The sticky dilemma facing chocolate firms

- Published

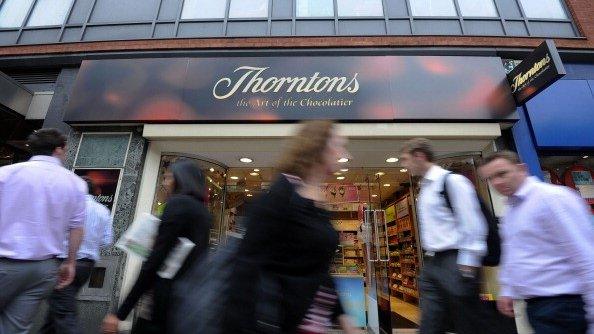

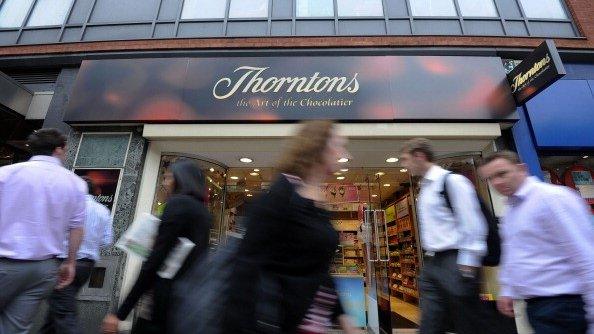

Thorntons' shop on London's Oxford Street is quiet on a hot June afternoon

The Thorntons shop on London's Oxford Street - one of London's most popular shopping districts - is looking a bit worse for wear.

The floors are grubby and almost everything there, crammed tightly into every available nook and cranny, appears to be on sale or part of a bulk buy special offer.

The sole customer on a hot June afternoon is an Italian tourist, who buys a huge bag of chocolate which she says is "for presents".

The store appears more akin to a discounter, a place for bargain hunting, and offers no obvious improvement on buying the products in a supermarket.

This, say critics, is exactly the high street chain's problem. Its products are sold so widely - in supermarkets and even in newsagents - that it appears mass market, yet its prices suggest a premium product.

Thorntons new owner has to choose whether to continue to focus on supermarket sales or move more upmarket

'Motel Chocolat'

And it's the problem which Thorntons' new owner, Italian firm Ferrero, will have to address, assuming shareholders agree to the £112m offer which its board has recommended.

The deal, if it is completed, will enable Ferrero to step ahead of its Swiss rival Lindt to become the UK's fourth-largest chocolate brand, behind Mondelez, Mars and Nestlé, giving it a near 7% UK market share.

But Ferrero will have to decide what to do with that market share. Should it continue with outgoing chief executive Jonathan Hart's already well-advanced plan of reducing the number of shops, and instead focusing on wholesale sales - the cheaper end of the market? Or should it try moving the brand more upmarket?

Put simply, says independent analyst Nick Bubb, it's a choice between continuing to be "Motel Chocolate" or Hotel Chocolat.

The competition between Thorntons and its upstart Hotel Chocolat rival was once so intense that in 2007 Thorntons' then top chocolate maker, Barry Colenso, was forced to resign, external after being caught squashing truffles in one of Hotel Chocolat's stores.

Thorntons' rival seems to have caught and overtaken the older brand. Recently, Hotel Chocolat reported a £6.6m pre-tax profit for the six months to 28 December, beating Thorntons' £6.5m profit for the half year, despite having just 81 stores compared with the latter's 242.

A chunky problem

The firms' diverging fortunes illustrate the wider problem facing the British chocolate industry. People may like chocolate, but, in the UK at least, they're eating less.

UK chocolate sales grew by 1.6% last year to just over £4.1bn, but the amount of chocolate sold fell 1% to 437 million kg, according to market research firm Mintel.

In the meantime, the costs of core ingredients such as cocoa and palm oil have increased, putting more pressure on chocolate firms.

With the amount of chocolate people are eating unlikely to grow, manufacturers are under pressure either to cut costs or put up prices.

