Will China's economic slowdown be a bumpy ride?

- Published

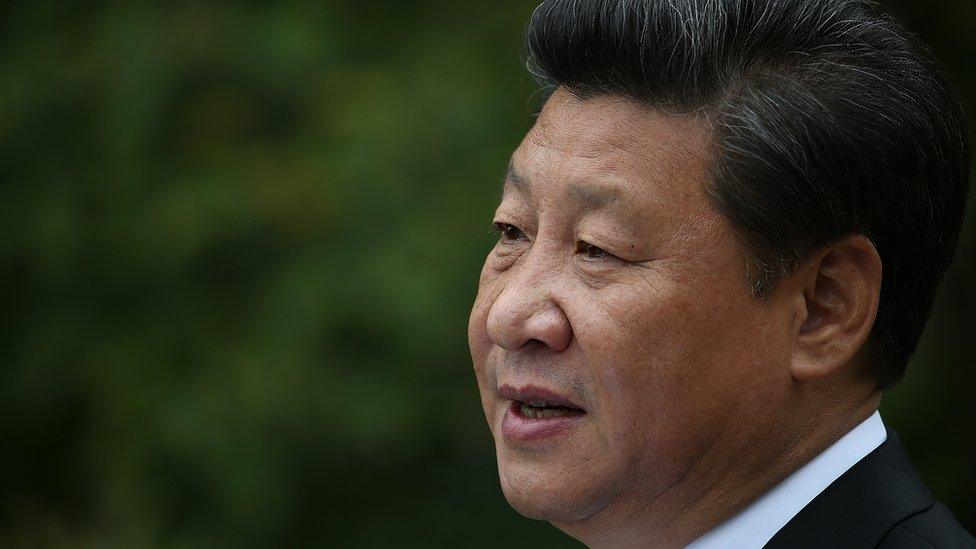

Xi Jinping's visit to the UK coincides with the release of the latest data on the Chinese economy

The Chinese President Xi Jinping comes to the UK this week.

It's a formal state visit. He will be the Queen's guest at Buckingham Palace.

There will be plenty of pomp and circumstance, but also a lot of hard-nosed commercial work.

Both sides are keen to see more trade, and the UK in particular wants to encourage Chinese investment here.

Before any of the business gets under way there has been some news that will affect the atmosphere of President Xi's visit. We have had new data for China's economic growth in the third quarter of the year.

And it came very close to what was expected. According to the official figures China's economy grew by 6.9% compared with a year earlier. That's just below 7% for each of the first two quarters, and significantly down from the 10% average of the previous three decades.

The figures feed into what is arguably the biggest global economic issue of the moment - will China's growth slowdown be a smooth or bumpy ride? Or as it is often put - a hard or soft landing?

That there is a slowdown is beyond doubt, and in principle, as long as we do get the soft landing, it's generally seen as welcome.

China's economy is not contracting, instead the rate of growth is slowing

For three decades China's annual economic growth averaged 10%. Since 2010 it has slowed. Last year's figure was 7.4%, and it's generally accepted this year will be slower, followed by a further deceleration in 2016.

Yes, these are Chinese official figures whose reliability is widely criticised. Willem Buiter, chief economist at the giant financial firm Citigroup has suggested this year's true figure could be less than 4%. Danny Gabay of Fathom Consulting told BBC Radio 4's Today programme that it's more like 3%. He says China is already into a hard landing and there's a financial crisis on the way.

There are plenty who don't think it's that bad. But there is no real doubt that growth is slowing, perhaps by a good deal more than those official figures suggest.

