Air pollution: invisible health threat

- Published

- comments

Walking, cycling and driving - you can see one of the air pollution monitors on my belt

How safe is the air that we breathe? The VW diesel emissions scandal has highlighted the issue of air pollution.

The two pollutants which give most cause for concern are the toxic gas nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter (PM2.5), particles so small they can be ingested deep into the lungs.

Earlier this year the UK's highest court ruled the government must take action to cut NO2 pollution. The UK has been in breach of EU limits for nitrogen dioxide for several years.

Last month the environment ministry DEFRA published a consultation , externalon draft plans to improve air quality.

This places the emphasis on local authorities to improve air quality and would still see Greater London not meeting the required NO2 levels for another 10 years.

The government accepts that the combined impact of NO2 and particulate matter pollution "represents a significant public health challenge".

The Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants (COMEAP) suggests that 23,500 lives are cut short each year by NO2, and 29,000 by particulate matter.

When I spoke to Frank Kelly, Prof of Environmental Health, King's College London and a member of COMEAP, he stressed that you can't simply add the two figures together to get the total effect - there will be some overlap.

Furthermore, he pointed out that new - more accurate - mortality estimates will be released by COMEAP in December.

Prof Kelly was nonetheless adamant that "tens of thousands of lives" in the UK are ended prematurely by air pollution every year.

He told me: "Air pollution is second only to active smoking as a public health threat, and in the past decade we have greatly increased our understanding of its dangers."

A black carbon monitor (left) and PM2.5 monitor

It is worth pointing out that you won't find air pollution listed on any death certificate.

Rather, these are lives cut short by heart disease, stroke, lung disease or cancer that are triggered or exacerbated by pollutants.

In city centres most of that pollution is coming from traffic, and diesel engines produce far more NO2 and particulate matter than petrol.

Prof Kelly's team at King's lent me two personal monitors so I could try to get a sense of what level of air pollution people are ingesting.

I walked, cycled and drove down Brompton Road in Knightsbridge, one of the busiest and most exclusive shopping streets in London.

I chose this because Kensington and Chelsea is, according to Public Health England,, external the most polluted borough in the UK.

One monitor measured PM2.5 - in a congested London street, most of this pollutant would be from vehicles, especially diesel.

The other measured black carbon - the sooty emissions from diesel engines.

I felt a bit self-conscious carrying these rather bulky items, complete with plastic tubes which "sniffed" the air.

But none of the hundreds of people I passed seemed to notice, or they were too polite to say anything.

There is no safety limit for either pollutant - rather the lower your exposure, the lower the risk of harm.

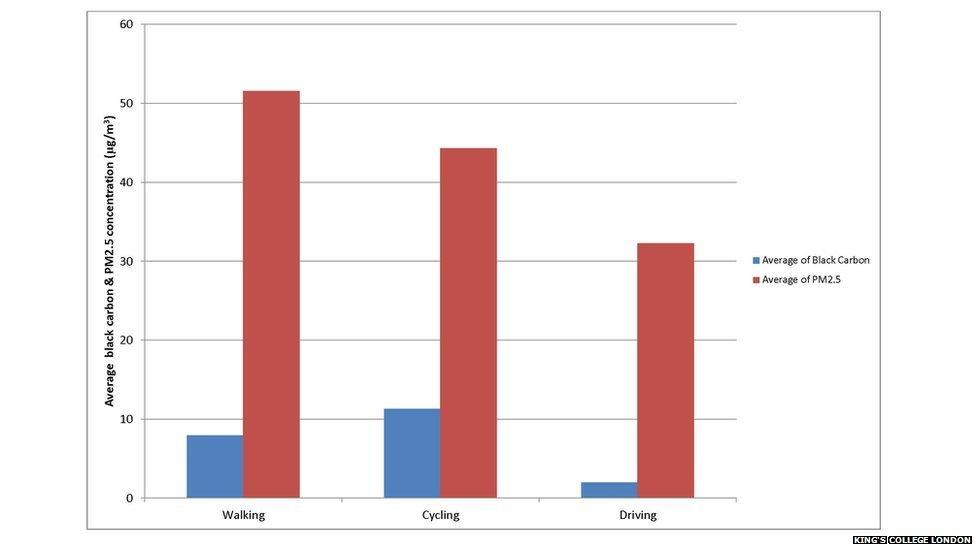

I spent around 30 minutes on each mode of transport and the broad findings were these: for black carbon the highest level of pollution was whilst on a bike, followed by walking, with the lowest level while driving.

All of pollution levels I was exposed to here are higher than the London average

For PM2.5 it was - walking (highest), followed by cycling and driving.

The findings surprised Dr Ian Mudway, a lecturer in respiratory toxicology at King's College London.

He told me: "Normally when we do this experiment, the levels for passengers in taxis or buses are higher than for cycling or walking. This suggests that this particular car has really effective filters - good for you but not for others breathing in your emissions."

All the results were in ug/m3 (micrograms per metre cubed):

For black carbon I averaged 8.0, 11.3 and 2.0 while walking, cycling and driving.

To put that in context the figure away from a busy road in London is around 1.0.

The PM2.5 monitor showed an average of 51.6, 44.3, and 32.3 while walking, cycling and driving.

On a quieter road, the figure would be around 20.0.

The problem is that such figures are pretty meaningless to the public, and apart from a bit of a cough I felt no ill-effects from spending a few hours going up and down Knightsbridge.

Dr Mudway told me: "This is the big challenge because when we tell people about the tens of thousands who die prematurely as a result of air pollution, they can't tangibly appreciate it - it's not like people are dropping dead at the bus stop when a bus goes past. Rather these are the cumulative effects of air pollution over time."

What struck me from my few hours with the air monitors, was how dramatically pollution levels dropped off once I went away from a busy road.

So if you can, it is worth seeking out quieter roads while walking or cycling - the exercise is good for you, and the air will be less polluted too.

- Published10 April 2014

- Published16 July 2015