Volkswagen scandal: Are car emissions tests fit for purpose?

- Published

The scandal involving Volkswagen cheating car pollution rules in the US has thrown a spotlight on emissions testing - particularly in Europe.

Campaigners have for years complained that the data claimed by manufacturers was a fantasy.

Now, critics have concrete evidence of the lengths that one of the world's biggest carmakers was prepared to go to hide the truth about its diesel vehicles.

That VW's bid to scam the system was revealed in the US, where the diesel car market is very small, underlines that country's more robust approach, says Greg Archer, manager at the international campaign group Transport & Environment.

"They've got a much better system. In Europe, we do not test the right cars in the right way," he says. "In Europe, the cars tested are pre-production models that are specially prepared for the purpose. The industry calls them 'golden vehicles'."

20-minute tests

Europe's tests are governed by the New European Driving Cycle. Despite being called "new" the NEDC was developed in the 1970s, and got its last major revision in 1996.

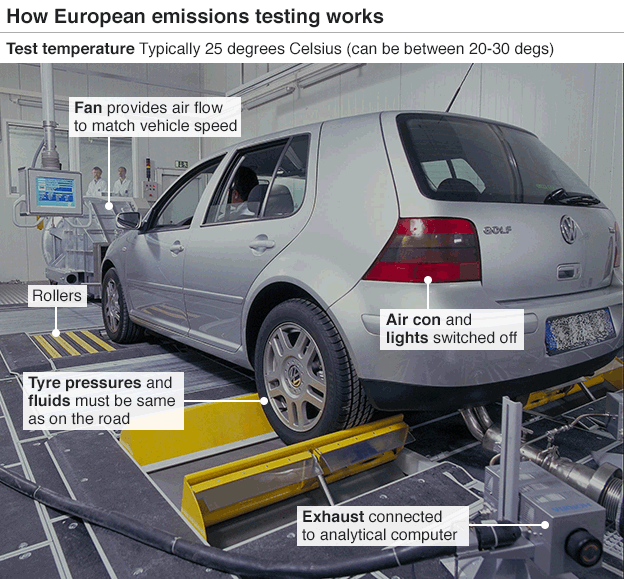

How do you test a car's emissions?

Cars are hooked up to measuring equipment, and go through acceleration and deceleration tests to measure carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter, fuel efficiency, and so on.

Tests are carried out by independent organisations or at manufacturers' own facilities. Either way, the intention is to create a standardised, controlled environment, where temperatures, tyre pressures, fluid levels, braking, and much else can be monitored.

The process is overseen by government-appointed inspectors, who in the UK come from the Vehicle Certification Agency (VCA), to ensure there's no corner-cutting. However, the VCA website, external says it will only "witness some tests being carried out".

The aim is to replicate driving conditions in a busy European city. And this is where the critics cry foul.

Such tests, they argue, replicate little of real-world driving, which is why so many studies have queried manufacturers' emissions data.

For instance, according to a report published earlier this month by the UK Committee on Climate Change, between 2002 and 2014 the gap between official and real-world CO2 emissions for new passenger cars increased from about 10% to 35%.

'Gaming the system'

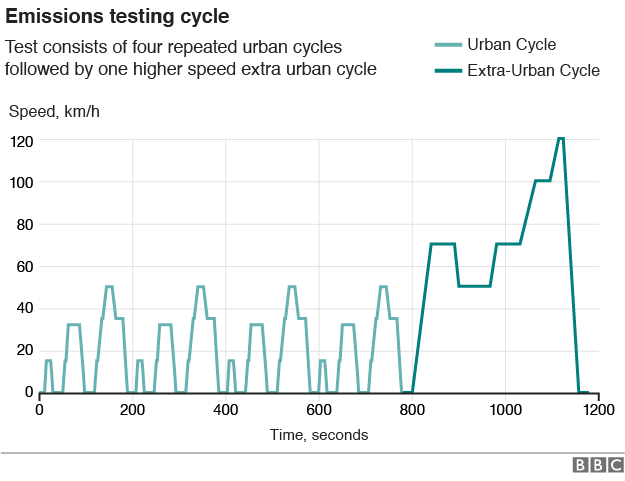

Europe's NEDC test involves putting cars through two cycles, one lasting about 13 minutes at an average speed of 12mph, and a second cycle lasting almost seven minutes at an average of 39mph.