Some firms, such as Cadbury creme egg owner Mondelez International, are offering less to cut costs

Mass market brands such as US firm Mondelez have taken the drastic step of offering less product for the same money. For example, this year the group said that multi-packs of creme eggs would contain five rather than six eggs due to "economic factors".

But other firms have tried to make their products more upmarket so they can charge more money for them, says Euromonitor food analyst Jack Skelly.

"It's hard to get people to eat more chocolate, so the idea is to increase value sales by making a more premium product," he says.

He points to Cadbury's decision to make pouches containing chunks of some of its most popular bars, such as Wispa and Twirls, which he says have a more expensive and bulky feel. This then allows the firm to charge a bit more.

Ultimately, Mr Skelly says all firms need to decide which audience they're targeting: the hungry impulse buyer in a local newsagent, or the more discerning customer who treats chocolate as a luxury.

"For a firm which wants to make billions of dollars globally, it's about getting it sold in as many different stores of possible; for a lower scale product it's about getting the brand message across," he says.

Chocolate is seen as a luxurious treat by many, an association, experts say chocolate firms should encourage

But for a product like chocolate, deemed a treat by many, it seems a significant number of people are willing to spend more for a spot of indulgence.

More than a third of British chocolate buyers splash out on premium products either "regularly" or "all the time", according to market research firm Canadean, external.

"Irrespective of their financial situation, consumers are still willing to trade up on a regular basis in categories inherently associated with treating and indulgence," says Canadean research manager Michael Hughes.

To take advantage of this, manufacturers need to push the luxury concept to make consumers "feel they're getting a real treat", he says.

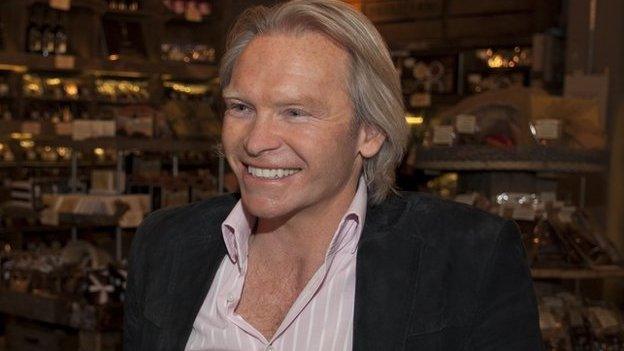

Hotel Chocolat founder Angus Thirlwell says the chain's aim is to make people feel good about eating chocolate

'An emotional experience'

Hotel Chocolat co-founder and chief executive Angus Thirlwell says that's exactly what his company has aimed to do.

"It's an emotionally charged food product that people are buying for the taste and the way it makes them feel," he says.

To capitalise on this, he says the chain has focused very carefully on ensuring a high cocoa content in its chocolates, and making its stores feel like a "sanctuary" providing "escapism" for customers.

While Mr Thirlwell's aims may sound a bit lofty - it's just chocolate after all - the firm's growth into a multi-million pound empire, with 81 shops, eight cafes, two restaurants, and a hotel, in just over a decade, suggests he's on the right track.

Hotel Chocolat has also been careful about its distribution network, he says, selling through its own stores or selected partners, such as John Lewis, that fit the brand's values.

The intention, he says, is to make people feel good about eating chocolate, so that it becomes "an emotional experience" rather than just something to "munch".

Hotel Chocolat has focused on having a high cocoa content in all its chocolates

"We started with a basic premise: let's distribute it in a way that will make people feel good about buying chocolate, so not in a commoditised way," says Mr Thirlwell.

This approach extends to store openings, which he is happy to grow at a "natural pace", he says.

"Certainly we want to strike the right balance, between making our creations sufficiently available but not so ubiquitous that they become a commodity. It's a real treat to savour and enjoy, and if they become too widely available there's a risk that could diminish."

- Published27 October 2014

- Published22 June 2015

- Published2 March 2015