Changing forces

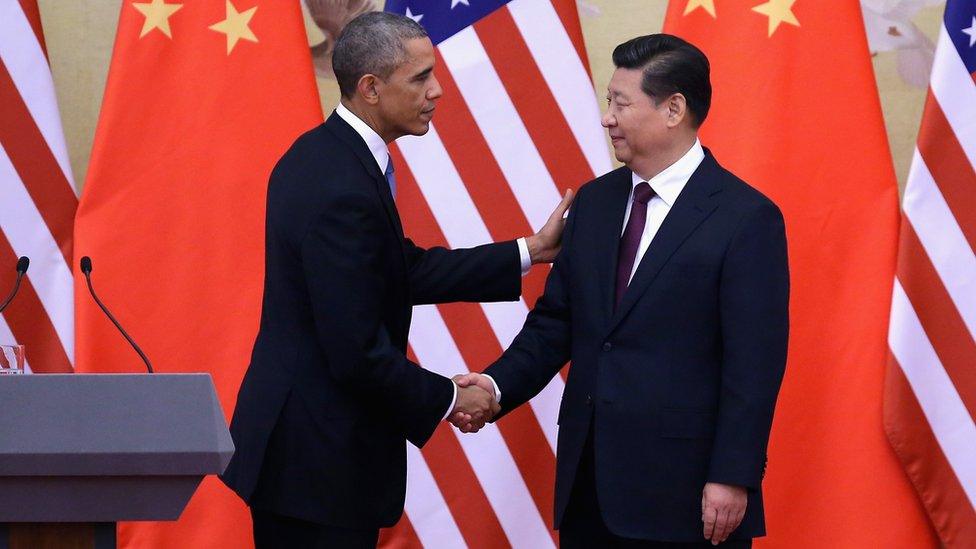

Meanwhile, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, wants to deepen the UK's commercial relationship with China.

Chancellor George Osborne visited China last month to try to boost business ties

Back in 2013 he took steps to encourage trading of the Chinese currency in London.

More recently, while in China, he told the BBC he wants the country to become Britain's second-biggest export market within 10 years. It's currently sixth.

Is that wise, you might ask? If China is slowing perhaps British exporters have missed the boat if they have not already established themselves there.

And will China be such an important source of business for British financial services?

Well, it may be slowing but it is continuing to grow. The International Monetary Fund projects growth of more than 6% up to 2019.

As China is either the largest, or second largest, economy on the planet, depending on how you convert national figures into dollars (or some other currency), it means China growing at more than 6% would contribute more growth to the global economy than any other country.

In fact China alone growing at 6% would mean global economic growth of more than 1%. On the basis of IMF projections for growth over the next few years, no other country comes close.

Even if you take sides with the statistical sceptics and take a lower figure for China's growth outlook, it still looks like an important business opportunity.

It's true some countries are already feeling the pinch from China's slowdown.

Producers of industrial commodities - energy and metals - are especially exposed. China's slowdown has undermined demand for their exports, and prices have fallen dramatically.

Not that Britain has been completely immune to this kind of problem.

The crisis and the job losses at the SSI steel plant in Redcar - and more expected at Tata Steel operations in Scunthorpe and Lanarkshire - have been blamed in part on cheaper Chinese steel sales and the fall in global steel prices

China is at the heart of the global economy

But China is not just slowing. It's trying to change the driving forces behind its expanding economy.

The aim for China's leaders is to shift from an economy driven by exports and very high levels of investment. The focus it's shifting away from - industry and big construction projects - is the kind of business that is hungry for these industrial commodities.

Instead the Chinese authorities want an economy that's increasingly driven by Chinese consumers.

So perhaps that will open up new types of opportunity.

China is the biggest overseas market for UK-built cars

Foreign Office economists have looked at where the gains might lie for British industry if China opens its economy up., external

The report suggested that cars, pharmaceuticals, and financial and business services have a lot to gain.

That certainly makes sense in terms of sectors you would expect to experience growing demand as a country's economy develops. As Chinese businesses become more sophisticated they are likely to need more specialist services, an area where Britain is strong.

More prosperous people will want more medicines, and of course more cars.

The UK's Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders said (in February): "China is the largest single market for British-built cars after the UK".

The manufacturers are not British-owned, but they do make cars in the UK and sell them abroad.

China still has a long way to go to catch up with the developed world in terms of average living standards.

Even if the whole economy is arguably the biggest of all in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), it is far behind in GDP per person, which is a rough and ready indicator of prosperity.

China's GDP per capita is just over a third of the UK's, and a quarter of the US figure. But the gap is closing.

Slowdown or not, China's economy is increasingly one of the biggest games in town, even if it's not the only one.

- Published14 October 2015

- Published27 September 2015

- Published13 September 2015

- Published1 September 2015