Smallpox general in US university row

- Published

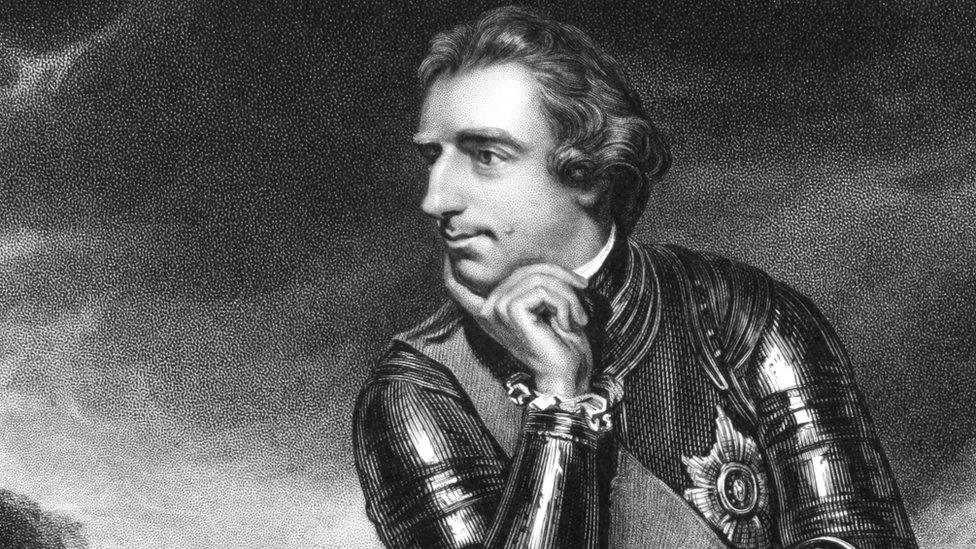

Lord Jeffery Amherst - the first Lord Jeff - suggested spreading smallpox among Native Americans

An 18th Century British general is at the centre of a US university dispute about racism and biological warfare.

Amherst College, a top-ranking liberal arts college in Massachusetts, is facing a campaign by students to scrap its "Lord Jeff" mascot.

The "Lord Jeff" in question is Lord Jeffery Amherst, the colonial soldier after whom the college and the town of Amherst are named.

Many universities have had to reconsider associations with dubious historical figures, but the Lord Jeff case is more extreme than most.

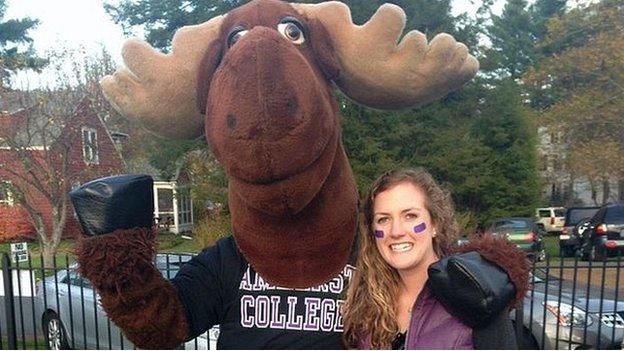

Virginia Hassell with a moose as an alternative mascot

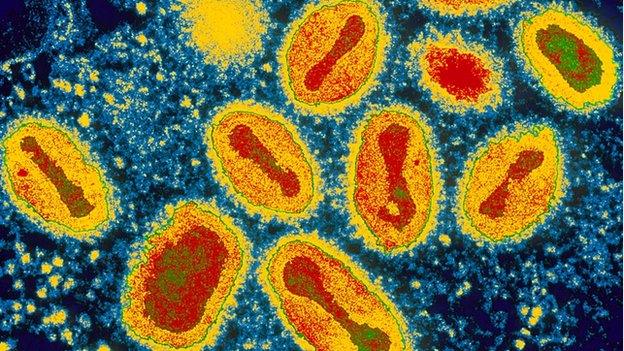

Lord Amherst, a governor-general in pre-independence America in the 1760s, is accused of advocating the wiping out of Native Americans by deliberately giving them smallpox, by means of a gift of infected blankets.

In the university's own account, it quotes the general as writing to an officer: "Could it not be contrived to send the Small Pox among those disaffected tribes of Indians?"

More stories from the BBC's Knowledge economy series, external looking at education from a global perspective and how to get in touch

He spelled out the plan later: "You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race."

Lord Amherst, who was born and died in Sevenoaks in Kent, was also sympathetic to the idea of hunting down the local Native American population with dogs.

