Would Corbyn balance the books?

- Published

- comments

The new Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell

Labour's new shadow chancellor John McDonnell is not - to quote him - a "deficit denier".

In a blog that he wrote about Jeremy Corbyn's economic policies just a few weeks ago he wrote that, external "deficit denial is a non-starter for anyone to have any economic credibility with the electorate".

And he added that "Labour under Jeremy Corbyn is committed to eliminating the deficit and creating an economy in which we live within our means".

So presumably they'll be cracking open the Krug in the boardrooms of Britain and the well-appointed Kensington drawing rooms of the super-rich - it's all been a terrible misunderstanding, Red Jezza is more delicate rose than scarlet, he is on their side after all...

Er, no.

John McDonnell is unambiguous that "we believe that we can tackle the deficit by halting the tax cuts to the very rich and to corporations, by making sure they pay their taxes, and by investing in the housing and infrastructure a modern economy needs to get people back to work in good jobs".

On companies, for example, he wants to make cuts to what he calls the £93bn in subsidies to corporations.

Now this £93bn of putative handouts to business was estimated by Kevin Farnsworth, a lecturer at York University, external, for the Guardian.

Whether or not this is a robust statistic, it is certainly a huge number.

It is, for example, considerably more than double the £43.1bn the Treasury expects to raise in total from companies in corporation tax this year.

So Mr McDonnell is putting business on warning that they should expect a very substantial increase in their tax burden under a Corbyn administration.

He also makes clear that Labour would increase the minimum wage, rebranded by the present chancellor as the "living wage", considerably more than even the increment promised in George Osborne's last budget.

There would be reductions to "subsidies paid to landlords milking the housing benefit system" - presumably from rent controls.

Banks would be formally broken up into separate high street and investment operations, as opposed to the firewall or ring-fence to be erected between these activities under the current government's plans.

City firms would also be subject to a financial transactions tax, of the sort that George Osborne has been fighting off in Brussels.

Companies in general would be obliged by law to adopt "long-term sustainable and social responsibilities" as their "prime objective".

And there would be an "extension of a wider range of forms of company and enterprise ownership, including public, co-operative and stakeholder ownership".

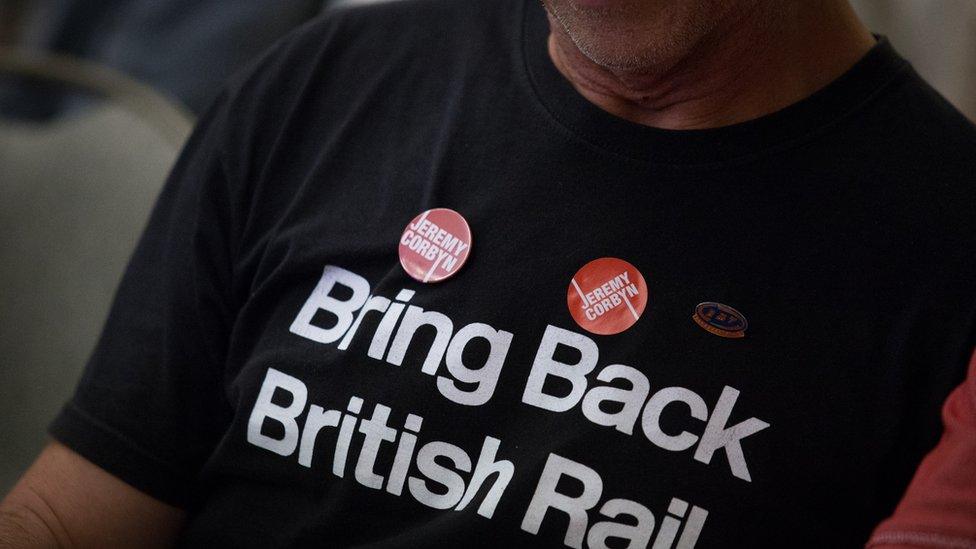

As for the promised re-nationalisation of the railways, this would take the form of "joint management involving workers and passenger representatives".

Rail re-nationalisation is one of Jeremy Corbyn's key policies

But in gas and electricity, Mr McDonnell talks about "removing the monopoly of the big six energy companies" - as opposed to taking them into public ownership - via "massive expansion of renewable energy production and supply by local communities, local authorities and co-ops".

Now what is unclear is how and whether Mr McDonnell would push through Jeremy Corbyn's most eye-catching policy, namely so-called "quantitative easing for people not banks" - or the plan to oblige the Bank of England to make cheap loans to a new state-owned investment bank, which would then use the finance to invest in transport, housing, energy and digital infrastructure.

I wrote a fair chunk about people's QE a few weeks ago. And the big unresolved question about the policy is whether it is supposed to be a policy tool for recessions or a permanent flow of cheap money for socially worthy projects.

As John McDonnell presumably knows, if the Bank of England were mandated to supply cheap loans forever and a day to finance investment in the fabric of the UK, most economists believe that - inter alia - the Bank of England would be perceived to have been transformed once more into a pawn of government.

And at that ill-starred juncture, investors would charge massively more for lending to the UK - our interest rates would rise sharply - because the Bank of England would no longer be trusted to maintain the value and integrity of sterling.

John McDonnell may find that the economic credibility he so wishes to establish with voters requires more than a pledge to eliminate the deficit by soaking the rich.

All in all, Corbynomics, as interpreted by John McDonnell, represents pretty muscular socialism - with a strong green flavour - of a kind we haven't seen practised in government in the UK since at least the 1970s.

Whether it is practical in the absence of capital controls, to prevent money fleeing the UK, is one question Mr McDonnell will presumably want to answer reasonably prompt-ish.

And even if there were not a panicked exodus of capital from the UK, the role of the state as an employer and investor would increase substantially - because it is inconceivable that the private sector would willingly invest more when the costs of doing business in the UK would be forced up very considerably.

Many of course trust the state far more than they do the private sector. But whether a majority of voters will ever again vote for the idea that politicians make better decisions than markets is the big question posed by Corbyn's victory.