Online chatting at work gets the thumbs up from bosses

- Published

Chatting at work is one thing, but could chatting about work online make us more productive?

Fancy being Facebook friends with your boss? Or being allowed to Snapchat your colleagues during office hours?

Well, this kind of office-based social networking is growing in popularity as a way of escaping the tyranny of corporate email.

Businesses wanting to streamline internal communications are turning to chat apps like Chatter, Slack and Yammer, as well as more established platforms like Facebook.

The market for enterprise social software, as it's called, will be worth more than $8bn (£5.3bn) by 2019, up from about $5bn now, according to research firm Markets and Markets.

Of course, we've had company intranets for almost 20 years, but it's the mobile friendly nature of many messaging apps that is shaking up this space.

In January 2015, Facebook unveiled its new business networking platform, Facebook at Work and has just launched an associated chat app, Work Chat.

Most of us are used to social media in our private lives, but what about for work?

The social networking giant, with its 1.5 billion users, seems to want to dominate the corporate market, as well as the private sphere.

Facebook has signed up around 300 companies of varying sizes, including Heineken, Lagardere and Hootsuite.

'Collaborative culture'

By far the largest deal it's struck so far is with Royal Bank of Scotland, which announced in late October that following a successful pilot programme it will be rolling out Facebook at Work to all 100,000 employees in 2016.

But why?

Kevin Hanley, director of design at RBS says it's all about facilitating collaboration between different arms of the business. Facebook at Work is "a key component in driving a more transparent, engaged, collaborative, culture," he says.

Sentiments echoed by Julien Codorniou, Facebook's director of global platform partnerships, who says the platform is more than just a means of communicating, it's a tool that drives productivity.

"We fundamentally believe that a connected workplace is a more productive workplace," he says. "We want to connect three billion employees worldwide. All you need is a phone.

"We are giving everyone a voice."

Facebook at Work functions in the same way as personal Facebook, and Mr Hanley says the familiarity explains its success at RBS.

Facebook is aiming to consign work emails to the dustbin of history

"We're finding there is no steep learning curve or training required. That means the adoption rate is much higher than previous attempts at doing something similar," he tells the BBC.

Add in the benefits of its mobile app, which frees employees from desk-based applications, and RBS has found the tool to be "immediately useable".

'Finger on the pulse'

One of the most compelling reasons to try these new ways of working is to find an efficient alternative to the deluge of corporate emails, which, let's face it, can sometimes be overwhelming.

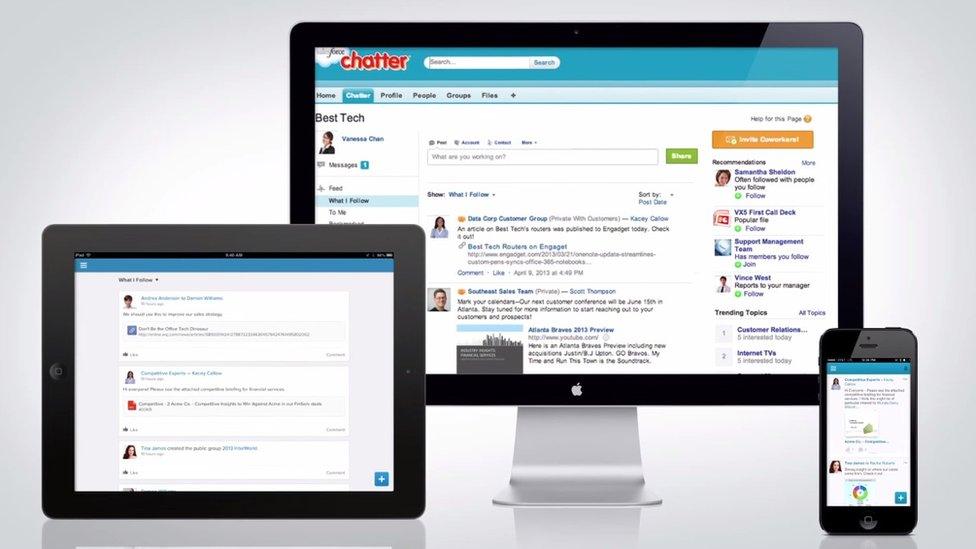

Accounting software firm Sage implemented online communications portal Chatter into its business in April 2015.

If everyone can join in the conversation will it make us more productive?

Sandra Campopiano, the firm's chief people officer, says 9,000 topics have already been moved off email into "direct, snappy messages, or open, engaging groups and forums."

"We want our people to use channels that feel natural to them and which help them to be collaborative," she says.

"So social has to be one of the options, particularly in a tech company where so many of our colleagues are digital by nature."

