Is austerity saving or sinking Brazil's troubled economy?

- Published

Protestors have gone on the march both for and against government policy in recent weeks

Recent media headlines have focused on the corruption scandal threatening to bring down Brazil's government. But for most Brazilians just as worrying is the state of the economy. Official figures suggest the economy is slipping into recession, and set to contract 2% this year.

When I meet Fabiano Amaral and Graziela Silva they are each holding the corner of a banner in the midst of a crowd of protesters in Sao Paulo.

While people usually take to the streets to complain about their government, the people around us this time are here to show support for Brazil's beleaguered President Dilma Rousseff, facing a political crisis and calls for her impeachment.

Despite their show of support, Fabiano and Graziela aren't unequivocally positive.

"I've been affected by government cuts. I lost my job and had no access to unemployment benefits", Fabiano tells me.

He worked for a little more than six months in a car body shop, but was sacked and has not found a job since.

Austerity drive

Until last year, Fabiano would have had full access to unemployment benefits.

But since January, Brazil's Finance Minister Joaquim Levy has been on a drive to fix Brazil's troubled economy through austerity measures.

That means spending less on unemployment benefits. Most workers now need to have been employed for a full year to receive government aid.

Graziela and Fabiano support the government in principle but are not happy about the recent austerity measures

Fabiano and his wife are paying the price of Brazil's economic recession - without any benefits or prospects of finding a job soon. Since January, unemployment has risen to 8.3%, from 6.4%.

From boom to bust

After a decade of relatively solid growth, Brazil is technically slipping into recession.

A weekly market survey by the Central Bank suggests the economy will contract 2% this year and 0.24% in 2016.

The country's current economic dilemma is similar to that of many European nations, from Greece to the United Kingdom.

For an ostensibly left wing government like Dilma Roussef's it's a particularly painful decision: in times of recession, should a government spend its way out of crisis or rebalance its finances through austerity?

"Dilma scissor hands - against cuts and removal of our rights" says this protestor's placard

For three years, President Rousseff chose the first path.

As the supercycle of high commodity prices reached an end, and Brazil began to suffer, she chose to give stimulus by freezing energy prices, subsidising oil prices, and giving firms tax breaks for hiring workers.

These measures helped ward off recession and keep unemployment at a record low. But not for long.

Brazil's public debt has now reached alarming levels. Rising unemployment and inflation are slowly undoing the gains of Brazil's boom years. The country may even be about to lose its hard-earned investment grade status.

As Brazil's economic star began to lose its sparkle, the president made an about-face, embracing austerity.

Special number

Finance minister Levy resolved to target one particular statistic: the primary budget surplus - the budget surplus excluding debt interest payments - which he insists must be equivalent to 1.2% of the country's economic output.

He slashed government spending and raised taxes, in an attempt to achieve the 1.2%. Unemployment benefits were cut. All sorts of incentives to businesses - from subsidies to tax breaks - were removed. Investment in infrastructure slowed down.

Only this week the government announced it will shrink 10 of its ministries and close 1,000 public servant posts.

The logic was that with a combination of budget cuts and high interest rates, Brazil's inflation would be kept under check and the economy could slowly emerge out of crisis in a stronger financial position.

Hurting the economy

But austerity doesn't appear to be working any better than the stimulus did.

In a modern factory in Sao Paulo, machines are spinning threads into textiles that are sold to the fashion industry. Electricity does all the hard work here.

Renato Bitter, the owner of Savyon Textiles Industry, tells me his energy bill went up 70% since last year, when the government stopped subsidising prices.

"Of course we had to review our prices to our customers and our profits. But we have to keep selling. We have no other choice", he says.

Renato Bitter is one of the luckier business owners having found new markets overseas

Savyon is lucky to have a way out. Brazil's currency has fallen sharply in value, and the firm is now exporting with a competitive price abroad, rather than selling domestically.

But other businesses are having to lay off workers and shut down production.

Government tax revenues flowing into Mr Levy's budget coffers are dwindling.

Now the government has abandoned its budget surplus target of 1.2% replacing it with a more modest one of 0.15%.

What next?

So if stimulus did not work and austerity is not going as planned, what are Brazil's options?

Economists are divided.

In the past year, two contrasting manifestos were signed by Brazil's top academics. One asks for a return to stimulus policies; another says austerity should be maintained.

"Austerity has worsened recession, unemployment, inequality and the fiscal situation of developed countries", argues the pro-stimulus manifesto.

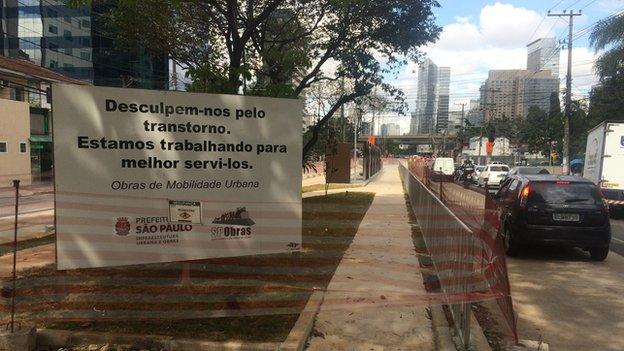

Investment in infrastructure like cycle paths has halted

It says that austerity measures should be delayed until the economy starts growing again.

But the president and Mr Levy are keener on the pro-austerity manifesto, that says that if Brazil does lose its investment grade, inflation and unemployment will rise even further, as international borrowing costs will go up.

"Brazil's problem right now is that it does not have much of an option", says Cristiano Romero, a columnist in Brazil's main business newspaper Valor Econômico.

"It does not have enough tax revenues to stimulate growth through spending, nor has it been able to implement its austerity the way it wanted."

President Rousseff might have thought she could cut spending without damaging the economy. But, as one Brazilian saying goes, the cure is now at risk of "killing the patient".

Now with the chill wind blows across the Pacific from China, an economic partner that Brazil has grown to rely on in recent years, things are only likely to get worse before they get better.

- Published3 August 2015

- Published23 June 2015

- Published12 June 2015

- Published22 April 2015