Regulators in Europe were already in discussions with carmakers about new emissions tests

For Jane Thomas, from Emissions Analytics, one of the leading independent emissions analysts, the NEDC tests are "very sedate and short. There is no resemblance to real-world driving".

The gentle acceleration, cruising speed, and braking used in the tests would be unrecognisable to most drivers, she says.

There is no simulation of prolonged motorway driving, and carmakers use the most optimal settings to improve performance, such as the bare minimum of fuel and switching off air conditioning.

She says carmakers might remove windscreen wipers, wing mirrors, and spare wheels, and even tape up doors to reduce drag.

"I don't think manufacturers (in the EU) break the rules, but they do bend them," she says. "Everyone is gaming the tests in Europe."

Even the VCA, on its website, says that "because of the need to maintain strict comparability of the results achieved by the standard tests, they cannot be fully representative of real-life driving conditions". The VCA declined to comment.

Best tests?

The UK trade body for carmakers, the SMMT, denies that car makers modify cars to reduce drag.

"All car components are present, and fluids and tyre pressures are set at recommended in-use levels and vehicle manufacturers do not - indeed cannot - remove mirrors, over-inflate tyres, tape over panel gaps or any such activity to gain advantage in the tests," said Mike Hawes chief executive of the SMMT.

In a statement released on Monday the SMMT said that the European motor industry "accepts that the current test method for cars is out of date, and is seeking agreement from the European Commission for a new emissions test that embraces new testing technologies, and which is more representative of on-road conditions".

In the US, test cycles are longer and more rigorous, including for city driving, on motorways, and aggressive driving. There are also "supplemental tests", including running a car with air conditioning on.

Manufacturers do their own tests and submit reports to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the regulator taking action against VW. If the EPA is suspicious of the results it conducts its own inspections.

Gases

"It's much harder to set the car up to game the test in the US," said Ms Thomas. "The EPA also spot-checks, although they do not do a lot."

There is also an argument that US regulators are prepared to come down harder on firms that breach its rules. In 2014, Hyundai and Kia agreed a $100m (£66m) settlement after under-stating emissions data.

Experts says getting emissions testing right is a matter of public health

Max Warburton, automotive expert at analysts Sanford C. Bernstein, says: "The European standards are easier to meet, so there is less need to cheat.

"The ambiguity of the European rules suggests that even if VW were found to have used complex software to cheat the tests, it would be difficult to fine the company.

"The thing now is, the EU [European Union] and other regulators are going to climb all over [carmakers] and this will speed up the introduction of much tougher tests and rules."

'Very incomplete'

The EU has proposed real-world testing from 2017, with new proposals to close loopholes and adapt to new technologies that allow manufacturers to flatter their data.

The plans, still to be finalised, include using portable emissions meters to identify NOx, and to put on-road cars through a series of tests.

Attempts by Volkswagen to cheat the testing cost chief executive Martin Winterkorn his job

The European Automobile Manufacturers' Association is not impressed. The proposals are "very incomplete", it says, adding that even in the real word, standards of driving differ depending on location, weather, and driving style.

Amid the claim and counter-claim, experts warn not to forget that getting the testing right is an urgent matter of public health.

Prof Alastair Lewis, Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry, University of York, says much public policy is based on the test results.

"The reasons the tests are conducted is ultimately so that air pollution can be managed appropriately," he says. "Emissions data from manufacturers is used by governments to simulate future air pollution levels and set policy."

It was predicated a decade a ago that, for example, NOx in city centres would be on a downward trend, he said.

"But this was based on cars emitting NOx at the rates suggested by the manufacturers' test data, and the reality is that NOx has effectively plateaued in most cities, and in many places is above the European air quality standards."

- Published23 September 2015

- Published23 September 2015

- Published10 December 2015