Andy Jankowski, founder of Enterprise Strategies, a corporate communications firm, explains that the value of these new enterprise social networks (ESNs) lies in this ability to make communications more natural and conversational.

Salesforce's Chatter platform provides workers with secure social networking on any device

"They allow employees to comment, ask clarifying questions or share experiences in support of the messages being communicated," he says.

"Communicating via an internal social network enables you to have a finger on the pulse of the organisation."

The death of email?

But do these new ways of communicating really spell the end for the work email?

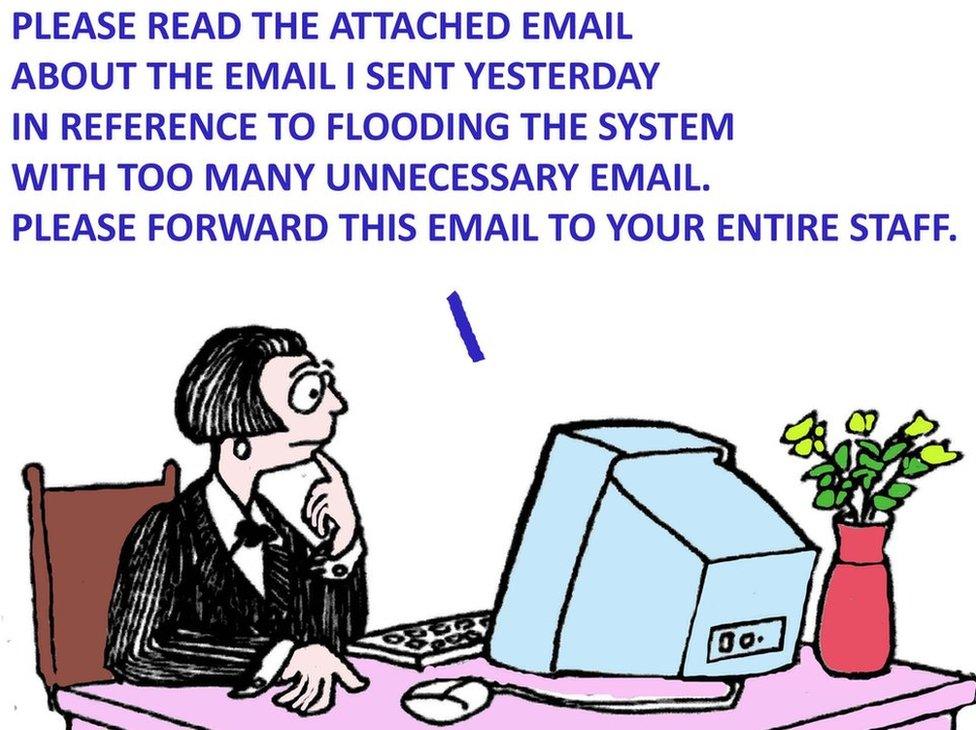

Critics of the venerable platform say it is essentially a one-way method of communication. Senders often have no effective way of knowing if the contents of their messages are relevant or understood. And recipients waste time sifting through emails they don't need to see.

"Email overload is a common phenomenon in many corporations, resulting in employees simply not reading all that they receive," says Mr Jankowski.

Are we drowning in a flood of unnecessary corporate emails?

"This creates an environment where employees are often out of the loop because of the emails they have not read."

Move conversations off email onto a social network where people can opt in or out and you have a fast-moving, visible means of sharing information and solving problems, they argue.

While Mr Jankowski thinks email is still the best way to communicate with one person or a small group, he agrees that the end of the companywide broadcast email may be nigh.

Ms Campopiano says "we may eventually see [email] die out, just like the fax."

A waste of time?

But surely receiving endless message alerts and conversation updates can become highly distracting in the work environment and lead to lower, not higher, productivity?

Won't we all be swapping cat videos?

Quite the reverse, argue Mr Hanley and Ms Campopiano: the ability to opt-out of irrelevant conversations actually frees up time.

Could social media at work help us collaborate more effectively, the way ants do?

And Mr Codorniou says that while employees access Facebook at Work up to 50 times a day, the conversations are all about work.

In fact, Mr Jankowski believes that the data harvested by all this social network activity could prove very useful for businesses.

"We already use social network analysis with social media to make marketing decisions," he says. "What if we could harness the collective brainpower of all employees to make better business decisions based on conversations and insights being shared across our internal social network?"

Security concerns

One issue that may make firms think twice about adopting social media-style apps for internal communications, however, is data security - where, and how securely, is your ESN provider storing all these potentially sensitive corporate conversations?

The EU's rescinding of the Safe Harbour agreement means firms can't assume US-based service providers are offering adequate privacy protections.

If it's in the US, would you be happy for the US government to get its hands on them, invoking the Patriot Act?

That's something to chat about - offline probably.