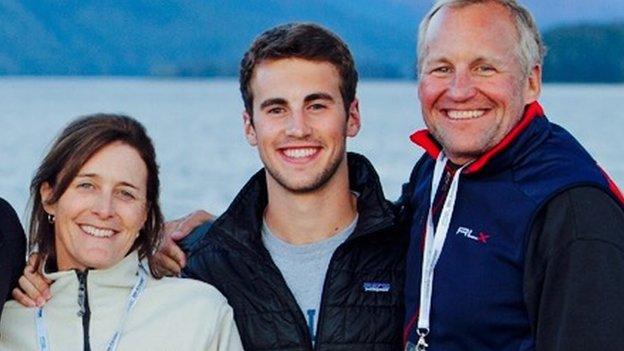

Thomas Sommers (centre) wants more attention paid to the views of former students such as his parents

Amherst College's reputation is based on the cultivation of the arts, with links to poets such as Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson.

The associations with ethnic cleansing are becoming increasingly awkward.

Students at the college are campaigning to scrap the mascot as part of wider concerns about being inclusive and tackling racism. There have been sit-ins and a vote on the mascot is being held this week.

Virginia Hassell is supporting a student campaign to end the use of the Lord Jeffery mascot.

She says the mascot's associations are "racist and offensive" and it is not how the university should be represented and it shouldn't be appearing on clothing associated with the college.

As campuses become more diverse in their intake, she says there is going to be more scrutiny of such symbols.

The dispute at Amherst comes amidst a wave of protests and arguments over race and identity in US universities.

Smallpox virus: Lord Jeffery Amherst wanted to spread it with infected blankets

Ms Hassell, who has been in talks with college authorities, says she is confident that the mascot will be changed, but not as quickly as campaigners might want.

"I'm feeling optimistic about the direction we're heading in right now. The conversation has shifted from, 'Are we going to change the mascot?' to 'What are we going to change it to?'"

And there are students opposed to losing the Lord Jeff mascot.

Part of an Amherst student leaflet ahead of a vote over the mascot

Thomas Sommers says he is sensitive to the concerns about Lord Amherst's "atrocious" behaviour, but he doesn't associate the mascot with the 18th Century general.

"Personally, the way I see it is that the mascot is just an embodiment of Amherst College. It's a mascot and nothing more.

"Like the name of the college or the town of Amherst, when I think about the name I don't think about Lord Jeffery Amherst. And when I think about the mascot I don't think about the historical figure."

Both his parents went to Amherst and he says changing the mascot would mean losing a tradition that links present and past students.

Any decision on scrapping the mascot should take into account the views of such alumni, he says.

There is a campaign to change Harvard Law School's seal because of links to slavery

The college remains non-committal: "There are understandably mixed views about changing it," says a statement.

And it says that "people at Amherst will continue to think about the issues in all their complexity".

The college's board of trustees is expected to examine the issue early next year.

But both Thomas Sommers and Virginia Hassell, on either side of the argument, believe a change is ultimately likely.

It's part of a wider pattern of controversies over emblems and the legacy of universities' links with the past. Should universities change symbols to reflect changed attitudes? Or should they keep them in place and accept that in the past people had views which now seem repellent?

Campaigners in the US have linked their protest to students in South Africa

At Harvard Law School there is a growing campaign to change the school's seal, which includes the family crest of an 18th Century donor Isaac Royall.

The wealth that allowed him to leave land to Harvard was drawn from being a particularly brutal slave-owner and slave-dealer who, it's claimed, burned slaves to death in reprisal for a revolt.

Opponents have argued that altering the emblem would only be a cosmetic change and wouldn't address the issue of how or whether an institution should be held accountable for its past.

But the campaigners argue that the school should rid itself of such visible associations with slavery and have adopted the slogan Royall Must Fall.

The slogan links the campaign to the Rhodes Must Fall student protest in South Africa, which earlier this year saw a colonial-era statue of Cecil Rhodes being attacked and ultimately removed from the University of Cape Town.

The statue, which had been on the campus since the 1930s, became the focus of student protesters who saw it as a surviving symbol of an era of discrimination against the black majority.

Academic and social commentator Frank Furedi says there is a "powerful impulse" on US campuses at the moment to question "traditional conventions, rituals and symbols".

He says it is part of the "ascendancy of identity politics" on campus, where politics are based around issues such as race, gender, religion or sexuality.

With such an approach to politics, he says, students are seeking symbolic ways to assert their identity.

"Consequently anything can become an object of protest.

"Increasingly identity in the present is being affirmed through insisting on the erasure of the traditions of the past."

Prof Furedi predicts: "There is little doubt that this trend will intensify."