Is austerity the answer to economic downturn?

- Published

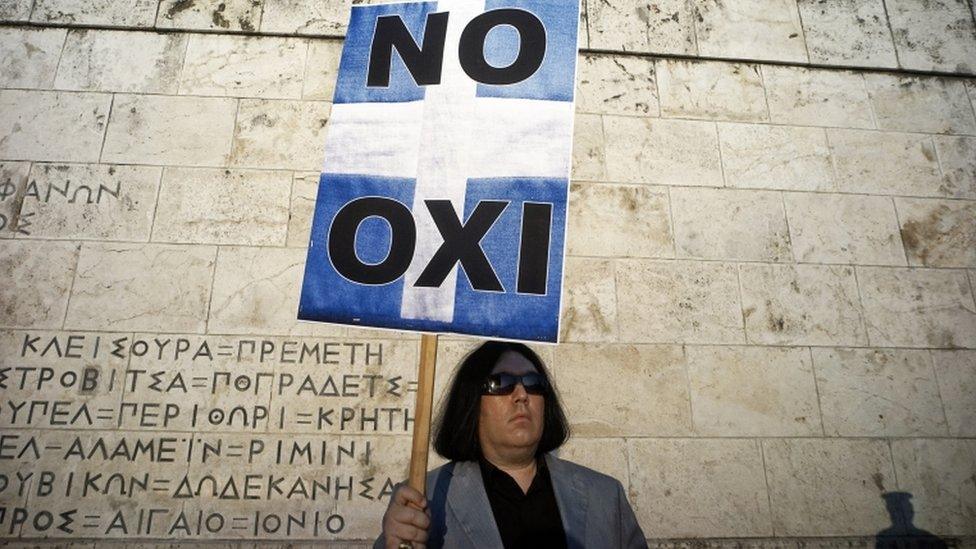

Anti-austerity protests have taken place across the world

At the heart of the current Greek debt crisis is an old debate - is it better to cut spending and raise taxes in an economic downturn, or spend your way out of it?

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras came to power on a wave of public anger over austerity measures, and he is urging the Greek people to vote against austerity once more in a snap referendum on the country's debt crisis to be held on Sunday.

Meanwhile tens of thousands of people took part in anti-austerity demonstrations across the UK in June despite the government's insistence that austerity measures are vital to cutting the deficit.

Many countries decided to cut spending and put up taxes to deal with the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis. Were they right? Has austerity worked? Four experts offer their assessment.

Stephanie Flanders: Damned if you do, and damned if you don't

Former BBC economics editor Stephanie Flanders is now chief market strategist for JP Morgan Asset Management.

"In 2009 we suddenly found ourselves in a much steeper recession than people thought, and the impact was suddenly very clear on the public finances. It pushed up budget deficits all over the world - particularly in the UK - by tens of billions.

International leaders used the 2009 G20 summit in London to broker a co-ordinated global stimulus

"No one was making any money or paying any tax, meanwhile the unemployment numbers were going up quite quickly and that was pushing up costs. There was a moment leading up to the G20 summit in London in 2009 where leaders said 'we've got to have a global co-ordinated stimulus'.

"They were all on one side saying, 'we've got to not worry too much about borrowing going up, because governments are the only ones who can afford to do this at a time when households and companies are also cutting back'.

"[As a result] you saw the start of a recovery in most countries, and at the same time these horrendous borrowing numbers were coming in which we hadn't ever seen in peace time. And there were mutterings: 'Hang on, we're going to face an awful lot of pain to get that down, shouldn't we start doing that now?'.

"So they faced that dilemma: 'we've saved the economy, how quickly do we start to raise taxes again and cut spending to get our public finances in order and how quickly can we afford to do that without hurting this still fragile recovery?'

"If you think the economy is going to carry on growing, then you want to take a bit of that growth and start to put it back into the government coffers.

"You want to have taxes going up, certainly some plans to rein in spending, but of course the contrary argument is you can't assume that growth, because some of it is coming from what you're doing to prop up the economy.

"Unless you know that there's going to be other demand out there to make up the gap, you might face the economy slipping back into recession and then the borrowing is going be even worse.

"If the international lenders start to worry about whether you're going to pay it back, they start to charge you more interest, and if they charge you more interest, then your interest rates of course go up, and that pushes up your borrowing as well - you might be damned if you do, and damned if you don't.

Philip Coggan: Too much austerity can be counterproductive

Philip Coggan writes for The Economist.

"Most people think of being austere as living a very quiet life, not spending too much, especially not spending more than you earn. But that's not what economists mean by austerity. Economists mean the change in your financial position.

"Britain went from spending 11% of GDP more than it earned in one year to 9% of GDP more than it earned. That is still doling out money to the rest of the economy, but technically the change of position means that they're cutting spending, or raising taxes, and that makes the policy austere.

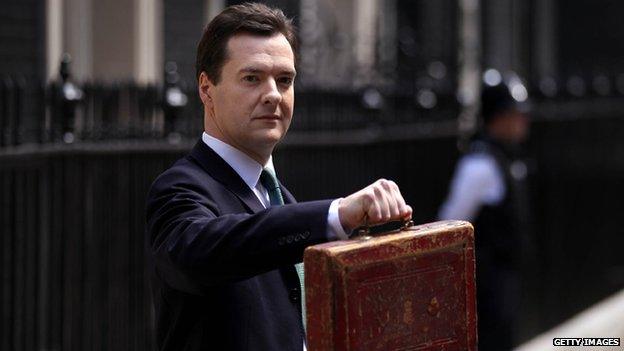

Chancellor George Osborne increased VAT from 17.5% to 20% in his first budget in 2010

"There was one big tax rise - VAT - at the start of the parliament, and then there were big cuts to capital spending on new schools, new hospitals, new roads.

