Real-life Sherlock Holmes: How to earn a living as a private detective

- Published

In the BBC's adaptation of Sherlock Holmes the eponymous hero relies more on wit than on tech, but would that be true in real life?

In a smart square a few hundred metres from 221B Baker Street, the most famous address in detective fiction, stands an intriguing shop. In the window is an array of curious gadgets and hi-tech equipment that wouldn't look out of place on a film set.

Spymaster stocks everything the budding undercover operator might want, from night vision goggles, to a pen that can scan documents, and a box of tissues concealing a video camera. It's the kind of shop that could have made Holmes and Watson's lives a whole lot easier, if they weren't so wedded to relying on pure wit and running down London's cobbled streets apace.

Spymaster, it is probably fair to say, doesn't equip many of the staff of MI5 and MI6. Instead its business comes from bodyguards needing discreet stab vests and from suspicious business partners, as well as people who want to check up on relatives in care homes.

And private detectives.

"They start with a tracking device and as time goes on, and it's working for them, they add to it," says Julia Wing, the shop's director.

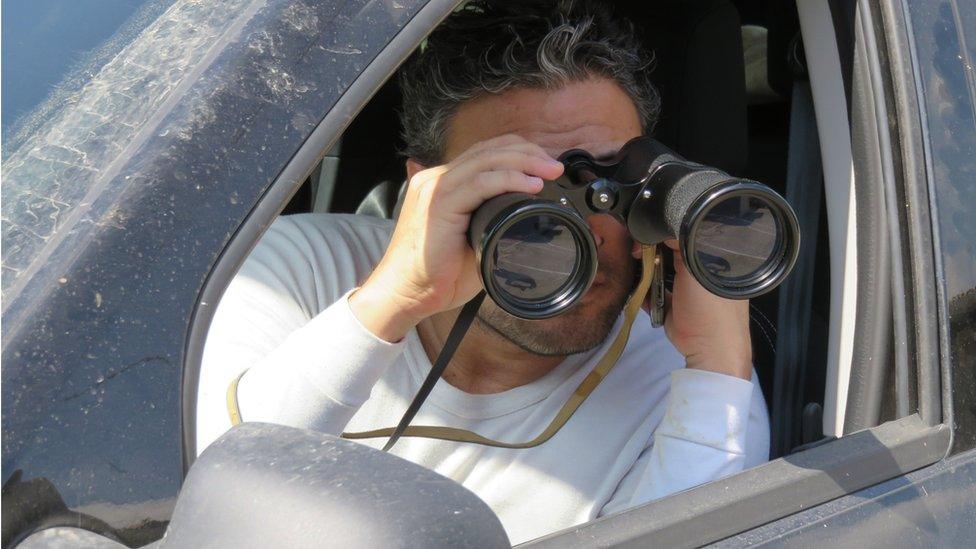

The stake out is not what it used to be

In some ways the modern private detective's life is much easier than in Conan Doyle's day. For just a few hundred pounds you can purchase a piece of GPS equipment that you plant on a car. You can then track automatically whether it's travelling beyond a preset perimeter, even which house it is parked outside. That saves a lot of time sitting and watching a target with your collar turned up against the rain.

"It's a lot of man hours to follow someone. This does the job for you," says Ms Wing.

Elementary

The Law Society Gazette estimates that there are 10,000 private investigators in the UK.

James Harrison-Griffiths is one such individual.

Working from offices in Brentwood, Essex, Mr Harrison-Griffiths' company, Aitch-Gee Investigations, offers a range of detective services including surveillance, tracing missing people, asset searches and personal injury and accident investigations.

His specialism is, however, something rather more macabre.

"The bulk of my work is investigating suspicious deaths. Sometimes the police conclude a victim committed suicide, but the family of the deceased isn't convinced. They come to me via a solicitor and I'll conduct my own enquiries."

This involves finding clues that may have been overlooked in the initial investigation.

"In a recent case a young man went missing after leaving a nightclub. His body was found on the bank of a canal a few hours later. The police concluded that it was suicide, but his family disputed this and I was brought in."

Mr Harrison-Griffiths reviewed the photographic evidence and saw that there were injuries that had been missed first time around.

"We put the new evidence to the police and they re-opened the case."

James Harrison-Griffiths says a detective's core skill is listening

Mr Harrison-Griffiths' work means obtaining sensitive information. But his background - 30 years as a detective inspector in charge of a murder team in the Metropolitan Police - helps him ensure he remains on the right side of the law.

"For private investigators, knowledge of the law is vital, you can't just trawl through someone's bank statements and phone records," he says.

After all, there's no point building a case if the evidence is inadmissible in court.

Aitch-Gee Investigations is a tight knit unit with two employees, Mr Harrison-Griffiths and his wife Maureen, who acts as his secretary. Like the fictional Sherlock however, he does occasionally enlist the services of an outside expert on an ad hoc basis.

"When it comes to forensics, whether it's a death or a financial investigation, you can't do it all yourself. We have contacts to do some of the analysis on our behalf."

But the core skill, as both Mr Harrison-Griffiths and Sherlock Holmes would acknowledge is not something new tech can help you with.

"One of the most important things is listening. Let the person you're talking to give you the clues. Ask them a difficult question and wait for the answer," he says.

"Don't be afraid of silence, your subject might be trying to work their way out of a tricky situation. Don't make it easy by giving them a way out."

Rewards

Private investigators typically charge around £200 an hour but some ask for more than double that depending on the demands of the particular job.

Would you spot that these glasses were secretly filming you?

Spymaster also stocks these high-tech safes disguised as cleaning products

And there's even a one man submarine, for any underwater surveillance work that turns up

Julia Wing at Spymaster says that these days, with so much technology available almost anyone can set up as a private detective, for around £1,500 to purchase the basic kit.

Paul Hawkes an industry veteran who founded his company Research Associates in 1977, agrees that new technology is changing the private detection business.

He says he did have a hairy moment earlier in his career when a Mossad agent-turned-arms dealer wanted to discuss with him some unresolved death threats. But these days he spends most of his time quietly trawling the web.

"It's a huge jigsaw puzzle," he says. "Nobody can work in the industry without a pretty good understanding of what's out there [on the internet]".

He says while privacy laws have narrowed what data you are allowed to access, the "bucketloads" of private information available freely and legally on the internet have more than made up for that. But he says it's still down to the skill of the detective to use that knowledge, develop a hypothesis and then test it rigorously.

He cites a recent case of a murder in Greece believed to involve London gang members. He was able to use social media postings to identify who was present when and where.

"It was relatively easy because of the net and knowing how it all works. [But] the [victim's] parents thought I was a magician."

A lot of his work revolves around tracing people, marital disunity and fraud.

The really big jobs get left to the established research businesses such as Kroll which have built their business around conducting in-depth investigations for corporations, central banks and governments.

For the upcoming episode of Sherlock Holmes, Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman are being relocated to the low-tech Victorian era

Although it's on a different scale, it is still essentially a case of unearthing information someone is trying to keep hidden.

"The focus is normally on tracing funds and providing evidence to back up the recovery of money or assets." says Tommy Helsby, chairman of its investigations and disputes group.

"A client might want to exploit gold in the ground in Central Asia. We make an assessment. Is the information presented to the client accurate?"

Mr Helsby says, just like for other members of his profession, there is one vital skill he needs for his work.

"You've got to be able to read people. Whether you're looking into an investment opportunity on behalf of a client or investigating a fraud, it's about analysing people and their motivations.

"That's very much what Sherlock Holmes does; the methods are different but the intellectual challenge is the same."

- Published10 December 2015

- Published24 September 2015