Why do many Americans mistrust the Federal Reserve?

- Published

Many Americans distrust central government including the Federal Reserve

There is little agreement in the United States at the moment, but when it comes to the Federal Reserve, many Americans feel their central bank is broken, pointless or at worst bad for the country.

Just a third of Americans felt the Fed was doing a good or excellent job, according to the last Gallup, external poll to check on the bank's popularity. The only US federal agency with a consistently lower approval rating was the IRS, the Internal Revenue Service or tax collector.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have taken swipes at the Fed.

Republicans chastise the bank for its prolonged policy of low interest rates. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump accused the Fed of keeping interest rates low to protect President Obama.

Democrats, meanwhile criticise attempts to raise rates.

In August, activists from the liberal-leaning Fed Up campaign protested outside a Fed meeting in support of low interest rate, saying that they say help low income families.

The Fed has taken hits from the right and the left

"There is no question that [the Fed's] reputation has taken a hit from the extreme left and the extreme right," says Donald Kohn, a Federal Reserve governor from 2002-2010.

Alan Greenspan's tenure

It wasn't always like this though. Under the tenure of Alan Greenspan - who served as the Fed's chairman from 1987 to 2006 - many felt the central bank was a positive force for the economy.

During the 1990s US unemployment reached 4% while inflation remained low.

Mr Greenspan's approval rating was 72% when he left the Fed. According to Allan Meltzer, author of The History of the Federal Reserve, Mr Greenspan's tenure was "the best period in Federal Reserve history".

He wasn't without critics.

President George HW Bush and Republican members of Congress criticised Mr Greenspan and the Fed for raising interest rate in 1994. President Bush even accused Mr Greenspan's policy of costing him the election against Bill Clinton.

Former Fed chair Alan Greenspan left the central bank with a 72% approval rating

Experts say many of the policies that helped the economy grow under President Clinton can really be credited to Mr Greenspan.

However, since the financial crisis politicians and economists have pointed to the loose monetary policies he championed as a factor leading to the crash.

Mr Greenspan also believed it was the Fed's duty to "to serve as a source of liquidity to support the economic and financial system."

This policy was a precursor to the 2008 bank bailouts.

Bailing out the banks

According Mr Meltzer, the Fed's decision to bailout the banks has shaped many Americans' current distrust of the central banking system more than the prolonged period of low interest rates.

"The public doesn't think the government should be in the business of bailing out banks," he says.

Senator Elizabeth Warren has been an outspoken critic of Wall Street and its relationship with the Fed

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have criticised the bailout, saying it helped banks at the expense of the American tax payer.

"If big financial institutions know they can get cheap cash from the Fed in a crisis, they have less incentive to manage their risks carefully," says Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat who has built a reputation for challenging Wall Street.

Supporters of the Fed's bailout action argue it was necessary and see the anger it created as a symptom of the suspicion that already existed.

"The perception that expanding the discount window bailed out the big banks at the expense of Main Street comes from a long history of distrust a lot of Americans have in New York and Washington," says Mr Kohn.

Disliked from the start

America's distaste for central banks is not new. The country's founders fought over whether a central bank was necessary.

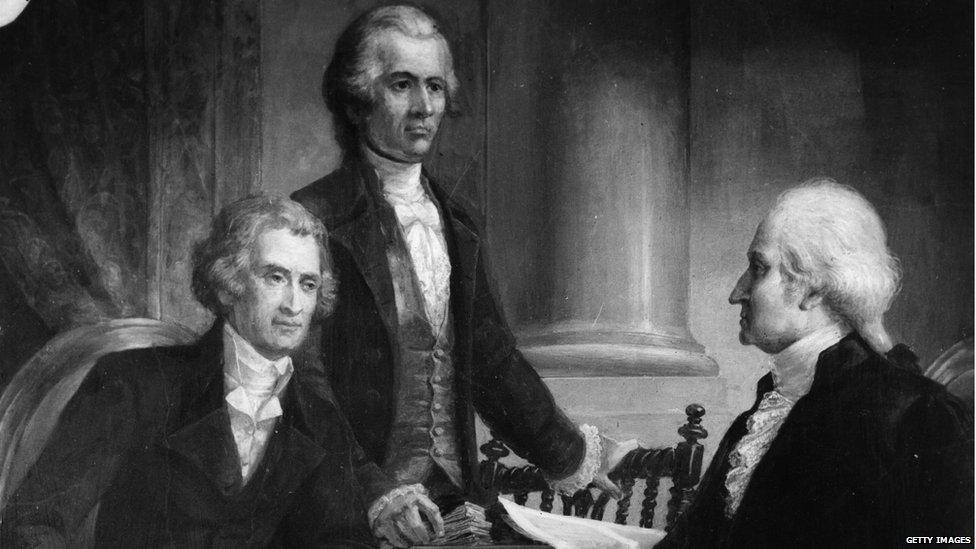

George Washington with his advisors Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson

Alexander Hamilton - America's first secretary of the treasury - urged the creation of an institution to help manage a single currency for the new country and stabilize the states' credit.

Opponents, including Thomas Jefferson - the third president of the US - saw the central bank as an unnecessary consolidation of power.

They argued it benefited investors, banks and businesses above the wider population.

The US had two central banks before the Fed. Both only lasted 20 years.

President Andrew Jackson, who opposed renewing the charter of the second US central bank, famously referred to it as "a den of vipers and thieves".

Many Americans are sceptical of big government in Washington DC

The Federal Reserve itself was founded in 1913 in response to several financial crises.

Despite surviving 102 years the bank has been regularly flogged for failing to prevent financial crises, including the Great Recession.

The recent criticism of the Fed is not that different from the criticism central banks received at the country's founding - favouring bankers and too much centralisation of power.

"The US already had a strong culture of freedom and it sees central banks as an opponent of freedom and a source of centralization that many dislike," says Mr Meltzer.

Politicians question the Fed's relationship with Wall Street

This time around

To raise interest rates this time around the Fed will use a new method that has been criticised as benefiting banks.

Traditionally, the Fed increases the amount of securities it sells to banks. This forces banks to charge higher interest rates to bring in revenue to pay for the securities they are buying.

This time, the Fed will pay banks a higher interest rate for storing reserves at the central bank. If banks make more money holding reserves at the Fed they have no incentive to charge low interest rates.

Fed chair Janet Yellen is often the focus of critics who dislike the central bank

Critics say the Fed should not be in the business of funding banks' profits.

Becoming more likable

It is difficult, given America's history, to say what might make the Fed more appealing.

In 2013, 74% of American supported auditing the Fed's decisions and finances. A new bill to increase the amount the Fed is already audited has been proposed by Republican Senator Rand Paul.

At this point the only thing that might improve the Fed's reputation is time and an improving economy.

But regardless of whether the Fed gets the decision right on Wednesday the critics will still be out there.

- Published9 December 2015

- Published9 December 2015