"[Austerity] was very strong for the first two years, so up to the middle of 2012. From that point on, the amount of austerity - the amount of cutting - slowed quite significantly. Some people argue that the government changed tack, and to the extent that the UK economy recovered, then that was all down to this change of tack.

"I don't think we can absolutely sure [whether austerity worked]. To have a proper scientific experiment, you need a control, in which case you need to rerun the economy without what the government did and see what happened. Alas we can never do that.

"The experience in Europe suggests that too much austerity can be counterproductive, and we've seen that in Greece, where the overall economy has shrunk by 25% over the last four or five years, because foreign creditors have made Greece cut back. That does seem to have overdone it.

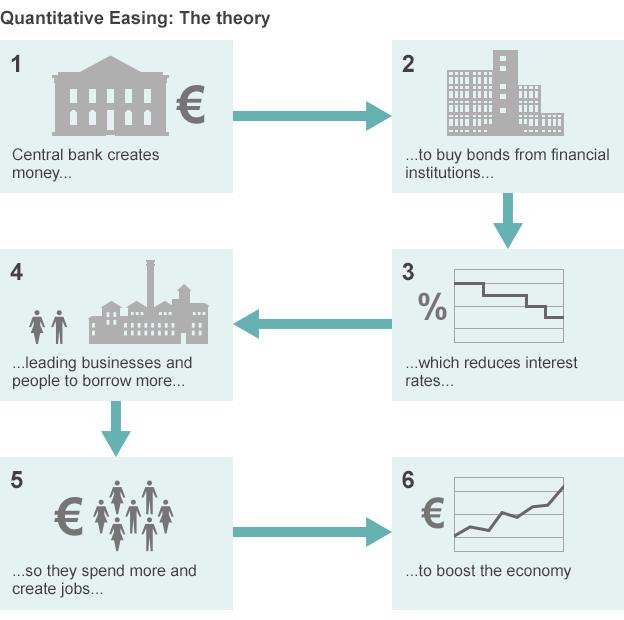

"Some people say, if you have a central bank that's willing to do [quantitative easing: effectively printing money], you don't have to worry about the budget deficit. You can print as much money as you like, you can raise as much debt as you like, and indeed you should do so while rates are so low and spend it on infrastructure projects.

"Would the Bank of England have been willing to do that if the government had said it wasn't bothered about the level of the public sector deficit? Remember it's an independent bank. If you go back to 2010 and see what the [then] Bank of England governor Mervyn King was saying, he didn't give that impression.

"So I think it's a bit optimistic to say that the government in 2010 could have done absolutely nothing and got away with it."

Justin Wolfers: Repaying stimulus debt slows future growth

Justin Wolfers is professor of economics at the University of Michigan, where the US federal government followed a policy of economic stimulus for a little longer than the UK.

"The relevant question for the US is whether stimulus worked.

Lehman Brothers was once the fourth largest investment bank in the US

"Lehman Brothers collapsed, unemployment was soaring, and the Obama administration passed the Stimulus Bill. That was a big part of what supported the economy through 2008, particularly 2009 and 2010.

"At that point quite a lot of the other economies in the world began to pull back on the extent of the stimulus that they were putting into the economy.

"Essentially the US just let its Stimulus Bill lapse. So what had been supporting the economy through 2009 and through 2010 went away. But there was no concerted effort to immediately or swiftly reduce the public debt. The view was that we should let the economy try and recover.

"The big Stimulus Bill for 2008, 2009, 2010 had specific formulae which ended up giving different amounts of stimulus to different states. You can look at those states which happened to get a bigger chunk of stimulus. Did their economy subsequently outperform other states over the next few years? The answer is yes."

"The really big costs are about repaying the debt. We do have a higher debt than we used to have, that gives us higher interest payments each year, and that's a real burden, and it's a burden that will slow growth in the future.

"Borrowing from the future just brings spending from the future to the present, and so there is a real cost, and it's one to be taken quite seriously."

Sir Charles Bean: 'Austerity' debate really about the size of the public sector

Professor Sir Charles Bean was deputy governor at the Bank of England during the financial crisis.

"It's easy to forget the external dimensions. Obviously for the UK, what's been happening on our doorstep in the eurozone has been an important factor on the development of growth here.

"Arguments over 'well, if the government had adopted less aggressive fiscal consolidation we would have grown faster' - and the fact that we saw very little growth during 2011, 2012, reflected that fiscal choice - ignore the fact that across the Channel we were seeing this downturn in our primary export market.

"The question of austerity is often used as a bit of a code word for other, deeper differences of view about the role of the state.

"Often when people talk about austerity, they're not really talking about just getting the budget deficit down, they're actually talking about the size of the state. People who object to it are basically saying they want a bigger public sector.

"That is a big fundamental question. You can have a big public sector, providing it's paid for with higher taxes. There are costs and benefits of that. There are some states that have relatively large public sectors: the Nordic countries have perfectly reasonable growth rates. There are other countries that have smaller public sectors. Some of them have good growth, some don't.

"The question about the size of the public sector, though, is something that is distinct from the question of the appropriate pace of fiscal consolidation after a budget deficit has opened up, in this case as a result of the financial crisis.

"In principle, somebody who's committed to a small public sector could accept, temporarily, a very large increase in public spending during a deep recession, but in practice, it is usually quite difficult to change direction."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT/13:05 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published30 June 2015

- Published30 June 2015

- Published20 June 2015

- Published1 April 2015

- Published28 January 2015