Tax credits, pensions and the generation game

- Published

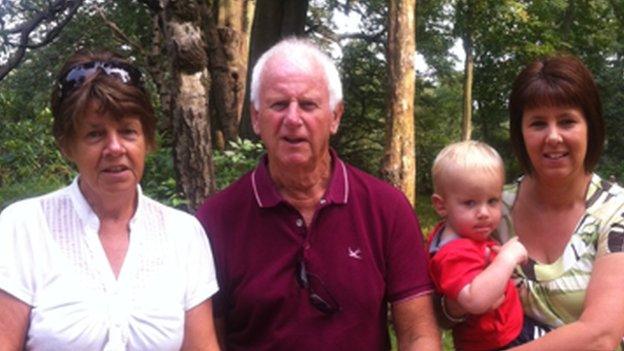

Leza Brumbill (right) says her parents help with holiday costs too

When it comes to pocket money and treats for her three children, cash-strapped single mum Leza Brumbill has to turn to her parents for financial help.

The 44-year-old, who lives near Southampton, also says holidays would be out of reach were it not for the support of her father, Alan, and mother, Sandra.

Now Ms Brumbill, who works 24 hours a week as a school science technician, faces the loss of hundreds of pounds of income from tax credits under government cuts.

"Surely there are other groups of people to look to [for cuts] before single parents and working families," she says.

The focus, according to some commentators, should be on her parents' generation, whose pensions have been protected from any deficit reducing cuts.

Her mum, Sandra Williams, 69, says that among their retired friends "not everyone is on a high income, but many of them are helping their grandchildren with money".

Their daughter is sometimes in tears on the phone when talking about her finances, according to retired draughtsman Alan, 74.

"We appreciate the fact that we are lucky," he says.

It was hard work, not luck, which meant they held down good jobs and saved during their working lives.

But some argue that it is lucky that their generation will benefit from an inflation-busting rise in the state pension, their benefits will be untouched for five years, and their workplace pensions were more generous than for today's young workers.

Pension pennies

The triple-lock - a government promise for the next five years - means the state pension rises each April to match the highest of inflation, earnings, or 2.5%. In April 2016, that is likely to mean a rise in the state pension of 2.9%.

Conservative activist Tim Montgomerie described the pledge as "ludicrous" as it came at the same time as tax credit cuts to low-income families.

Jonathan Isaby, chief executive of the TaxPayers' Alliance, says that "intergenerational unfairness" is simply the result of a government's calculation that older people go out to vote, not the realities of economics and life expectancy.

He says pensions should not simply be seen as a delayed payout of tax contributions made during people's working lives.

"The taxes current pensioners have paid have not been put aside for them in retirement," he says in a blog, arguing that the money was used to pay fewer pensions to the last generation who did not live for as long in retirement.

"Now the current taxpayers have to fork out for the longer, far more generous retirements enjoyed by today's pensioners," he says.

Arguably, the most significant contribution to the debate came from the widely respected and independent economist Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

In a recent speech, he said that the triple-lock policy "needs to end".

"At some point it will prove to be prohibitively expensive," he said.

He said that pensioners' incomes have continued to rise after the recession whereas working-age households have seen income fall.

There has been "a remarkable transformation", he says - about 30 years ago, pensioners were at least three times as likely to be poor as non-pensioners. Now they are less likely.

His headline conclusion is that pensioners have higher average incomes than working-age households, once housing costs and family make-up are taken into account.

Tax credits debate

Generational differences in income and exposure to cuts is central to the tax credits debate.

Chancellor George Osborne is mulling over "transitional help" for families hit by his proposed cuts to tax credits, after a defeat in the Lords.

It is perhaps no surprise that, on Thursday, the Resolution Foundation said that one way of preventing 3.3 million families losing an average of £1,300 from tax credit income next year was to cancel the tax credit cuts and find the savings from changing the triple-lock and reforming pension tax relief instead.

The Foundation, which lobbies for those on low incomes, suggested five areas, external where the £3.6bn of savings currently earmarked from tax credit cuts could come from instead.

Among the quintet was the idea of scaling back the "over-indexation" above earnings of the state pension from the last five years, by limiting pension rises in this Parliament. That, the Foundation says, would save £6bn by 2020.

What happens next?

However sound the economics of getting rid of the triple-lock to spread the burden of cuts across all generations, the politics do not add up.

That is the view of Frank Field, Labour chairman of the Work and Pensions Committee, who says alteration to pensioner protection will not happen in this Parliament.

"It is tempting to put aside the triple-lock," he said at Thursday's Resolution Foundation gathering.

"But I do not believe that is possible politics in the near future."

In January, Prime Minister David Cameron said: "People who have worked hard, who have done the right thing, who have provided for their families, they should then know they will get a decent state pension, and they don't have to worry about it lagging behind prices or earnings, and I think that's the right choice for the country."

There is nothing to suggest he has changed his mind.

Early inheritance

Many pensioners will argue that the extra £3.36 a week of state pension to be paid next April is hardly a gift of immense riches.

They will also say that, however much they are protected from welfare cuts, they feel obliged to help their children with housing costs, or grandchildren with higher education fees.

In practice, if not in theory, they are passing on the benefit they get from pension protection to younger generations anyway.

Whether that is welcome or sustainable is debatable, and it may even lead to a new layer of financial dependency.

Gill Cuthbertson, a single mother of a boy with Down's Syndrome, relies at times on money borrowed from her parents.

"I don't want to ask my parents for any money. I shouldn't have to ask them. I'm 45," says the NHS worker from East Yorkshire.

Were her tax credits to be slashed, she says she might have to ask for a lot more.

"If it came down to it, I could end up living back with my parents," she says.