Britain's steel industry: What's going wrong?

- Published

Thousands of jobs in the industry are at risk

Over the past few months, one part of the UK economy, the steel industry, has been grabbing the news headlines, but for all the wrong reasons.

The announcement by India's Tata Steel that it plans to sell its UK steel business, putting thousands of jobs at risk, is the latest blow to an industry which has seen a succession of job cuts.

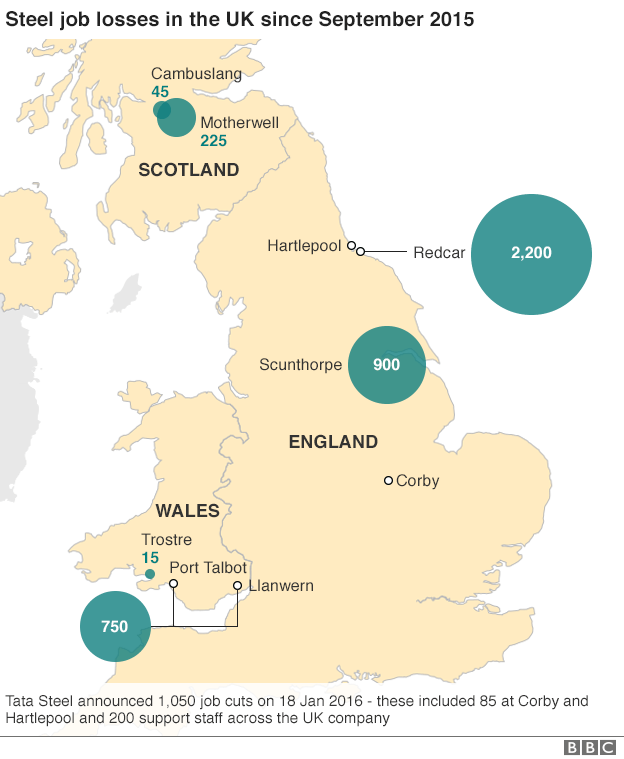

At the start of this year, Tata, which currently employs 15,000 in the UK, announced plans for 1,050 job cuts, on top of the 1,200 it axed in October 2015 and the 720 it cut last summer.

Other firms have played their part in what amounts to an industry-wide cull. In October, Thailand's SSI announced it was closing down its Redcar works with the loss of 2,200 jobs, then parts of Caparo Industries' steel operations went into administration putting 1,700 jobs potentially at risk.

The steel industry says it has been hit by a combination of factors: high UK energy prices, the extra cost of climate change policies, and competition from China - there have been allegations that Chinese steel is being sold in the UK at unrealistically low prices.

So what's the truth of it all - just why are significant parts of Britain's steel industry in such trouble?

What's behind the current crisis?

Demand for steel worldwide has not returned to the levels seen before the financial crisis. As many countries, and particularly China, are seeing weak growth, global demand will remain sluggish, external - falling 1.7% in 2015 and up by just 0.7% this year.

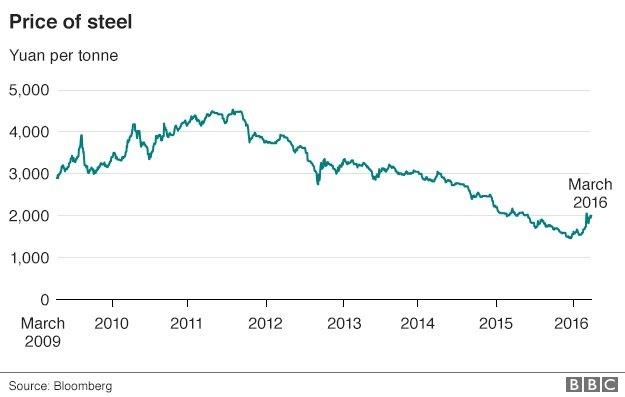

Global steel prices have fallen sharply. Meanwhile, China's own economic slowdown has led its producers to look for export markets as their home demand stalls.

As a result, UK imports of Chinese steel have increased dramatically. In 2014 the UK imported 687,000 tonnes of steel from China, up from 303,000 tonnes in 2013.

It is true that the UK's steel imports from the rest of the EU are much higher than this, they were 4.7 million tonnes in 2014, but crucially China is selling its steel at much lower prices.

Steel imports into the UK from the rest of the EU cost on average 897 euros a tonne in 2014, while Chinese steel imports were just 583 euros a tonne, says the EU's statistics agency, Eurostat. This has led to accusations that China is selling at unfairly low prices.

High UK energy costs for energy-intensive businesses like steel production are also a factor, says the industry, added to by the extra cost of climate change policies. And government policies to compensate producers for these extra costs have been too slow, says the industry body UK Steel.

EU rules also restrict how much support governments can give to particular industries. Member states may not use public funds to rescue failing steelmakers. However, EU countries are allowed to boost steel firms' global competitiveness - for instance by funding research and development or helping with high energy bills.

How many steel jobs could go?

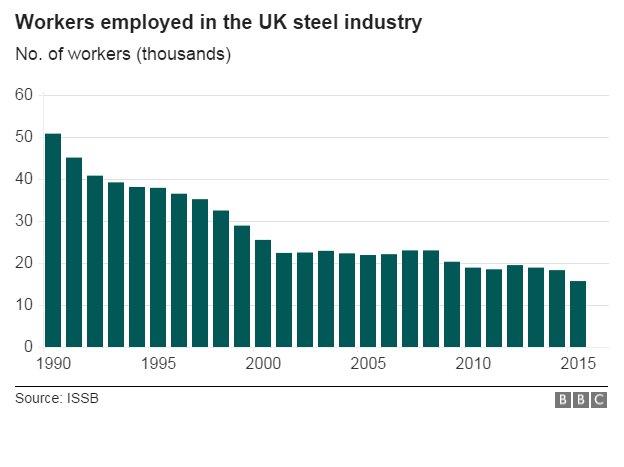

Almost 18,000 people are employed in the steel sector, and some experts say that up to one in four of these jobs could be at risk over the next few years.

