When will the Fed raise rates?

- Published

How urgent is action on rates?

The Federal Reserve, the US central bank is going to raise interest rates. We don't know when, and the truth is that it's unlikely to be at the meeting that concludes on 17 June.

But it will come and the women who are arguably the world's two most powerful economic officials have different views about when it should be.

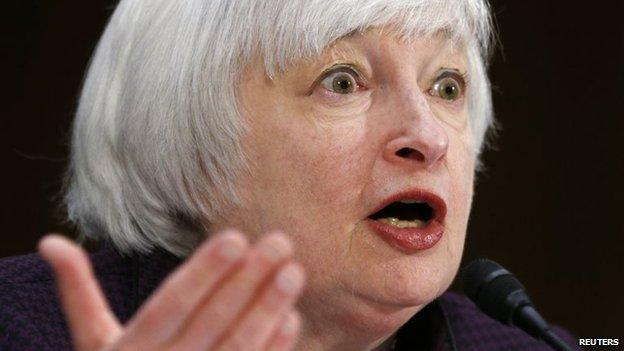

The Fed Chair Janet Yellen said in March, external:

"I expect that conditions may warrant an increase in the federal funds rate target sometime this year."

But Christine Lagarde, the IMF's Managing Director said, external "we believe that a rate hike would be better off in early 2016".

But it is not Ms Lagarde's decision and betting is that it will be later this year. The September meeting is thought to be a strong candidate. So what is going through the minds of the men and women who set interest rates in the US, the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) at the Federal Reserve?

What is Janet Yellen thinking?

The job, external of the FOMC, which Ms Yellen chairs, is to guide the US economy towards "maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates".

They think , externalthat the US is close to the level of unemployment that is sustainable over the long term - somewhere between 5% and 5.2% is what most of the committee think that is - and the current unemployment rate is 5.5%.

The IMF's Christine Lagarde thinks the Fed should wait until next year to raise rates

When unemployment goes below the sustainable level, it can start to generate more inflationary pressure.

So the US is close to that level, though the jobs market is perhaps not in quite the rude health that number suggests.

There are still many people not officially counted as unemployed, because they are not looking for work, who would nonetheless like a job. They are known as discouraged workers.

Then there are people working fewer hours than they want. Add in these people and you get a figure with the rather ungainly title of "labour underutilisation". As recently as February, the Fed said, external in its twice yearly report to Congress this figure "remains quite elevated".

Then there's inflation. It's low, comfortably below the Fed's 2% target. It will probably rise if the jobs market continues to strengthen, but its current level is another reason the Fed is no hurry to raise its main interest rate target back to a normal level.

Whatever that normal level for Fed rates is after the drama of the financial crisis - and many think that will be lower than it was before - the process of getting there will, as Fed Chair Janet Yellen has said, be "gradual", external. It will take a long time to get there.

How will the markets react?

Even if the journey back to normal interest rates hasn't yet started, the impact on the financial markets is already evident.

Indeed the speculation about when and how quickly the Federal Reserve will move has perhaps been the biggest single preoccupation of global financial markets this year - though it is conceivable that the situation in Greece could yet knock the Fed back into second place.

The impact has been most evident in governments' borrowing costs. This is where debts are traded. Governments and also big companies borrow money by selling bonds - a kind of IOU.

Investors buy these bonds to receive regular interest payments and a lump sum at some date in the future. These cash flows, combined with price the investor pays, give the bond's yield, in effect the interest rate they get for lending money to the government or whoever issued the bond in the first place. When a central bank raises its official interest rates, those yields tend to rise as well.

And that is what has been happening as investors anticipate a move by the Fed that is seen as inevitable at some stage.

The US economy has created hundreds of thousands of jobs, so is the time right to raise rates?

Take US government Treasury bonds with 10 years to go before they mature, when the big final repayment is made. The yield on them is now 2.3%, up from 1.6% at the end of January. Still low, but the impact of possible Fed action is there.

Other markets have been affected too. Ten year Turkish government bonds, for example, now yield 4.8%. The figure was 3.9% at the end of January. The Turkish currency has fallen by 15% against the dollar in the same period as investors have switched to US bonds.

Should we expect a rocky road ahead for markets?

It could all happen smoothly. But the IMF did warn in April, external there's another possibility: "a bumpy ride with… rapidly rising yields and substantially higher volatility".

So we might see some sharp upward moves in borrowing costs far beyond American shores which could be very disruptive for emerging markets. We had a taste of this in 2013, external, in an episode that came to be called the taper tantrum.

That was when the previous Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke signalled that the Fed was considering scaling back its quantitative easing programme of buying financial assets with newly created money.

That process is complete and it was an important stage in getting Fed policy back to normal after the exceptional steps it took in the wake of the financial crisis. Starting to raise interest rates will be next one.

- Published5 June 2015

- Published25 May 2015