position Labour seemed to be in, in the first half of this parliament.

In 2010 Labour's central economic "dividing line" was "investment vs cuts".

In economic terms, the focus was on the demand side of the economy.

Labour's central argument from the election until 2012 was that by cutting public spending "too far and too fast", the government was sucking too much demand and spending power out of the economy.

With the economy growing, Labour's critique has shifted to the supply side of the economy and honed in on the weakness in productivity growth.

Output per hour, worked in the UK, has now flat-lined since 2008, a unique seven-year period in post-war history.

Central idea

Much of Labour's economic policy flows from a central idea: that something went wrong in the British economy well before 2008 and that working people have not received their fair share of growth.

The focus is on boosting productivity and ensuring that the rewards of that productivity gain are widely shared.

This focus on productivity and the language around it, reaches back 50 years to Harold Wilson.

Labour today have argued that Britain needs an "industrial strategy" to achieve a "national renewal".

The policies outlined range from setting up an Infrastructure Commission, to establishing a state-owned British Investment Bank, to boost lending to small firms, to working with employers on apprenticeships and skills policy.

This all has the familiar ring of Wilson's "white heat of technology" approach and sitting behind that is the idea that the government - through interventions and setting up new institutions - can shape the economy's outcomes and boost productivity.

The impression one gets reading through much of the policy is that Labour want to reshape the nature of British capitalism, making it a bit less American and a bit more German or Swedish.

Those northern European economies are often held up as examples of states that have cracked the secret of ensuring that there are enough high skill, high productivity jobs to support good wages and high living standards.

Compared to Anglo-Saxon economies, they offer a more "ordered" and less free-flowing model of capitalism.

While they are by no stretch centrally planned, they are also very different from the UK's own model of shareholder primacy and very flexible labour markets.

Setting out to change the UK's national business model is an extraordinarily ambitious agenda.

The last example of this kind of achievement was under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.

But there are three potential problems with this approach.

No sweeping policies

First, there are those who will note that the grand rhetoric of "national renewal" is not matched by similarly sweeping policies.

For example, boosting the minimum wage to £8 an hour by 2019 and encouraging firms to pay the living wage is not quite the same as ending low pay in general.

The policies announced today are mainly, fairly modest - in short they might tweak the British economy rather than fundamentally change it.

Could we end up with something resembling the French economy?

Second, it is far from clear that the policies outlined would boost productivity at all.

Economists have spoken of a "productivity puzzle" for several years now, which is a polite way of saying, "we haven't got a clue why productivity has been so weak."

Everyone agrees that productivity is important but there is no real consensus on how to increase it.

It's not as if previous governments haven't tried to boost productivity - there is no single Whitehall lever that can be pulled.

And finally, attempting to change the national business model, or remodel British capitalism, could have unintended consequences.

A few years ago I heard one Scandinavian policy maker remark: "The road from London to Berlin runs through Paris. Be careful not to get stuck."

The worry is that by attempting to replicate, even to a limited degree, the kind of co-ordinated institutions that shape the economy in Sweden or Germany you end up with something that looks rather more like France - a less flexible economy prone to higher unemployment.

The attention for the last few years has mainly been on Labour's demand side economic policy - more spending - but in the longer run, their supply side policy of economic reform may be more important.