The confirmation earlier this year by Tata of 1,050 job losses comes on top of the 1,200 jobs it axed last October and the 720 jobs it cut in July.

Also in October, the country's second-largest steel producer, Thai firm SSI, said its Redcar works on Teesside, would go into liquidation with the loss of 2,200 jobs.

At the same time, Caparo Industries went into partial administration, putting 1,700 jobs at potential risk.

Can we really just blame China?

The industry blames cheap Chinese imports for a collapse in steel prices.

Chinese steel producers are accused of "dumping" exports in the EU

It is certainly true that China's dramatic economic growth since liberalisation started in 1979 has been one of the key drivers in the global steel market.

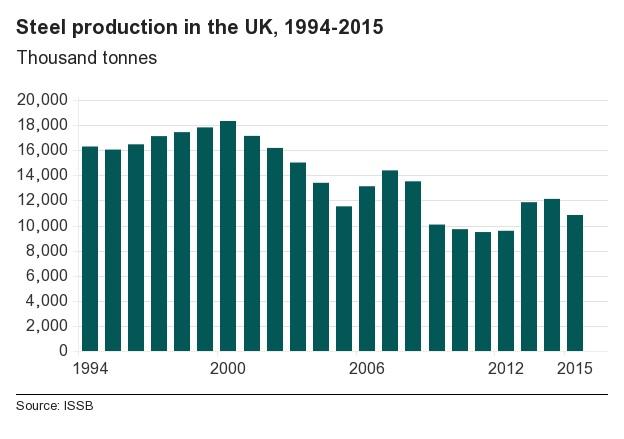

It is now the world's biggest steel producer, accounting for around 822 million tonnes a year. The UK, which produces almost 12 million tonnes a year, is a minor player in terms of absolute output, but has sought to specialise in high-quality, high-value steel products.

With China's market slowing, their producers have been looking for export markets, such as the EU.

This has led to accusations of unfair competition, that Chinese producers are "dumping" steel products on overseas markets - that is not just selling them cheaply, taking advantage of their lower production costs, but actually selling them at a loss.

In 2015, the EU imposed anti-dumping duties for six months on some steel imports from China and Taiwan. The EU and China have already clashed over the alleged dumping of products such as wine, solar panel and steel pipes.

How important is steel for Britain?

Steel itself is vital for just about everything we use. Whether it is buildings, clothes, chemical, cars, lamps or drinks cans - all depend on it at some point.

The industry has seen significant automation and computerisation and is not as labour-intensive as it used to be.

About 18,000 people are directly employed in the steel industry. With a total UK workforce of 31 million this is just one in 1,700 jobs.

However, if the industry was to shrink further there will be an impact in other allied sectors - steel processors, distributors, scrap metal dealers, metal traders and other metal product manufacturers.

Many argue that this is not just a crisis for the steel sector, but one affecting UK manufacturing in general, which accounts for roughly 10% of UK economic output.

So what can the UK do?

The industry is clear what it needs: lower business rates, a relaxation of carbon emissions targets for heavy manufacturers, more compensation for high energy prices, and a commitment that British steel is used in major construction projects.

The government held a steel summit in Rotherham last October to discuss what could be done.

The government is under pressure to do more to support the sector

It says it has already taken "clear action" to help the industry, "through cutting energy costs, taking action on imports, government procurement and EU emissions regulations, meeting key steel industry asks."

But UK Steel says it still needs to do more.

"We need much further action taking place to tackle the imports, the flood of Chinese steel into the UK and the European economy. We need to see government and the European Commission tackling that head on and quickly," says Gareth Stace, director of UK Steel.

"Ministers can also do more by reforming business rates to exclude some of the penalties steel companies and others face if they invest in plant and machinery," says Terry Scuoler, chief executive of EEF, the manufacturers' organisation.

"Alongside this, the UK has one of the highest electricity costs for the energy intensive industries in Europe because of hindering domestic policy. We need to see a level playing field with our European competitors to ensure a positive future for the steel sector," he says.

Does the steel industry have a future in the UK?

Business Minister, Anna Soubry, said on Radio 4's Today programme that the government was determined to ensure that Port Talbot continues to make steel.

The world faces a huge oversupply of steel - currently only two-thirds of the steel being produced is actually being used

Despite this, some gloomily predict that steel production itself - as opposed to specialised rolling and milling of already-manufactured steel - faces a bleak future in the UK, and that the number employed in the industry will continue to fall, possibly to as low as 13,000 within a few years.

The world faces a huge oversupply of steel - currently only two-thirds of the steel being produced is actually being used.

Tata itself says that "trading conditions in the UK and Europe have rapidly deteriorated" recently, due to the global oversupply of steel, a "significant" increase exports into Europe, high manufacturing costs, continued weakness in UK demand for steel and a volatile currency.

Energy intensive businesses, like steelmakers, also face higher electricity prices, external in the UK than they do in many of the Britain's European neighbours - and the industry has been calling for urgent action on this.

- Published18 January 2016

- Published20 October 2015

- Published20 October 2015

- Published20 October 2015

- Published19 October 2015

- Published17 October 2015

- Published12 October 2015