Should Fed raise rates now?

- Published

- comments

Janet Yellen, the US Federal Reserve Board chair

There is never going to be an easy, risk-free time for either the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England to push up interest rates.

The decision on whether to raise or cut rates is rarely simple. But it is especially tricky given that for almost seven years official rates in both countries have been so close to zero as makes no difference.

What matters is that there has never been any time in recorded history when the cost of money has been so cheap for so long.

And although in theory it should be seen as good news when rates rise, because it means that the central banks (who are after all paid well to know about these things) judge that our economies are getting back to health, we can't know for sure whether turning off life support is just what the doctor ordered, or will cause palpitations and even a cardiac arrest.

Which is why it is both a privilege and a heavy responsibility for Janet Yellen and her colleagues on the Fed's Open Market Committee to decide over the next couple of days whether or not to announce on Thursday that the era of almost free money is officially over.

For what it's worth, markets are betting that the Fed will delay a bit longer - because of uncertainties about the impact on the US economy of the pronounced economic slowdown in China and emerging economies.

But the Fed might, per contra, decide that what matters more is the relatively robust performance of the US economy - where jobs are being created at a relatively healthy rate, unemployment has nudged down to 5.1%, business investment is strong and growth estimates have been revised up.

They could conclude that, after months of warning that rates are to rise soon, if they delay any longer they will be trapped in some interminable monetary version of Beckett's Waiting for Godot - till they too are seen to be as ridiculous and hopeless as Vladimir and Estragon.

But if the Fed's members are indecisive, it is difficult not to sympathise.

In the opaque globalised financial world, they know that all sorts of bubbles and market distortions have been created and pumped up by the steroids of super-cheap dollar debt - but they can't be certain of the scale or even the precise location of these unhealthy imbalances.

The point is that because the dollar is the world's currency in a way that is true of no other, when US interest rates are low, companies, governments and even individuals have a huge incentive to borrow big sums in dollars.

This has indeed come to pass. Earlier this week the Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers' central bank, warned that the total amount of dollar loans to borrowers other than banks outside the US had risen since the beginning of 2009 by more than 50% to $9.6tn.

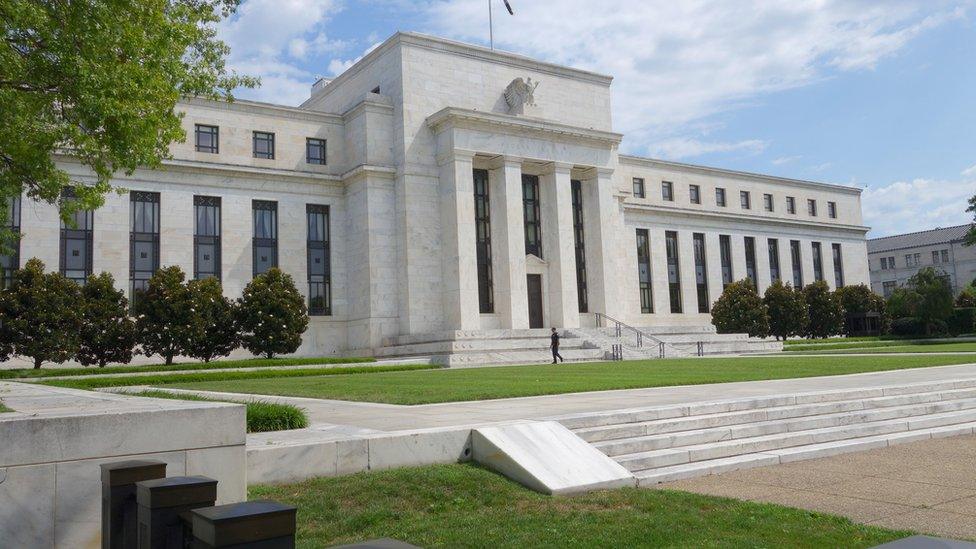

The US Federal Reserve Building, Washington DC

That is a huge amount of cheap credit poured into economies all over the world. It has fuelled investment by businesses. It has been used to buy properties and shares. And it has spurred growth and significant - perhaps excessive - rises in the price of assets.

And of this $9.6tn, more than $3tn had been borrowed by companies and other institutions in emerging economies.

So here is the vice squeezing the half of the global economy represented by emerging economies.

On the one hand, the fall in commodity prices and the slowdown in China is undermining their growth. On the other, the cost of servicing their dollar-denominated debts is rising, because the dollar is strengthening on the expectation that interest rates will rise.

And more than that, the tap of cheap dollar funding is gradually being turned off, which means that the flow of money to these economies has been cut - and by more than just the value of reduced dollar lending, because dollar loans often sit on balance sheets and in banks, and are used to make additional local-currency loans.

Here is the thing.

Even if the Fed has been shouting to the world that rates will rise soon, it cannot be certain that evasive prophylactic action has been taken from Brazil, to Turkey, South Africa and Malaysia. Accidents will happen on the fateful day that the target for Fed Funds rate is lifted, if only by a smidgeon.

And there is no market oracle who can be wholly confident these accidents will be small whoopsies rather than clanging calamities.

One more thing - psychology matters.

As Haldane of the Bank of England has pointed out, we all still bear the emotional scars of the 2008 financial and economic catastrophe.

Who knows quite how anxious we will feel when confronted with the harsh reality that interest rates can rise as well as fall?